Best Viewed in 800x640 using Internet Explorer

Gold Mining Terminology

A diggings - as the word shows, is one of those spots

where gravel has been dug and sifted in search for the

yellow treasure. (The word placer and diggings, means

one and the same thing.)

Assay A test of ores by chemical methods to determine the amount of precious

metals they contain.

Carbon in pulp (CIP) - The name of the process by which gold and silver are

liberated from the ore. The gold and silver are dissolved in large tanks and

then adsorbed onto carbon granules

Claim monuments - A pile of rocks about three feet in diameter and two feet

high, topped with a locations stick that had the name of the mine and the

finder. Inside the pile of rock would be a tin setting forth the conditions

of the claim, so many days to do work, and measure of his land area, and time

enough to file the record at the county seat.

Float - Mineral rich ore (a rock) that had been dislodged from its source

and was moved by nature. A prospector would try to locate the source of

this rock and then stake a claim.

Placer gold, or free gold was supposedly washed into the

creeks and gullies during the alluvial age, but a placer

is sometimes formed by erosion also. The gold

generally lies thickest on bedrock and is known as

paystreak. The gravel or wash is found in depths

ranging from a few inches to three or four hundred

feet.

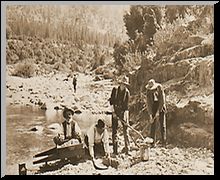

Placer Mining - A gravely sandbank, generally located in

an ancient river bed, where loose gold is usually found.

Troy ounce - system of weight employed in Great Britain

and the U.S., used for the weighing of precious metals.

The name is derived from the city of Troyes, France,

where the system originated. The troy pound is 340 g

(12 oz), and the troy ounce is the basis of apothecary

weight.

Tunnel mining at that time was done by DOUBLE STRIKING; that is one man

turned the drill and the other struck the head of it with a eight pound

hammer.

Gold Panning

|

Sluice Box

|

Hydraulic Mining

|

A deposit that is not to deep can be worked by pick and shovel, but from

ten feet to hundreds of feet deep have been worked by hydraulic pressure

since the earliest days of mining history in the West. Outfits and companies

often build immense reservoirs high up in the mountains, piping the water to

the diggings for hydraulic purposes. In hydraulic mining a strong current

of water is forced into the placer dislodging the sand and gravel, which is

caught in a sluice-box.

The sluice-box was built of plain

rough lumber like a trough with both ends left open.

Slats, or riffles, which were blocks of wood, rails,

poles, iron bars, and often sacking, matting, or hides

with the hair up, were laid crosswise on the bottom of

the sluice-box, being farther apart at the end of the

box than at the beginning. The riffles caught the free

gold.

Through the sieve in the end of the long tom the sand was

forced into the sluice-box by a stream of water. As it

passed by slight incline through the sluice-box, gold

being slow of movement dragged back and dodged against

the riffles.

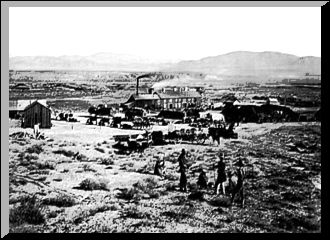

Other Mineral Mining

Many of the old-timer knew very little of horn silver,

chlorides, bromides, or bornites, and what he did know

often did him very little good. On acount of the long

hauls to Denver or Omaha, the cost of building the roads,

and the high treatment charges, the ore had to be rich.

Many were the hardships of these early prospectors in

the Southwest. The minerals were not easy to get like

placer ores of California, nor did they resemble the

free-muilling quartz ores of Colorado, Montana, and

Nevada. They are all smelting, or refractory ores,

and the character of the mineral was different.

They had to be assayed by fire, and often it was weeks

after making a strike before the prospector found out

it's value.

The ore is usually crushed and separated in floatation tanks first,

then calcined (gives off noxious sulphur dioxide) before smelting

with charcoal. This gives an alloy which may contain some or all of

the following, lead, zinc, silver, gold, and cadmium. The latter are only

ever present in tiny levels usually.

Early prospectors relied heavily on burros as they

trekked long distances across the deserts in search

of gold and silver. Many of these burros survived,

even though their owners perished under the harsh

desert conditions. Many more burros escaped or were

released during the settlement of the West. Because

of their hardiness, Wild Burros have thrived throughout

the North American deserts, and their numbers have

increased to perhaps 20,000.

Many miners and prospectors found they had a true friend

they could talk to, palaver with and even complain to,

as well as rely on for survival... a friend who was so

loyal and hard working, so tough and so strong, and

often so reciprocal that their relationship passed the

bounds of simple friendship.

Miners often became so attached to their burros that

they frequently shared their flapjacks and biscuits

with them. And in return, it was these same loyal

friends who always seemed to make sure their owner's

"necessities" somehow made it over the next hill - from

camp to camp - day to day - month in and month out.

Perhaps it's the tenacious nature of burros... perhaps

it's their appealing and loveable nature... perhaps it's

their strength, their loyalty or their endurance... but

one thing's for certain: more heartwarming stories have

emerged from the mining days in the 1800's and early

1900's that feature a burro than perhaps any other

animal.