Well, since I

majored in Environmental Biology at the University

of Montana way back when, I was always walking

around wherever I was stationed and looking at the

flora and fauna, trying to figure out how it all

fit together in that particular ecosystem.

Diego was an especially interesting place, because

it was surrounded by an untouched reef of fabulous

diversity, while the environment on the island

itself was completely artificial - that is altered

by human habitation beyond all recognition of its

pre-human state. A lot of the information I

have about the island came from the Atoll Research

Bulletin No. 149, August 27, 1971 from the

Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, titled

“Geography and Ecology of Diego Garcia Atoll,

Chagos Archipelago” edited by D.R. Stoddart and

J.D. Taylor, and form "Ecology of the Chagos

Archipelago" edited by Charles R.C. Sheppard and

Mark R.D. Seaward.

As for

animal life, the island is composed of coral

rubble and sands laid down since the last Ice Age

(about 12,000 years ago - the period since then is

called the Holocene). Beneath that, about 60

feet below sea level, there is limestone which was

the island during the last Ice Age (called the

Pleistocene, which lasted about 2 million

years). Because of the sand & gravel

nature of the Holocene deposits, fossil evidence

of terrestrial fauna is entirely lacking.

However, it's possible that the islands are very

young - according to Stoddart in 1971, the

surfaces did not peek above sea level until 2,000

to 5,000 years ago (the Holocene began when the

ice sheets melted which caused the sudden 60 foot

rise in sea level - it took corals thousands of

years to grow up to the new sea level). A

couple thousand years isn't generally considered

enough time for endemic species to evolve.

However, it is estimated that during the last ice

age, the Chagos comprised some 13,000 square

kilometers of land, for at least 200,000

years. What we see today is a sandy island

perched on the very top of the mountain that

previously existed. Because of it's

isolation, there may even be remnant populations

of animals evolved during the Pleistocene.

Let's face it, the Chagos archipelago, including

Diego Garcia, was never very heavily populated,

and it's possible something still remains for you

to discover!

The

island was uninhabited when discovered by the

Portuguese explorers in the 1500's, and remained

so until the French arrived in the 1790's to

establish coconut plantations. Of course, as

was the custom in those days, the French

themselves did not do the work on the plantations,

but imported slaves, primarily from Madagascar and

their colonies of Mauritius and Reunion (the

latter two were, like Diego, uninhabited when

discovered by the European explorers - and home to

the famous, but soon extinct, Dodo birds).

Based on linguistic remnants, it appears most of

the slaves ancestors originated in what is today

Mozambique. At any given time, about 500 -

1,000 people lived on Diego Garcia during the

"Plantation Era" from 1786 - 1971.

Above left - Calophyllum

inophyllum (Takamaka tree).

Above right - a bryophyte

growing out of an old stump.

Below left - Ficus

benghalensis, commonly called the Banyan Tree.

Below right - A path through

young coconut trees (Cocos nucifera).

The invasive coconut can be legitimately called a

"weed" on Diego Garcia!

Below: A Banyan Tree takes over the

outdoor latrine at the East Point Plantation Manor

House. This plantation was abandoned in 1971,

and this photo was taken in 1987. The "jungle"

works fast!

Originally,

Diego was covered by hardwood forests. Some

remnants remain at Point Marianne, Mini-Mini, and

around the plantation area. According to the

ARB #149, all the rest of the broadleaf hardwoods

were turned into lumber and shipped back to

Madagascar and Mauritius by the first French

"settlers" in the process of clearing the island for

the plantations. In their place, various

plants in addition to coconuts were imported by the

French and later the British. The most common

was what everyone called "Scaviola" (Scaevola

taccada) bush, which is a broad-leafed succulent

growing to about 20 feet tall on DG, mostly along

the shore - as seen in the composite photo of the

entrance to Barachois La Paille Sec, which we called

"Shark Cove" below.

The Entrance to "Sharks

Cove" (a.k.a. Barachois La Paille Sec - which

means "dry straw")

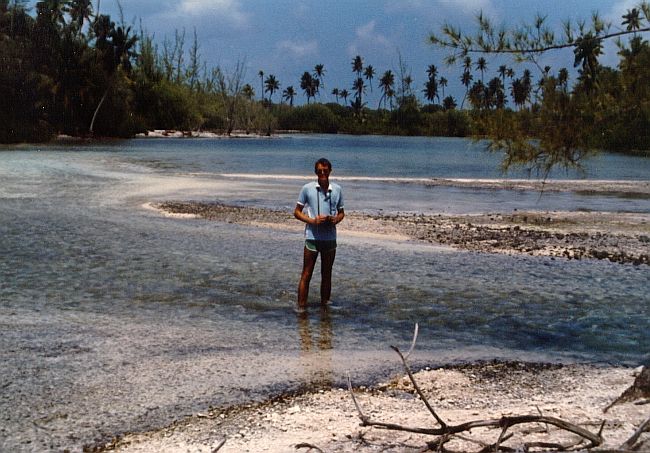

My buddy Steve Swayne at one

of the entrances to Barrachois Maurice, near the

East Point Plantation; 1982.

Above: The

interior of Barachois La Paille Sec with the

tide almost out. The sea grasses you see

on the left dry out between tides and probably

resulted in the name of the barachois.

Below: Barachois Barrer (the central

barachois of "Turtle Cove") at low tide.

One

of the most interesting features of the island were

the "barachois" which has no direct translation, but

most people convert it to "cove". For example,

the three intersecting Barachois of Sylvain, Barrer,

and Courpat are now collectively called Turtle

Cove. In the photos above, Steve is

standing in the mouth of Barachois Maurice, which is

about half way between GEODSS and the

Plantation. These barachois are lagoons off

the main lagoon, and there are several on the

southeastern leg of the island, from the south tip

around to the northeast to the area of the

Plantation (Barachois Lubine). These barachois

were generally dry at low tide, and filled with the

high tide. As tides on DG only ran about 3

feet, these barachois were regularly bathed in

shallow water twice a day. The tide ran

swiftly through the gaps, and it was always

interesting to watch schools of minnows, small fish,

sharks, and turtles come in and leave with the

tide. I assume they were going in to eat

(minnows eaten by small fish, which are eaten by

small sharks, etc., ad nauseum), and you could

clearly watch the Hawksbill turtles chowing down on

algae which covered the coral ledges. However,

these barachois should not be confused with

estuaries or salt marshes. They were sea water

fed and drained, period.

There is fresh water on the surface of Diego Garcia,

but it doesn't "flow" anywhere. Fresh water

marshes around the East Point Plantation were

reported by surveys in the 1960s. There is a

large freshwater marsh just NW of the USAF ("SAC")

ramp on the airfield. This apparently was a

low spot on the island that when framed by the

taxiway, parking apron and road, filled with rain

water. It was filled with aquatic weeds when I

was there in 1988, and is reported to be the home of

Bufo marina toads today. There are several

unstudied and virtually unknown fresh water ponds on

the southeastern arm of the atoll, running

parallel to the ocean-side beach, west of the road,

from the southern edge of the Bomb Dump south past

the Donkey Gate and on for about 1.25 miles.

They can be clearly seen on "Google Earth" (as seen

below). There is no information that I can

find about the origin of these ponds - whether they

are natural fissures or "borrow pits" to build the

road. At any rate, when I took the picture of

one of these ponds in 1988 (also seen below), there

was nothing living in them that I could see other

than algae, although there were hundreds of

dragonflies in the air above them. Hopefully,

someone has stocked them with bluegill and bass by

now, they would make great fishing ponds.

The

Brits kept a very close watch on the environmental

health of the island, and the east arm is kind of

a wilderness area, and visitation by base

personnel is limited and controlled. Most of

the lagoon is a designated RAMSAR (wetlands)

preserve. In 1988, there were three horses

over on the east side, as well as donkeys. I

did see two of the horses, which were quite wild

by that time, over by the Plantation in

1988. I was told one was a gelding (those

damned British Veterinarians must have caught the

poor fellow) and the others a mare and a filly

(never to become a mare with only a gelding

around), so unless a stallion swam down from

India, or snuck ashore off the Mary Jane, the

horse population is extinct out there now, too.

I know

elsewhere in this monologue, I've bad-mouthed the

Brits a little. However, the one thing I

think they did pretty well was ensure the island

was protected ecologically. Basically they

did this in two ways: By making the USN keep

the industrial pollutants contained and remove

them from the island, and by making it a crime,

punishable by the Magistrate of the island (the

Brit Rep himself), for individuals to molest just

about anything but insects (or each other, or, for

most of us, ourselves). For example, a

permit was needed to travel to the east arm of the

atoll, or to build a fire so that people wouldn't

burn down the protective hedges along the

coasts. Once, I watched some BIOT police

arrest a young sailor for pissing on a palm tree

outside the Acey-Duecy Club (though whether it was

for molesting the palm tree, or public indecency,

I don't know). Most especially, it was

absolutely illegal to kill Coconut Crabs, Sea

Turtles, and Spiny Lobsters.

The

Brits attempted to control the predators on the

island, to protect the sea birds and Coconut

Crabs. In 1971 and 72, the Governor of the

Seychelles, who was also the Commissioner of the

BIOT, had the SEABEES kill all a reported 800 dogs

left by the Ilois when they were expelled from the

island. Some say they were shot, others that

they were rounded up and gassed with exhaust from

trucks. They also killed all the pigs (I

hope the pigs didn't die in vain, and at least

provided a luau or two) leaving only rats and

cats. The Brits were always trying to kill

rats, and made every attempt to control the cat

population by rounding them up every once in a

while, putting them in wire cages, and throwing

them into the lagoon to drown.

Unfortunately, they were always catching the "dorm

cats" which were basically pets fed and loved by

the Americans, which caused a lot of hard feelings

by the Americans. It was reported that by

2006 there were only 3 cats left alive on the

island. Also, they then figured they had to

control the chickens, since the cats weren't

around to eat the chicks, and when the chicken

population got out of control (because the cats

had been drowned), the Brits would let the

Filipinos catch them and eat them.

The

Brits also tried to pay attention to the "TCN"

(third country nationals - the Filipinos and

Mauritian workers) on the island. Though

paid a very good wage, compared to what they would

receive at home, these people brought their 3rd

world concepts of nature with them.

Basically, this meant if they could catch it, they

would eat it, and if it meant saving 50 cents for

a meal they wouldn't have to pay for in their mess

hall, then all the better. At least as late

as the 1980s they were always "poaching," and

although no body cared if it was chickens, they

also did not distinguish between sea turtle eggs

and chicken eggs. The classic example of

what they were capable of was that the northwest

end of the atoll was devoid of crabs and chickens,

except in the American dormitory area, where the

GIs and Sailors protected the cats and

chickens. South of the airfield was

generally not visited by the TCNs, and there, the

ecology, artificial though it was, was preserved

from their appetites. Unfortunately,

this may be a preview of what is to come for

Diego. Unless there is an awakening of

environmental responsibility on the part of the

government of Mauritius when the island is

eventually turned over to them, there is a good

chance it will become, literally, a desert island.

INVASIVE

SPECIES

A word

now about "invasive species". This is one of

the hot topics in the environmental world.

Basically, it means a species not originally

native to an area that has been introduced, either

on purpose or accidentally, by man's

activities. The problem with invasive

species is that they sometimes compete with native

species for resources and can alter the natural

balance. Sometimes it leads to extinction of

native species, either the competitor species or

the prey species. Modern examples are the

Brown Tree Snake eating all the native birds on

Guam and Salt Cedars displacing the Red Willow in

the Rio Grande basin. But after a while,

nature balances itself out again, although

extinction is sometimes the price. So,

generally, introduction of new species is

considered a bad thing.

Unfortunately,

sometimes it is too late to stop the invasive

species, as things have already balanced

out. For example, on Diego Garcia, the

terrestrial environment of DG is nothing like what

it was before the arrival of humans.

Basically, the island was clear-cut of its native

forest and replanted with coconut trees.

Over the next 150 years or so, all the terrestrial

land birds were brought in (dove, fodys, mynahs,

chickens, etc.) as were the rhinoceros beetles,

earthworms, ants, toads, geckos, donkeys, cats,

rats, horses, dogs (extinct since 1971),

etc. Also the scaevola was introduced as was

the ironwood (pine-type trees) and any flowering

trees and flowers you see out there. These

invasive species have now formed a biome in which

they co-exist in relative balance. The

problem seems to be that the "native" species,

such as coconut crabs, warrior crabs, sea turtles,

and nesting sea birds have been impacted by SOME

of these invasives, most notably the rat.

The coconut palm grows as a weed everywhere, and

the dense jungle created by young trees

effectively keeps the native hardwoods from

getting re-established.

The UN

has an agreement that says that the host nation

(in this case the Brits) has an obligation to

eliminate ALL invasive species, and some people

want exactly that to happen. Why? What

is wrong with the geckos and donkeys and chickens

and earthworms? Why would we cut down the

Plumeria Trees and all the Ironwood? To

"restore" the native balance would basically

require a scorched earth policy - take the island

down to coral sand and start all over.

And what was the pre-human ecology of the

island? No one knows for sure! So why

worry about it? There is NO GOOD REASON!

It is

absurd to even contemplate the UN's rules.

Do we want to bring back huge colonies of seabirds

and keep sea turtle eggs from being dug up and

eaten? Sure. So eliminate the cats and

rats, and the seabirds and sea turtles will

prosper, and that is a noble goal. Cut down

the coconuts and replant hardwoods. Great

idea. But to go on and on and on as some do

about eliminating all invasives, and using recent

introductions like the toads and agana lizards to

bash the Brits and the Americans is pure

politics.

DG will

NEVER be what it was, and there is no good reason

to try and make it so.

HUMAN USE

AND INDUSTRIAL WASTE

The real

challenge has been the industrial wastes of the

Island, and the Brits at least took their

responsibilities rather seriously - and required

the U.S. to play along. The potential for

pollution on the island came mainly from sewage

from human waste, bulk metals, and POL (petroleum,

oils and lubricants). The USN has a very

comprehensive plan for keeping the environment as

pristine as possible, but let's be honest, unless

the 'host nation' insists on conservation

management, the US Military won't - it's not part

of their mandate. So the Brits are to be

praised for saving Diego Garcia.

The "recyclable storage" area

north of Seabreeze Village in 1987 - now it's the

Golf Course.

There

is a huge sewage plant on the central part of the

northwest point of the island, and another near the

airfield, both easily visible in aerial

photos. The sewage is treated in a tertiary

plant - which is the best there is technically -

with the last step disinfecting. Outfall is

down a pipe into the depths of the ocean.

Scientific expeditions in the 1990s and early 2000s

report that the outfall is deep enough and diluted

enough that the pollutant levels in the surrounding

waters is "virtually pristine".

There

was at one time a huge dump just north of the

airfield, but in the 1980s the monthly supply

ship, the Mary Jane, took away a ship load of that

metal trash to Subic Bay for recycling on each

visit, and most of it was gone by 1988. It

is now the island's 7-hole golf course and as can

be seen on the golfing page on this website, the

place shows no evidence of its former use.

The Navy still stores up metal and ships it off

the island on ocassion. Typically, the US

ships the metal to the U.S., but beginning in 2006

began selling it to recyclers. For example

in 2006, Big Iron Trading Company made 3 trips to

DG to salvage 10,000,000 pounds! of scrap

metal in their ship the MV IRON BUTTERFLY,

and paid $115,000 to salvage the stuff. I

guess recycling pays, but only $23 per ton.

There

was also a landfill for biodegradable trash

located about 2 miles south of the airfield, near

I-Site South. Again, scientific expeditions

have found no trace of pollution from that site

into the lagoon or freshwater lenses.

The fuel

situation was the most challenging, since it

involved the freshwater lenses. On tropical

"desert" islands like DG, fresh water is found

just a few feet below the surface, even though

there are no springs or streams anywhere.

What happens is that the rains (DG had an average

of over 100 inches of rain a year) would seep into

the sandy surface and displace or push out the

salt water that would normally seep into the

aquifer from the ocean and lagoon sides. The

freshwater would settle into a convex "lens" just

below the surface. There are several of

these lenses on DG, and the freshwater for the

island was extracted from them by an ingenious,

computer controlled, complex well field. The

deepest wells are only 15 feet deep, and computers

monitor the water pressure in the lenses, to

ensure not too much water was extracted from any

one lens, which would allow the salt water to

intrude, and the process of rebuilding the lens

begun again. Rebuilding a lens could take

years - flushing of the huge "Cantonment" Lens on

DG would take 4 - 5 years, while the smaller

lenses along the narrow portion of the islands

would flush in just a year or two. There are

about 125 wells from the airfield north.

Ever wonder where the water comes from on

DG? Here's a diagram showing the three

developed lenses (the airfield lenses are not

currently in use as of 2008):

Approximate

extent and depth of the Cantonment and

Airfield fresh-water lenses on Northwest Diego

Garcia. The base uses over 100

shallow “horizontal” wells to produce over

150,000 gallons per day from the “Cantonment”

lens. It is estimated that this 900 acre

lens, which is about 70 feet deep at it's

deepest, holds 5 billion gallons of

fresh water and has an average daily recharge

from rainfall of over 2.5 million gallons, of

which 40% enters the lens. The other 60%

is lost through evaporation and transpiration

from trees - a coconut palm will transpire

about 50 gallons a day!

There are also

small lenses tapped for water at T-Site and

GEODSS.

The airfield wells were drilled after

the construction of the new runway, aprons, and

fuel pits in the early 1980's.

Unfortunately, there were some leaks in the fuel

system, and, as usual on military airfields in the

1970's and early 80's, all sort of solvents,

cleansers, etc., were just hosed off the aircraft

and the aprons into the nearest ditch. There

was a huge amount of fuel stored on the island,

with underground lines leading from the POL pier

near Pt. Marianne to the fuel storage areas and

pits near the SAC ramp, and north of the

airfield. A lot of fuel leaked out into the

freshwater lens at the airfield. As I recall

being told at the time that, there was an

estimated one million gallons of JP-5 (which is

the military name for "Jet A" fuel, which in turn

is basically Diesel No. 2) in the lens, "floating"

(because of its lower specific gravity) on top of

tens of millions of gallons of fresh water, and

that it was extracted using the water wells in

place, and shipped back to the P.I. for

re-refining, although the POL man at the time (Mel

Wasikowski, now sadly deceased) told me that is

was useable just as it came out of the

ground. Although this would be a novel way

to store fuel for future use, it was not the

politically correct solution! So the fuel

was extracted, and I guess by now the airfield

lens has been restored.

Editor's Note 31

Mar 08: Apparently they didn't get it all

at first, or there were other leaks or

spills. From 1996 to 2003 the USAF

conducted "bioslurping" to recover approximately

40,000 gallons of jet fuel from the "SAC Ramp"

area. Read all about it - direct from the

EPA! Click

here and go to page 2 of the PDF for the

article "Large-Scale Bioslurping Operations

Used for Fuel Recovery".

POLITICAL

DRIVEL

Earth First and Greenpeace, you're out

of luck. As much as you might like to

"return" the island to its "natural" state, I

don't think it could be done. The existing

ecology is pretty well balanced, with the cats

eating the chickens and the rats, etc., and the

donkeys kept pretty much in check by salt bloat

(and thus dying young) and castrations.

Someone could rehabilitate the seabird population

if they could kill all the rats and cats from the

donkey fence on southward and up the east arm and

replace the fence with a dike - creating a kind of

wilderness area. They could cut down the

coconut trees and replant with broadleaf

woodland. Of course, that costs big bucks,

and will probably never be done. And of

course, nothing will bring back the extinct local

species that apparently lived there before old Don

Diego Garcia arrived. So, all you hard-core

environmentalists out there, you've got two

choices as I see it - 1) Educate the 3rd

world, and 2) Spend your money on restoration

projects, rather than chasing that Norwegian

whaling ship all over. What? You say

#1 isn't politically correct? And #2 is

first priority? All I've got to say is, if

dolphins are so smart, how come they keep getting

caught in those nets............(apologies to

Dennis Leary).

WHY TRYING

TO MANIPULATE THE ECOLOGICAL BALANCE SELDOM

WORKS

Cindy Qoth's

October 2000 Update - I was reading the Nature

pages, and you mentioned geckos. They are

all over the place now! I really don't

recall there being many, if at all before.

It is really kinda creepy making rounds in the

middle of the nite and walking some places in

BEQ 14, one or twospots with 20 or so of them on

the roof of the walkways and walls. The

make sort of a chirping croak...very

weird. At least they are cute.

The Cattle Egrets have taken the place of all

the chickens, and are all over. There is a

chicken cull every quarter, where only the

roosters are supposed to be taken. Of

course, the hens are, too, and it pissed off

alot of people to have bitty chicks left to fend

for themselves or get eaten by...things.

The frogs/toads whatever are all over the

place...there were more until the rat poison was

put out. The rats were everywhere, so

poison was put out. Then there were less

land crabs and frogs, the flys fed off the

rats, and on up/thru the food chain.

The crabs must be getting hit worst, they eat

the dead rats AND the dead frogs. To top

it all off, the chickens are getting inbred, with many more fluffy

chickens than I recall being around

before. Fluffy ones don't have grown up

feathers, more like downy feathers.

Mike Bodi's

Submittal: The SEABEES take part in the

EARTH DAY, 1972:

|