The Continuing Saga of

Grumman SA-16A Albatros 49-075

Now Called "GRACEY Q"

And Being Restored at Santa Rosa, California

My ship! SA-16A 49-075 on the apron at Dhahran, 1950. This was the 22nd aircraft of this type in the Air Force inventory, and the first to go overseas. Notice the AN/APS 31 radar pod located just inboard of the left wing float. Later models had this radar fitted into the bow of the aircraft.

INTRODUCTION -

FROM MY DHAHRAN WEB PAGE:

It's 1950 when ... from out of the blue, it was

decided to equip Flight 'D' with the brand new

SA-16A 'Albatross' amphibian aircraft just entering

the Air Force inventory. These were the first

SA-16As assigned outside the CONUS.

Four pilots, three crew chiefs/flight mechanics (Nilo P. Pollo, Loyd Cameron and myself), and two radio operators were quickly sent to MacDill AFB, Florida, for two weeks transition training and then to the Grumman Aircraft Factory in New York to pick up the 21st and 22nd SA-16A aircraft delivered to the Air Force - Grumman even put us up in the Belmont Hotel on Manhattan! These were 49-074, and my aircraft, 49-075. Behaving as true crew chiefs assigned to a god-forsaken backwater, TSgt Nilo P. Pollo and I scrounged every available spare part not tied down at the Grumman plant in order to get our aircraft to Dhahran and. keep them flying once we arrived. Our return to Dhahran was via Westover AFB, Massachusetts; Goose Bay AB, Labrador; BWI AB, Greenland; Keflavik, Iceland; Burtonwood, AB England; Wiesbaden AB, Germany; Wheelus AB, Tripoli; and Nicosia RAFB, Cyprus.

At that time a major problem existed with the exhaust system of the Albatross' R-1820-76A Wright Cyclone engines. Nine cylinders emptied into six exhaust stacks and the clamps holding this system together had a bad habit of cracking and breaking apart. This then allowed the unsupported exhaust stacks to crack and break at the cylinder, creating a severe fire hazard-. Needless to say, we made off with every spare exhaust clamp we could lay our hands on.

Another potentially fatal problem we learned the hard way. The SA-16A was equipped with 43D50 Hamilton Hydromatic Reversing Propellers. To permit propeller reversing during water operations there was no interrupt switch mounted on the landing gear such as that normally found on land planes. The propeller were put into reverse by retarding the throttles, located on the overhead quadrant between the pilots, and pushing them up into the reverse detente, which activated a prop-mounted switch which directed the throttles to reverse pitch. Pulling the throttles full back would give up to 70% of rated power for reverse. The prop-mounted switch was located externally on number one propeller blade. We discovered while flying between Greenland and Iceland on our trip back to Dhahran that a very small amount of moisture could keep this switch open and that when the props were in a low blade angle during cruise, the propeller could slip into reverse without any action by the pilot. We were at 8000 feet altitude when the number one engine went into reverse without any warning. The radically changed our attitude of flight! By the time the pilot, Captain Milton Connell, was able to push the feather button, the only action that would bring the propeller out of reverse in this emergency situation, we were passing through 2000 feet on our way to impact with the cold North Atlantic Ocean. I spent WWII in Greenland and on the North Atlantic Ocean with the U.S. Coast Guard, and I didn't want to spend any further time in that area, especially in a rubber raft! Captain Connell regained control and made it into Keflavik. Upon landing the switch was operating normally and the problem could not be duplicated. Only later did we discover the cause of the malfunction, but not before the same thing happened to us again over the Persian Gulf some months later. This problem was finally corrected by a major modification, remounting the switch internally in the propeller hub. But in those early days we could only keep our fingers crossed, for all the help that provided.

Now that we had an aircraft which could land on water, much training was needed. Our water practice take-offs and landings took place in the Persian Gulf, one of the saltiest bodies of water on earth. Corrosion was a serious problem. The normal water supply at Dhahran was brackish and had to be distilled for drinking. The aircraft washdown procedure involved using the fire truck water supply to wash the salt of f , after which the distilled water supply from the 500-gallon white desert truck was used to wash off the corrosive brackish water.

Later in October 1950, while on a training flight in support of our four man para-rescue team practicing an air and land rescue at one of the previously marked aircraft wrecks near the Kuwaiti border, we received word that a 1414th Base Flight C-47 had lost an engine on a flight from Asmara to Dhahran. The aircraft had made an emergency landing on a gravel plain in the desert east of the Saudi capital city, Riyadh. We reached the area and after a search in the late evening darkness, located the C-47 aircraft. We landed and loaded aboard the 23 crew and passengers, made an uneventful night take-off from the open desert gravel plain and brought everyone back to Dhahran. Flight mission time was ten and a half hours.

Two days later a crew member aboard the US Navy tanker USS PECOS, suffering from internal injuries received during a fall, required evacuation to medical facilities ashore. After taking on maximum fuel, 675-gallons in the internal tanks and 600-gallons in two drop tanks, plus four ATO bottles, we were airborne for a flight to a rendezvous in the Arabian Sea over 1000 miles from Dhahran.

On our arrival the PECOS made a continuous turn attempting to dampen Out two very large ground swells--the smaller swell quartering into the larger one. We circled the landing area several times and elected to attempt a landing on the crest of the larger swell. The APU was started and the portable bilge pumps were made ready just in case! Open sea landings were always a hazardous undertaking. On touch down onto the larger swell the aircraft bounced back into the air and landed in the trough between the two quartering swells. Capt. Connell pushed the throttles into reverse and applied full reverse power. We hit the water and stayed there. Attesting to the ruggedness of the SA-16A construction, no rivets popped and no leaks developed. The sea was running fairly high, but with little wind there were no white caps. However, getting the injured sailor, strapped in a stokes litter, from the large metal lifeboat into the plane proved to be a difficult task. From the aircraft a six-man, cabin-stowed life raft was put over the side, a mooring line secured and the raft inflated and allowed to drift to the life boat. The patient was transferred to the raft and hauled back to the SA-16A. Once taken aboard, the patient's litter was secured to the litter stowage rack, the raft deflated and brought aboard. The ATO bottles were removed from their storage well in the bilge between the wheel wells, installed on the ATO mounts on each aft door and everything made ready for an open-sea take-off. The pilot, with a lot of effort, taxied the aircraft onto the top of the large swell. Keeping the aircraft on the crest of this swell, he applied full power and at about 65 knots air speed fired the four ATO bottles for an extra 4000 pounds thrust for 15 seconds. We broke loose from the suction of the water and staggered into the air for our return to Dhahran. This flight lasted 12 1/2 hours. The patient was treated in the base hospital and, before being evacuated to a more sophisticated medical facility, came by Flight 'D' headquarters to give his personal thanks for a job well done.

Thanksgiving Day, 1950, found us once again airborne for another open-sea landing and take-off in the Arabian Sea more than 1000 miles from Dhahran. A sailor on board the USS VALCOUR, the U.S. Navy's Middle East Force flagship, need to return to the U.S. for a serious family emergency. The 10-hour flight required a night open-sea landing, at that time the first of its kind for our new Albatross. The USS VALCOUR provided illumination with search lights, float lights, star shells and two life boats in the landing area. Fortunately the sea was very calm and the landing, transfer of the passenger and ATO take-off were basically routine. The most serious problem of the day was missing out on our Thanksgiving Day dinner. The USS VALCOUR did send over some first rate turkey sandwiches, which were very much appreciated...

Then, in July 2008, I got this email!From: J C & G S Gil [mailto:fennec77@iprimus.com.au]

Sent: Thursday, July 17, 2008 11:13 PM

To: tmorris@zianet.com

Subject: HU-16A 49-075 AlbatrossDear Ted Morris:

I found in the internet your website, excellent histories and pictures about the albatross, to my surprise, your ship 49-075 is my ship now!!

I call her " Gracy Q " and I will be starting restauration pretty soon, is in Santa Rosa California and we like to take her to Argentina and then to Australia where I'm living.

I'm sending some present pictures of her, taken last june.

If you would like to know more or be in touch and exchange histories from her, you can contact me via this e'mail.

Have a good day!

Carlos & Grace Gil

To which I relied:Carlos and Grace,

Thank you very much for your email on my old ship 49-075. You have truly made my day! My year!

I know you will take the best of care of her. I did my best do so those many years ago.

As you know from my web site, she was the 22nd of the Air Force line of the Albatross. The first to go overseas.

I was very proud to have been her crew chief and flight mechanic.

Please let me know how the restoration moves along. I would very much like a photo of her complete re-do.

I have saved the jpgs of 49-075 in your message to my document folders.Thank you again … so very much!

Ted Morris

To which Carlos replied:Hello Ted:

We are very pleased to know that you still love remembering this old lady. Of course we will keep you updated about restoration, but it will be for next year.

We purchase her last June from Lynn Hunt from Aerocrafter, we spend 2 weeks washing, taken bird nests from everywhere and bees, we preserved her as much as we could until we can do something next time.

We found that is still in very good shape, 5400 Hs. TT, no corrosion and this is very important in this type of aircraft.

She doesn't need a mayor restoration, only inspect all the systems, and refit the interior, engines has only 60 Hs. since overhaul in 1995, but we are considering sending them to a workshop for an IRAN inspection, props are in the same situation.

49-075 after service with the USAF 1958, was purchased by Brazilian Airforce as a number FAB 6531, from 10-06-58 to 08-28-1980, then she took the civilian registration as PT-ZAV but she never flew in Brasil until 1995 that Lynn Hunt bought her and flew in 1996 to Santa Rosa, CA. She spend 12 years sitting at this airport as N98HU, We hope not for long.

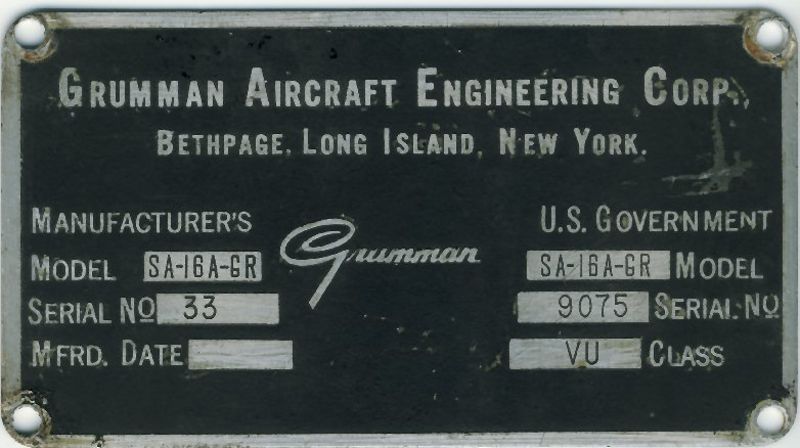

Here I send you some photos with Brasilian Air Force Scheme in the 70', and interior photos as it is now, including the original Grumman plate that needs to be put back again after interior cabin paint work.

Hope you enjoy this photos, and if you have any from your time with her or stories that you would like to share with us, will be very nice!!

Anyhow, we will continue in touch

Have a great day!

Grace and Carlos.

The Progress as of 2008:

Above - the identiplate from 49-075. Note that the Civilian designation is SA-16-GR, and Serial Number is 33.

Below - In service with Forca Aerea Brasileira (Brazillian Air Force)

Note that the radar has been moved to the nose, but the wing slots (outboard of the float plyons) are still there,

so she is still a "short wing" A model.

Above & below - in the foreground is 49-075. Behind her is a restoration to US Navy colors.

Above - interior shot looking forward.

Below - interior shot looking aft.

The insulation has been removed from the interior of the fuselage - it must be one noisy ride!

Above - the cockpit undergoing restoration.

Below - a Hamilton Standard 43D50 propeller.

The black reservoir behind the propeller is the oil tank for the hydraulic prop.

The cylinder around the prop hub is the cooling muff for the prop oil tank.

In October 2011, Carlos wrote again.

"Hope you are all doing well, here I send you a few e'mail with photos of 49-075, after a thorough inspection, we found a few spot of corrosion, so we decided to dissassembly in full to go through the restoration, now is inside the hangar so she will be well looked after.

Hope you enjoy these photos

Keep in touch

take care

Carlos & Grace"

This is a fascinating set of photos!

Who

knew

you could disassemble

an Albatros and fit it in a T-Hangar?

Well, here's proof it can be done!

Good luck to Carlos and Grace on the continuing

restoration.

I'm looking forward to the next set of photos!

Towing her to the hangar. (Cool VW)

Pulling the fuel cells:

Disassembling the empenage (how did the French get to name parts of airplanes?)

Pulling the pylons, fuel tanks and floats.

Pulling the Engines

Pulling the Wings

Looks kind of naked, doesn't

she?

Storing it all away:

The insignia with the Saint Bernard is

the Logo of the Fuerza Aerea Argentina Albatross Squadron

(Argentinian Air Force)

For a full set of photos

featuring 49-075, See Carlos' Flickr collection.

It includes a lot of other Albatrosses too, and a nice

set of her flight from Brazil to California in 1996.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/29034862@N08/

A-Duh-Bee A-Duh-Bee, That's all folks (for now)!

By the way, when Carlos gets her

finished, she'll be the oldest flying Albatross out

there...