| Home

& Index | Email

Me!

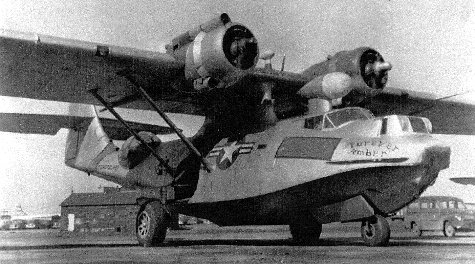

U.S. COAST GUARD PBY-5A 48314 "Forever Amber"  NAS Argentia, Newfoundland 1946-1948 By Lieutenant Colonel Ted Allan Morris, United States Air Force (Retired) Copyright 2001 See a photo page about aerial resupply of USCG LORAN Station, Battle Harbour, Labrador! See

a

photo page about the Rescue of the Sabena Crash at

Gander, 1946, in which 48314 played a role.

Note: The USAF patch featured was presented to USCG personnel operating from the USN Naval Air Station in appreciation for the support rendered in the theater - it was a joint effort up there in those days! |

|

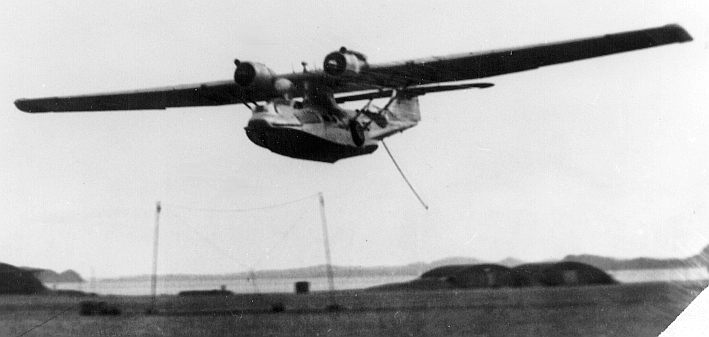

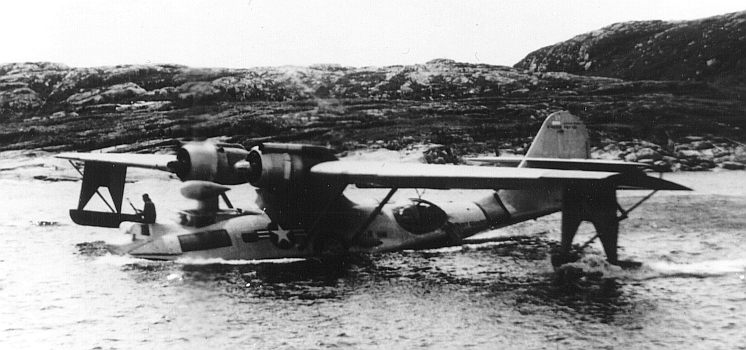

In "Air Combat" Magazine's March 1978 issue, page 56, was a photograph of PBY-5A, 48314, during the rescue operations of survivors from the Sabena Airlines DC-4 crash near Gander, Newfoundland, in September 1946. This article and enclosed photos are about this same aircraft and some activities in which it participated during the next year. The only changes in the aircraft status following the September 1946 rescue operations were that the aircraft was transferred outright to the U.S. Coast Guard, the word "NAVY" was painted out (visible as a bright patch on the fin) and "U.S. COAST GUARD" was painted in small letters on the rudder and in larger letters on the hull immediately aft of the blisters. (See photos.) During these missions PBY-5A, 48314, was part of the U.S. Coast Guard Air Detachment, North Atlantic Ocean Patrol (NORLANTPAT) based at the Naval Air Station., Argentia, Newfoundland. I was a member of this unit as an Aviation Machinist Mate for almost 20 months in 1946-48.  Argentia Naval Air Station, late in W.W. II The Coast Guard has always had numerous responsibilities and some of the ones performed by CGAD Argentia were air resupply of Long Range Navigation (LORAN) Stations in Newfoundland, Labrador and Greenland; air surveillance for the International Ice Patrol; and preservation of lives and property through Search and Rescue (SAIZ). The LORAN stations were, for

the most part, in rather isolated spots. Heavy

supplies, equipment and fuel were supplied during

the summer months by a Coast Guard supply

ship. However, year round, mail, personnel and

high priority items were supplied and retrieved

approximately twice a month by air using the PBY-5A

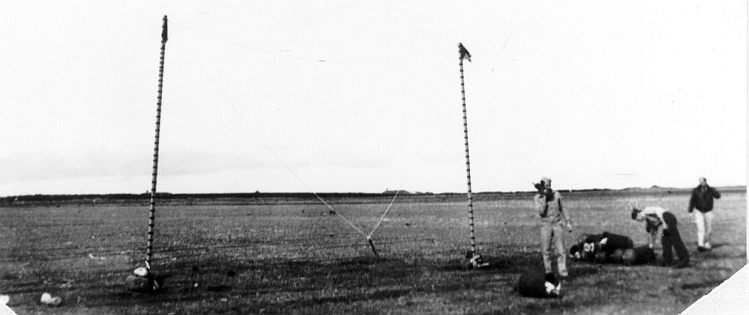

amphibian aircraft. A normal mission to the LORAN Station at Battle Harbor, Labrador, for example, was about eight flying hours for two pilots and four crew members. Prior to takeoff the retrieving equipment was checked over, then the cargo was loaded and distributed throughout the aircraft compartments. The heating system for the crew consisted of three Stewart Warner heaters located in (1) the tunnel compartment (aft of the blisters), (2) the bunk compartment (forward of the blisters) where the SAR equipment was stored, and (3) the navigator compartment (immediately behind the pilots). These heaters used aviation gasoline for fuel, a glow plug for ignition and a minimum of 80 knots airspeed for the air supply that would hopefully mix with the fuel and be ignited by the glow plug. The PBY did almost everything in the neighborhood of 100 knots so the heaters should have worked. Most flights required at least one in-flight heater overhaul to keep at least two heaters in operation. The PBY had plenty of openings around hatches and windows which provided an ample flow of air at outside temperatures throughout the aircraft. It is safe to say that the crew members had better dress warmly and plan on generating most of their own h at. During the air drops and retrieving operations, the heaters were turned off and the blisters and tunnel hatch were open - it was a very cold aircraft. During the air drops the pilots flew the aircraft manually just above stall speed for several hours. The crew members manhandled the cargo to the blister compartment, secured the parachute static line to the gun mount and heaved the bundles out of the blisters as the aircraft flew over the men on the ground. It usually took about eight passes at heights of about 100 feet to drop all the mail and cargo. The tunnel hatch, located at the bottom of the yellow SAR band around the after fuselage, was originally for a .30 cal. tunnel gun. The hatch was about 30 inches long and 21 inches at its widest part. A special rig w as installed on the gun mount through which a two section wooden catcher pole (3 inches in diameter, 20 feet in length) was inserted. Located at the lower end of the pole was a spring-loaded catch into which a hook was attached. A 30 foot length of one-half inch nylon line was attached to the hook. The pole and attached line would trail below and somewhat behind the tunnel hatch. It was, of course, very necessary to secure the other end of the nylon line to a specially mounted stanchion.  Ground retrieval gear used during supply operations at LORAN Stations in Newfoundland, Labrdor and Greenland. The poles, 18 feet high and 20 feet apart held a nylon line loop suspended between them. A cargo container, seen in this photo at the feet of a ground crew member, was used to permit pickup of mail, used parachutes and small items. On the ground the men from the LORAN station would set up the ground part of the retrieval gear. Two poles, 18 feet high, striped red and white, with a small flag at the top of each, were erected about 20 feet apart. Between these poles a 25 foot loop of one-half inch nylon line was stretched and attached. A cylindrical container 20 inches in diameter and 30 inches long, made of hard rubber, with a 10 foot nylon leader was shackled to the nylon loop. During the retrieval operations the pilots flew the aircraft manually for about two hours, literally "buzzing" at a height of about 20 feet. They would fly the aircraft at wave-top level, making it easier to see -the upright poles and make a run at them. As we neared the poles, the pilots eased the aircraft up so the keel would just clear the line between the poles and drag the catcher pole and line across the loop line. As the loop line was snagged, the hook was pulled from the spring catch on the pole and the 30 feet of catcher line, the 25 feet of ground loop and the 10 foot leader line would drag the container into the air. The pilots would then gain some altitude in order to keep the container, strung out behind the aircraft for some 50 feet, from dragging across the ground or into the water. The crew members hauled in the catcher pole to get it out of the way. Two men crouching in the-tunnel compartment hauled in the swinging cargo container hand over hand. The heavy container bounced along at the end of a stretching, straining nylon line, and fingers, arms and legs were easily mashed. With limited room in which to maneuver, it was very necessary to keep everything clear of the nylon catcher line in case someone slipped or the container struck the ground. After the container was aboard, the contents were removed and the container dropped back to the ground for another round of use. It took about 10 passes to make the pickups and it was necessary -to re-rig both the catcher and retrieval gear for each pickup.

On more than one occasion the nose of the aircraft was stuck through the loop. This would snatch the container into the air alright but did not provide a method for getting it into the aircraft. In this situation it became necessary for a crew member to open the bow turret top hatch (contributing greatly to the cooling effect inside the aircraft). As the pilot flew over the ground party, the crew member would stand up in the wind, cut the loop line, and hope the container would fall where the ground personnel could retrieve the contents.

See a photo page about aerial resupply of USCG LORAN Station, Battle Harbour, Labrador!

During the summer months the ice melted and permitted water operations. Mail, cargo and replacement LORAN personnel were flown in and water landings/take-offs replaced the airdrops and pickups. The landing and take-off areas were not always in sheltered water. Each operation was considered an open sea operation and was an experience in itself.

Below the flight mechanics station was an auxiliary power unit (APU) with a built in bilge pump. This APU was manually started with a pull rope that required nimble fingers to wind up and a good standing position when pulling the starter rope in order to start the unit. A fall into the bilges could easily result if you were not properly set. In preparing for an open sea landing, the APU was started and the bilge pump suction line laid out for immediate use. The unit ran continuously while on the water. It provided electrical power for the radio and restarting of the engines as well as operating the bilge pump. Prior to landing, all hatches, nose gear doors and locking pins were checked in place. Normal landing technique was to stall the aircraft onto the water, chop the power and hope it would riot bounce or begin porposing. On one landing in two foot seas in the Belle Isle Straights we took solid water over the propellers resulting in cracked engine nose sections which drastically reduced oil pressure on the very long flight home and required each engine to be changed. The aircraft was taxied using

engine throttles, rudder, sea anchors and putting

the landing gear down -to aid in steering the

aircraft. Each area had an anchored buoy to

which the aircraft could be moored. Depending

on the water and wind conditions, mooring was a wet

job for the crew member in the bow. A catwalk

four inches wide and four feet long was built in

just above water level on each side of the bow

turret. An anchor and mooring post compartment

was located on the port side of the bow. The

crew member crawled out the bow turret hatch and,

crouching on the port catwalk, would rig the mooring

gear. He would then try to catch the eye

splice in the mooring buoy as the aircraft passed

by. This was a two-hand operation, yet it

still took at least one hand to hang on so as not to

slip or be washed overboard. The ice might be

gone but that water was always ice cold.

Water take-offs were usually aided by Jet Assisted Take-Off (JATO) bottles. On each side of the aircraft there were mounts for two bottles forward and two bottles aft of the wing struts. We normally used from two to four bottles mounted on the aft mounts. JATO bottles were mounted onto the aircraft prior to departure from the home station as they were difficult to install from a boat or life raft. A crew member would crawl out

onto the hull and, leaning over the side, install

and connect the JATO igniters. The mooring was

cast off and the bow station secured. The

aircraft was then taxied to the take-off area,

engine power was applied and the take-off run

begun. The JATO was fired by the pilot as near

to lift off as possible to add extra thrust to aid

in becoming airborne. Then it was "get as many

heaters going as possible" and head for home.

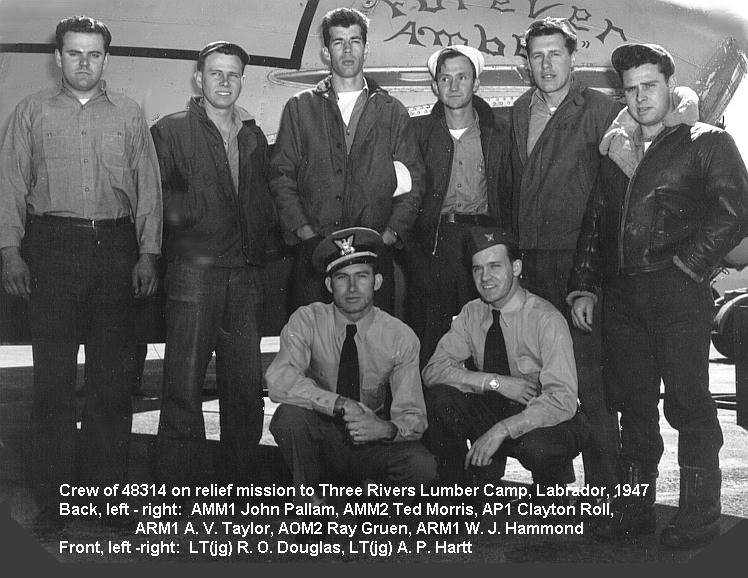

The location, size, speed of drift and estimated course of the iceberg was noted and plotted. This information was provided via radio to all ships sailing in the North Atlantic ice areas. An in-flight meal on these flights was also an experience. The mess hall provided a frozen chunk of meat., two dozen cold-storage eggs, a pound of butter and several loaves of bread. A two-burner hot plate was built in across from the APU. An aluminum frying pan, some pots, dishes and utensils made up the "dining service". The plane captain, who was also the flight mechanic in the Coast Guard, usually did the cooking which made it easier for him to keep the interior of his aircraft clean. The chunk of meat, which never thawed, was hacked into smaller pieces. "Steak" and scrambled eggs was the never-changing menu. The center of the bread always turned to crumbs while the crust seemed to remain frozen solid. Feeding the crew and cleanup was about a two hour task. A primary mission of the Coast Guard has always been to safeguard lives and property and to make every effort to provide assistance to anyone in peril. PBY-5A, 48314, flew many searches and was quite successful in several rescues. In late May 1947 the food storage depot and communications building at the Three Rapids Lumber Estate, Three Rapids, Labrador, about 200 miles northeast of Goose Bay, were destroyed by fire. A lumberman made his way overland 60 miles to the Canadian Radio Station at Hopedale, Labrador, and informed the outside world of the plight of the lumber camp's 150 inhabitants.  The author keeping the aircraft hull from damage during the unloading of emergency supplies at Three Rapids, Labrador. Note JATO bottle between wing struts and blister.

On the return flight with the

four badly burned patients, we also landed at the

Battle Harbor LORAN Station to remove one of their

seriously ill personnel. All in all it was a

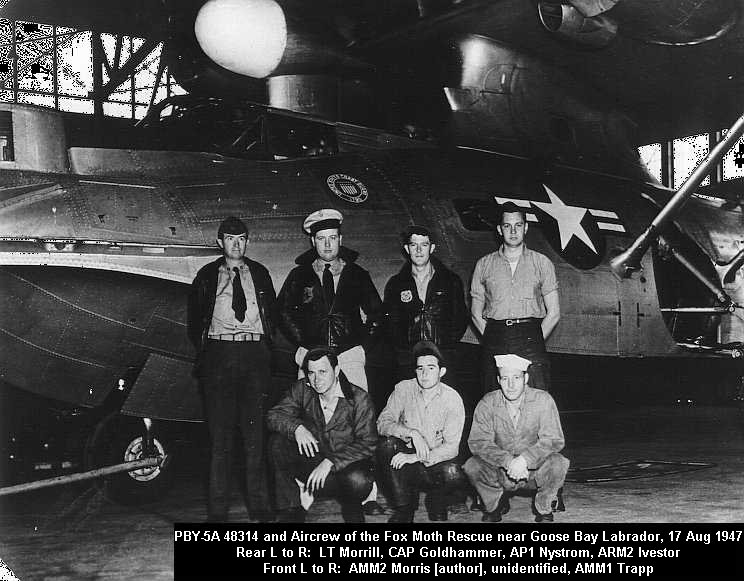

very successful and rewarding mission. Nine days later, on the 10th of August, the Coast Guard was asked to aid in the search. Eight hours into our search a flashing signal was seen near the edge of the lake. As we circled the lake, wagging the wings and making low passes to check out an area for landing, Mr. Mutton never stopped flashing his signal. He had retrieved a piece of engine cowling and spent hours polishing it with a wool sock. He wasn't taking our low passes for granted and kept-signaling until we landed. Crew members rowed a life raft ashore, picked him up and returned him aboard. He had only berries to eat the previous nine days and readily accepted a can of peaches. Mr. Mutton was flown into Goose Bay and gave us all a "Very well done!"

|

|

Aircrew of the Fox Moth Rescue near Goose Bay, 17 Aug 1947

|

| Copyright by Ted A. Morris,

2000 |