|

Air-Sea Rescue at OCEAN STATION CHARLIE United States Coast Guard North Atlantic Ocean Weather Patrol By

Lieutenant Colonel Ted Allan Morris, United States

Air Force (Retired) Article from "The Quarterdeck Log" on the Bibb & Bermuda Sky Queen | Photographs by Michael Dolman, one of the Survivors

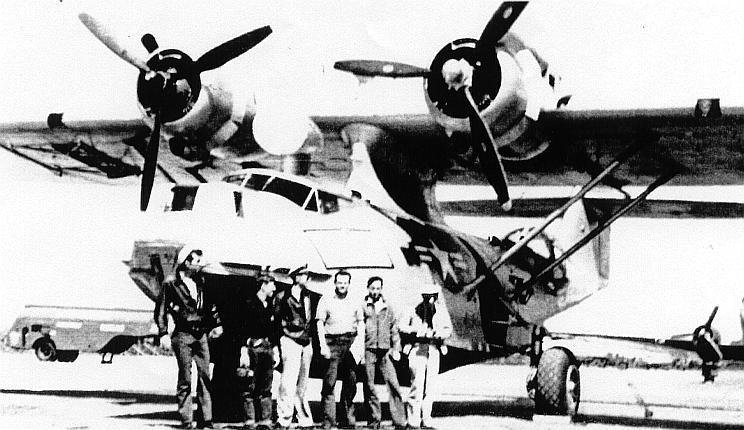

The crew of U.S.

Coast Guard PBY-5A 48314, July 23, 1947

Ocean Weather Patrol, one of the most demanding of the many diversified missions performed by the Coast Guard, began in early 1940 and continued for 37 years. Ocean Weather Patrol was a program in which Coast Guard cutters were assigned to a 10-mile square “Station” on the high seas, and while there, provided world-wide weather forecasting information, collected oceanographic date, and provided emergency navigation assistance and rescue aid for ships and aircraft in distress. Patrols were performed in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, around the clock, every day of the year, including throughout World War II. At its best, duty on patrol was disagreeable and at its worst, it was extremely hazardous. In September, 1942, while on a North Atlantic station, the 250-foot USCGC MUSKEGET, which was converted for war time use from the 1922-built merchant vessel CORNISH, was torpedoed by U-755 and lost with all 121 men. At the end of World War II, eight permanent Ocean Stations were established in the Atlantic, each designated with a phonetic alphabet letter: ABLE, BAKER, CHARLIE, DOG, EASY, FOX, GEORGE, and HOW stations. In the North Atlantic, the Ocean Weather Patrol mission was conducted under the operational control of the Coast Guard’s North Atlantic Ocean Patrol (NORLANOPAT), which also included a Coast Guard Air Detachment and the LORAN Stations in Greenland and along the Atlantic Seaboard of the U.S. and Canada. In the Pacific, six Stations were established: OBOE, NAN, NOVEMBER, SUGAR, UNCLE and VICTOR. Later, the station names were changed to agree with the modern phonetic alphabet. The ships used on these Ocean Stations were the 255-foot OWASCO class, the 311-foot CASCO class (ex-US Navy small seaplane tenders), the 327-foot TREASURY class, and, during the Korean War, the 306-foot EDSALL class (Destroyer Escorts). On the Atlantic stations, most ships operated from either Boston or New York, and would spend 29 to 31 days on station, making weather and sea condition observations every six hours and transmitting the information to one and all. One of these ships was the 327-foot TREASURY class cutter, USCGC BIBB, WPG-31. Her wartime service included convoy escort duty in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, where she made numerous attacks on enemy submarines and rescued hundreds of allied seamen from their torpedoed ships. Following conversion to an Amphibious Force Communications (AGC) Flagship, the BIBB participated in the invasion of Okinawa in 1945.

U.S. Coast Guard Cutter BIBB,

WPG-31. On July 23, 1947, the BIBB and her 150-man crew were assigned to Ocean Station Charlie, and they needed help! A crew member, Seaman Joseph Johns of Helena, Georgia, was seriously ill with a ruptured appendix. The ship did not carry a Doctor, and the Pharmacist Mates on board believed Johns’ condition was beyond their capabilities to help. The Captain considered steaming for Argentia, Newfoundland, but the situation dictated that Johns needed to be airlifted immediately to medical help. Fortunately, another resource available to NORLANOPAT was the Coast Guard Air Detachment based at the US Naval Air Station at Argentia. The detachment had two PB1G aircraft, the Coast Guard version of the four-engined B-17. These aircraft were used for Search and Rescue, and carried a 32-foot life boat slung under the belly of the airplane, as well as other rescue and survival equipment, all of which could be dropped to people in distress at sea. However, the PB1G could not land or take off from the water, and their primary use was flying missions of the International Ice Patrol. This mission consisted of spotting and tracking the ice bergs that break away from the Greenland Ice Cap and drift south into the Atlantic shipping lanes. Reports on the travels of these ice bergs were transmitted to one and all to help prevent a disaster like that of the TITANIC in 1912. Fortunately for Seaman Johns, the Air Detachment also had two long-range PBY-5A twin-engined amphibious aircraft capable of landing and taking off from the ocean. One of these aircraft, PBY-5A Bureau Number 48314, was made ready for the mission. The pilots and aircrew for this mercy mission were Patrol Plane Commander (PPC) LT. William Morrill, First Pilot (PP1P) Aviation Pilot First Class Clayton. Roll, PP2P and navigator, Chief Aviation Pilot Kenneth Franke, and crew members Aviation Machinist Mate First Class (AMM 1/C) John Pallam, AMM 2/C J. C. Entrekin, and Aviation Radio Man First Class (ARM 1/C) Walter Corbett. One essential preparation for this mission was the installation of Jet Assisted Take Off (JATO) bottles. Four 14 KS 1000 JATO bottles, two on each side, were mounted on external racks located on the aircraft hull just forward of the gun blisters. Each JATO bottle, which weren’t “jets” at all, but actually small solid-fueled rocket motors, would produce 1000 pounds of trust for 14 seconds when fired. This extra thrust was extremely helpful in accelerating the aircraft at un-stick speed during takeoffs in rough seas with a heavy load. However, the bottles were practically impossible to mount while the aircraft was on the water, and so they were loaded before takeoff from Argentia. Once these and all other preparation were complete, the crew took the runway for takeoff in the marginal weather, including minimum visibility, for the 600-mile over water flight to Ocean Station Charlie. Upon reaching the BIBB, the crew of 314 prepared the PBY for a water landing, while studying the wind and sea conditions carefully. Open-sea landings were always a very hazardous operation, and the pilots flew back and forth while the ship made several wide turns to help dampen out the surface of the turbulent ocean. Meanwhile, the electrically operated wing floats, which were retracted in flight to form the wing tips to the “P-Boat,” were lowered, and the main wheels checked locked in the retracted position in the sides of the hull. The nose wheel was checked retracted and the nose wheel doors closed and locked shut. The auxiliary power plant (APU) beneath the flight mechanic’s position was started and its output checked, to ensure it was available for the electrical power needed to keep the aircraft batteries charged and provide power for radio communications with the BIBB while the engines were shut down after landing. The APU also powered the aircraft’s built-in bilge pump, which siphoned any sea water that might enter the hull from leaks caused by landing, or open hatches, and provided the needed electricity for restarting the engines. After all preparations were made, and the wind and sea conditions evaluated, the pilots flew the P-Boat ever nearer the ocean surface, and finally made a power-on full stall landing. They applied engine power and controls to keep 314 on the water while preventing an uncontrollable bounce back into the air. After coming to rest, the crew members checked the hull for popped rivets or other damage, and placed the bilge pump hose on the deck in the blister compartment, where the sea would most likely come aboard when the blister was opened to receive the patient.

PBY-5A 48314 makes a power-on, full

stall, open sea landing in the North Atlantic

near Weather Station CHARLIE.

The crew of the BIBB placed Seaman Johns in a wire Stokes Litter, and transferred him from the ship onto the cutter’s 26-foot pulling boat. The boat, manned by six oarsmen and a coxswain to man the steering oar, rowed for the PBY, with Johns and attending medical personnel aboard. They approached 314, which was bobbing up and down on the ocean swell with the engines shut down to prevent a propeller from striking the boat or a crew member. The coxswain edged the pulling boat in close, while being careful to avoid colliding with the plane’s hull, wings or tail plane. The blister hatch was opened, and the patient was quickly transferred into the aircraft and placed in the bunk compartment, just forward of the blister compartment. The plane’s crew secured Seaman Johns carefully, so he would not bounce around and suffer injury during the potentially rough open-sea takeoff. Aircrew member J.C. Entrekin then climbed out the blister onto 314’s hull to make the final electrical check of the JATO firing circuit and to install the black powder igniter into each bottle. However, instead of four bottles, Entrekin found only three. One of the port side bottles had apparently been jarred loose during the open-sea landing. The pilots considered the situation, and decided that an extra 1,000 pounds of thrust on the starboard side would not be uncontrollable, since the bottles were mounted near the center line of the plane, and especially considering they needed all the JATO thrust they could get to make the take-off. They had Entrekin install the igniters and connect the electrical circuits for all three remaining JATO bottles. That completed, the crew member crawled back into the aircraft, soaking wet from the cold ocean spray.

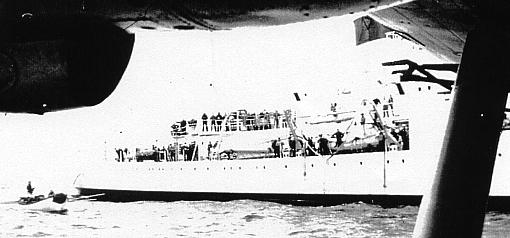

The 26 foot pulling boat departs the

BIBB with seriously ill crewmember Seaman

Joseph Johns The pulling boat backed away, but held a position to stand by in case of an emergency during the PBY’s takeoff. The two engines were restarted and everything prepared for takeoff. Entrekin stayed with the patient in the bunk compartment to assure Johns that all would be well. He was also there to make every effort to get the patient out of the aircraft if things did not go as planned.

The pulling boat from the BIBB approaches 48314. The BIBB had continued her wide sweeping turns to dampen the sea surface, and the crew turned the PBY into the best conditions for takeoff in the rough seas. Lieutenant Morrill handled the controls, while first pilot Roll tried to bend the throttles forward to get all the power available from the engines. At the proper moment, LT. Morrill fired the JATO, and first pilot Roll needed every inch of his six foot four frame to stand on the right rudder to keep 314 on a straight takeoff run. After several bone-jarring bounces, the PBY stayed airborne and headed back to Argentia. With a cruise speed of about 100 miles an hour, it took six hours for the return flight. As they neared their destination, the crew learned that the weather at the Naval Air Station had deteriorated severely, and they diverted to Torbay Airport at St. Johns, Newfoundland.

Seaman Joseph Johns, suffering from

a ruptured appendix, is secured in PBY-5A

48314 After landing, Seaman Johns was transferred to an ambulance and rushed to the U.S. Army hospital at Fort Pepprill for the emergency appendectomy. His appendix had indeed ruptured, and had it not been for PBY 48314 and its crew successfully completing the 1,200 mile, 12 hour mercy mission in terrible weather conditions, he would have died before the BIBB could reach port. The next day, 48314 and crew made the flight back to NAS Argentia. The weather was still bad, and they made several Ground Controlled Approaches (GCAs) before finally landing in zero-zero conditions. After clearing the runway, the tower radioed the crew and informed them they could hear them taxiing past, but couldn’t see them, and as there was no other traffic, they were cleared to taxi to parking, if the “Follow-Me” truck could find it!

Rescue

of the Boeing 314 Clipper Less than three months later, on the night of October 13-14, 1947, the BIBB and an aircraft from NORLANOPAT Air Detachment Argentia teamed up again to make a dramatic open sea rescue. One of the famous Boeing 314 Clippers, The Bermuda Sky Queen, en route from England to the U.S. on a charter flight, encountered 100 mile-an-hour headwinds after passing the “point of no return.” Unable to make the coast, and unable to get back to Europe, the pilot decided to ditch in the stormy North Atlantic at Ocean Station CHARLIE, where the BIBB was once again on Ocean Weather Patrol. A PBY-5A, 48335, was launched from Argentia with additional life rafts and survival equipment to provide air search and rescue assistance if The Bermuda Sky Queen proved unable to reach or find the BIBB. At CHARLIE, the BIBB turned on all possible lights, and maintained radio contact with the clipper until the pilot made visual contact with the ship. Once again, the BIBB made wide sweeping turns in an attempt to dampen out the extremely high seas, and at dawn’s first light, the Sky Queen’s pilot landed his fuel-starved clipper along side the BIBB. While maneuvering toward the BIBB, he water-taxied into the ship, smashing the nose of the Boeing against the ship’s hull. The clipper stayed afloat, and the passengers and crew remained on board the aircraft, but after a couple of hours the heavy seas and high winds forced the cutter and clipper apart. The BIBB then launched all its small boats to the rescue. With skillful seamanship, the boats’ crews rescued all 62 passengers and seven crew members of the ill-fated Boeing Clipper. The P-Boat overhead stood by throughout the rescue, and when no longer needed, turned into the same headwinds that claimed the Sky Queen, and completed the flight with nothing left but fumes in the fuel tanks. One engine starved out during taxi-in. The Sky Queen, with no Aviation Gas available for 600 miles, her nose battered, and adrift in worsening seas, was declared a hazard to navigation, and sunk with 40mm cannon fire from the BIBB. It took a lot of cannon fire - she was one tough old bird... On February 23, 2002, I was thrilled to get the

following message from a survivor of the Bermuda Sky

Queen! What a wonderfully small world the

internet has created... "Dear Mr Morris:

Here's another

contact!

|