|

SOME EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL (EOD) INCIDENTS IN THE STRATEGIC AIR COMMAND 1965-l969 By

Ted A. Morris, Lt. Col., USAF, Retired

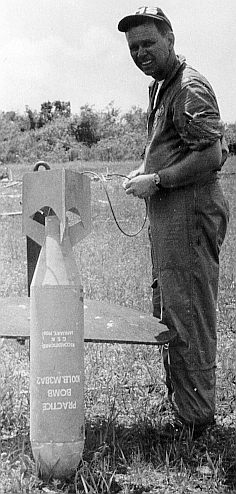

In July 1965, my 22nd year of military service, I began yet one more career, this one an addition to my primary field, Munitions Maintenance. I had just graduated from Explosive Ordnance Disposal School at the Naval Ordnance Station, Indian Head, Maryland. The Air Force assigned me as Maintenance Supervisor to the 29th Munitions Maintenance Squadron (MMS), Homestead AFB, Florida. In 1965 Homestead was home to the 19th Bombardment Wing, Strategic Air Command (SAC), B-52H and KC-135 aircraft. Tenant units included: The 31st Tactical Fighter Wing, Tactical Air Command, F-100; the 319th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, Aerospace Defense Command, F-104G; the 435th Troop Carrier Wing, Air Force Reserve, C-124; the 13th Artillery Group, U.S. Army Air Defense, Hawk and Nike Hercules missiles. As the host command unit we provided munitions and Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) support to each of these units. Munitions and explosives are, by their nature, dangerous. During the next few months after I arrived, our EOD team was to have several serious problems involving each of these units. My first incident started quickly, and with a "bang"! Upon arrival at Homestead AFS my initial concern was acquiring housing for my family. Checking at the Base Housing Office, I was informed there was an on-base house immediately available. In order to be eligible to move into quarters, however, I was required to officially sign in at both Wing Personnel and the squadron to which I was assigned. About noon, after signing in at personnel, TSGT A. W. Bergman, NCOIC of the squadron EOD section, arrived to escort me into the restricted area where the 29th MMS was located. I left my family in our car, saying I would return very soon. At the squadron I completed the necessary paper work which included the application for a Homestead security clearance, and signing a statement agreeing to voluntarily perform hazardous duty (EOD). TSGT Bergman used the EOD emergency response vehicle to drive me back to Wing Personnel. As we departed the MMS area, the truck radio blared, "All disaster control team members report to the flight line assembly point." Bergman said, "You and I are the only EOD personnel available", and we were off to my first EOD incident, unable to inform my waiting family that I would be delayed. An F-105D aircraft on temporary duty at Homestead from the 4th T.F.W. of Seymour Johnson AFB, North Carolina, had crashed on landing. The pilot had been unable to complete a bombing practice mission at the Avon Park Bombing Range, and had returned with most of his explosive ordnance still attached to the aircraft. The fire department personnel had extinguished the initial fire and had rescued the pilot. Our EOD task was to evaluate the condition of the ordnance to see if it could be removed and transported away safely. The major problem was immediately apparent. An AGM-12B Bullpup missile had torn loose and skidded several hundred feet down the runway. The Bullpup used a 250 pound general purpose explosive bomb as the warhead, and had a liquid rocket motor to propel it to the target. The hypergolic liquid oxidizer, Inhibited Red Fuming Nitric Acid (IRFNA), and the fuel, Mixed Amine Fuel (MAF), were contained in separate tanks surrounding the rocket motor. When combined in the motor, they spontaneously ignited with no outside ignition source required. The oxidizer tank had ruptured and was slowly leaking toxic fumes into the air. If the fuel tank also began to leak, a serious explosive accident could occur! Bergman and I secured the Bullpup with sand bags to prevent any unwanted movement, then proceeded to safe and remove the explosive warhead and guidance sections and tracking flares from the motor section of the missile. We now prepared to attempt an inplace controlled deflegration of the leaking rocket motor. In explosive terms, "deflegration" means to have the explosive properties (the IRFNA oxidizer and MAF fuel) decompose (burn) at less than 7000 feet per second. This is preferred to a "detonation" (explosion) which is decomposition at more than 7000 feet per second. In lay terms, we would attempt, using explosives, to make the motor burn rather than explode. Because the leaking liquid was toxic, it was necessary to wear Oxygen Breathing Apparatus (OBA) and butyl rubber protective clothing. The temperature was in the 90 degree range; however, the sweating wasn't due to the heat alone! Our "Rendering Safe Procedures" were successful and following the bright flash and loud whoosh we had the fire department water down and cool off the motor casing. We then collected the remaining explosive hazards and turned the situation over to other disaster response team members to remove the aircraft from the runway. Our efforts had taken nearly six hours. Once again I departed the MMS area, this time to look for my family who had no knowledge of where I was or what I had been doing. They had retreated to the home of an old friend to await my much delayed return. Homestead AFB was a very crowded, busy air base. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, HAFB rapidly expanded from a fifteen B-52H bomber and twenty KC-135 tanker SAC base to a multi-use base with tons of munitions to counter the Cuban threat. There was only a single SW-NE runway and a very crowded aircraft parking area. Three commands (SAC, TAC, ADC) had explosive-loaded aircraft on immediate response alert status. The MMS Munitions Storage Area (MSA) had twenty-one igloo structures completely filled, with additional outside munitions storage between the igloo structures. A severe limitation to EOD actions was a one-half pound explosive limit on a very small EOD range. Munitions and explosives become unserviceable for many reasons and must be disposed of safely. Often they are destroyed by controlled explosions. Just to destroy several rounds of 20mm High Explosive Incendiary (HEI) gun ammunition exceeded our range limits. Unserviceable and hazardous munitions had to be stored safely, separated from other explosives until they were disposed of. Storage space was extremely limited. Often, after much paperwork and coordination, we used a county landfill to dispose of these munitions by controlled detonations. Much was disposed of in off-shore hazardous disposal sites. This required detailed coordination with numerous headquarters to obtain a suitable aircraft on which to carry the often hazardous munitions. EOD personnel were required on board in order to push the munitions out of the aircraft. The US Coast Guard was the most helpful agency. Once they provided a C-123 aircraft for a two-week period enabling us to dispose of nearly thirty tons of hazardous munitions which included 36 US Army HAWK missile motors that had been damaged during Hurricane Betsy of September 1965. One F-100 aircraft accident left us with seven 2.75 explosive warhead rockets scattered along the south side of the runway . The rockets all had been dislodged from the launcher, several traveling hundreds of feet along the ground. These warheads had to be considered hazardous. Forces had acted on the arming devices within the fuses and could detonate if moved or jarred. Also taking into consideration our limited storage capacity for such munitions, we were able to convince the powers-to-be the necessity to "blow in place" (BIP) these warheads. Very carefully separating the rocket motors from the war heads, we proceeded to heavily sand bag each one, and, using an explosive charge, detonated each warhead before anyone could change the SIP decision. The US Army EOD program is the military service charged with assisting civilian law enforcement agencies in matters concerning hazardous explosions. The nearest Army EOD unit was located in Jacksonville, over 300 miles to the north. A written agreement was in-place by which Air Force EOD units at MacDill, McCoy and Homestead Air Force Bases assumed this responsibility for the Army for much of south Florida. Below left: The author prepares a Cuban dynamite bomb for dtonation. Thge bomb was constructed from an M38A2 100 pound practice bomb, filled with about 80 pounds of dynamite, and ignited by a 12-gauge shotgun shell contact fuse in the nose.

Although published Technical Orders outline Rendering Safe and Disposal Procedures for nearly every U.S. and foreign manufactured explosive munitions, each incident can be counted on to be one of a kind. Plans need to be developed on the spot. The average EOD technician needs a lot of common sense and practical knowledge on how to attack the situation to which he is responding. One of my more odd incidents was a request by the National Park Service (NPS) and Florida Fish and Game (F&G) Commission to help save "alligators"! In 1965-66, Everglades National Park was suffering through a drought. Alligators need water to survive. The NPS had a plan and, coordinating with high level AF officials, had our EOD personnel on loan to them to help implement part of that plan. Using explosives (mostly dynamite) confiscated from several Cuban liberation groups by various federal and local law enforcement agencies, we blew holes in the swampy Everglades. The NPS and Florida F&G captured alligators and placed them in the holes into which water had seeped and partially filled. Periodically they would return, feeding the gators to help them survive. Our portion in the plan was to be transported to the selected site by NPS helicopter or air boat and "blow the hole". It was a very hot, dirty job. Several of my predecessors, and successors, also participated in this rather odd yet interesting EOD task. On Christmas Day 1965, a group of teenagers attempted to break into a storage trailer used by a contractor digging a drainage canal several miles to the west of the Air Base. The trailer contained 19,000 pounds of commercial dynamite! Frustrated in their break-in efforts, they set fire to the trailer. The resulting explosion shattered thousands of windows in the town of Homestead. Our EOD team spent several hours locating unexploded dynamite fragments and using controlled explosions disposed of this hazard for the Dade County authorities. Explosive Ordnance Disposal was an additional job for me. During my 14 months in the 29th MMS at Homestead AFB, there were never more than three EOD personnel assigned, myself included. The US build up in Vietnam and South East Asia continually drained conventional munitions personnel from stateside units. During much of the time I was the only munitions officer assigned. In addition to being a busy member of the EOD team I was the MMS maintenance supervisor, the flight line munitions supervisor and acting Squadron Commander. My orders to Vietnam came in September 1966. I was afraid they would be cancelled and I would remain at Homestead. On my departure two experienced munition officers and several senior NCO's were assigned to replace me! Below Left: Scene of the crash of F-104G 60621 in the mangrove swamp between Homestead AFB and Biscayne Bay. The aircraft carried two AIM-9 Sidewinder missles and 20mm High Explosive Incendiary ammunition for its M-61 cannon. Both missiles were found buried in the swamp, and were detonated in place as hazardous explosives.

At the time it crashed, the F-104G had a M-61 20mm Vulcan multi-barreled cannon loaded with 20mm HEI ammunition and two AIM 9 Sidewinder missiles. The 20mm was exploding and the two AIM 9 missiles could not be immediately located. The pilot had not survived and our EOD team was tasked to safe the area so his body could be recovered. We waited until the 20mm stopped exploding and returned to search for the Sidewinders. Locating the first one, we proceeded to blow in place the solid fuel motor, the warhead and guidance unit. All had broken apart and we considered them to be extremely hazardous to attempt to recover. Setting our explosive charges and retreating from the swamp to a safe area, the first missile was disposed of safely. We were then able to recover the pilot's body. Because of darkness operations ceased. The next day we located the second Sidewinder six feet deep in the black swamp ooze, destroyed it and the remaining unexploded 20mm ammunition. Numerous people had arrived near the crash site. One, a ranger from the Florida Fish and Game Commission, was concerned about damage to the ecology and wildlife. During our conversation, I commented, "When I jumped into that canal and mangroves, all I could think about was disturbing some big, mean alligator." "You don't need to worry about alligators," the ranger replied. "They're fresh water creatures. This water is too brackish and salty for them. This is crocodile territory! Albeit smaller than the American gator, but quite fierce in their own right." In September 1966 I departed Homestead AFB for a tour in Vietnam. But that is a separate Story.

Left: 51st MMS

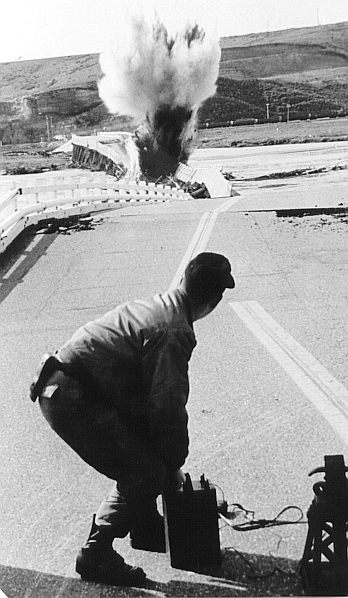

Patch. A large problem, however, came from the World War II use of Vandenberg, then known as the US Army's Camp Cooke, an artillery and tank training center. Lots of W.W.II munitions, mostly inert training items, were spread over the 98,000 acres of the Air Force's third largest base. Though most items were inert, there were also many live items, including hand grenades, 2.36 inch bazooka rocket motors and warheads, 75mm and 105mm artillery projectiles. Dependent children, including my own, roamed the base and were the finders of many of these hazardous items. On one occasion two young boys located, and took home, a 2.36 inch bazooka rocket and three 75mm projectiles. One was a solid steel round, the other two were armor piercing rounds, explosive loaded with base detonating fuses. All three had been fired from a gun, were rusty, and extremely hazardous. Fortunately the mother contacted the Air Police, who in turn called us. We set up the bazooka rocket and two explosive loaded rounds for detonation on our disposal range with several cardboard target silhouettes around to simulate what would happen to bystanders when these items detonated. We asked the base newspaper to cover the story, and had the two boys and their parents on hand to witness the demonstration. Several of the silhouettes were demolished, the others riddled with shrapnel holes. Those looking on at the demonstration were measurably impressed. The printed story and photos in the paper brought a flood of recovered W.W.II ordnance items, a large number containing live explosive. Below Left: Staff Sergeants F. L. Evans and F. Powlas prepare to place an exposive charge to clear debris from the collapsed Surf Bridge which was acting as a dam across the Santa Ynez River on Vandenburg AFB.

The next to the last bridge crossing the Santa Ynes was located on Vandenberg about 1,000 yards From the ocean. Built during 1942 to handle tanks and other heavy military traffic, the Surf Bridge had been constructed on top of a salt water barrier of huge concrete blocks sunk into the river bed. The purpose of this barrier was to prevent ocean salt water from encroaching onto surrounding farm land used to grow commercial flower seeds. A very colorful valley in normal times. Much debris had piled against the upstream side of the bridge creating a dam. Roaring water flowed over the bridge and poured down alongside the salt water barrier. This action along with the pressure against the dammed side caused the bridge to tilt onto its side creating an extremely effective dam across the river. After the initial storms ended and first flooding eased, the Air Force contracted to have the Surf Bridge, now a dam, removed. Before any action could take place, new storms developed and a second flood rushed down the Santa Ynes. The Air Force was now faced with billions of dollars in law suits for having not cleared the obstruction from the river. In the early hours of a Friday morning, our EOD team responded to a call to do something to remove the Surf Bridge dam. Using all the explosives we had on hand, jack hammers, cutting torches, and power saws, over a period of several hours we succeeded in blowing a sixty foot wide gap in the collapsed bridge allowing the river to flow through. The Air Force then authorized us to blow apart the remains of the bridge in order to drag it ashore for salvage. Obtaining several hundred pounds of commercial dynamite and detonating cord, we worked through the week end and were successful in severing several sections of the bridge, clearing much of the large trees and other debris from the dammed river. That Monday morning the third and final flood roared down the Santa Ynes River, washing many of the severed bridge sections out into the Pacific Ocean. To this day Surf Bridge has never been rebuilt ...

SSgt Powlas and I leave the Surf Bridge after placing explosive charges.

SSgt Powlas

detonates an explosive charge.

|

In the Miami-Dade County area there was

much activity by groups dedicated to the overthrow of

Castro and liberation for Cuba. Some ingenious

explosive weapons had been developed by these groups

to use in their cause. On one occasion, children

had located about two hundred 2.75 inch rackets and

were playing throughout their neighborhood with these

live explosive units. Coordinating with the FBI

and Dade County sheriffs' authorities, our EOD

Personnel collected these rockets, transported and

stored them until they were freed to be disposed of by

us. On another occasion, a group had acquired

numerous M38A2's, 100 pound practice bombs.

These bombs, made of sheet metal, were painted blue,

with the nickname "Blue Whistler". They were

filled with sand with a small spotting charge when

they had been used to train bombing crews during

W.W.II. The Cuban group had packed the bomb with

about 80 pounds of commercial dynamite and had

manufactured a nose cone packed with plastic C-4

explosive and a 12-gauge shot gun cartridge as a

contact nose fuse. They had dropped several of

these in Havana from small aircraft. The FBI had

located quite a few of these and asked us to

demonstrate the effect this bomb would produce, and to

destroy the remainder. These Cuban bombs

designed to detonate on contact would cause

considerable blast over-pressure.

In the Miami-Dade County area there was

much activity by groups dedicated to the overthrow of

Castro and liberation for Cuba. Some ingenious

explosive weapons had been developed by these groups

to use in their cause. On one occasion, children

had located about two hundred 2.75 inch rackets and

were playing throughout their neighborhood with these

live explosive units. Coordinating with the FBI

and Dade County sheriffs' authorities, our EOD

Personnel collected these rockets, transported and

stored them until they were freed to be disposed of by

us. On another occasion, a group had acquired

numerous M38A2's, 100 pound practice bombs.

These bombs, made of sheet metal, were painted blue,

with the nickname "Blue Whistler". They were

filled with sand with a small spotting charge when

they had been used to train bombing crews during

W.W.II. The Cuban group had packed the bomb with

about 80 pounds of commercial dynamite and had

manufactured a nose cone packed with plastic C-4

explosive and a 12-gauge shot gun cartridge as a

contact nose fuse. They had dropped several of

these in Havana from small aircraft. The FBI had

located quite a few of these and asked us to

demonstrate the effect this bomb would produce, and to

destroy the remainder. These Cuban bombs

designed to detonate on contact would cause

considerable blast over-pressure.  One other incident will bring my

Homestead AFS EOD experiences to a close. On 21

September 1965 the air base was conducting a practice

disaster exercise which included all our EOD

personnel, myself, SSGT R. Gillespie and AlC J.

Kitzmiller. Two F-104G alert aircraft were

scrambled, taking off to the N.E. One aircraft

developed problems and crashed into the mangrove swamp

between the Air Base and Biscayne Bay.

Terminating the practice exercise, the disaster team

proceeded to the site of the crash. By chance,

our EOD team was the first to reach the area adjacent

to the crashed, burning aircraft. SSGT Gillispie

and I proceeded into the swamp laced with canals dug

years ago to improve the ebb and flow of the brackish

salt water. The purpose of this was to reduce

the ability for millions of mosquitoes to breed and

hatch. It was not working well that day!

We plunged into a rather wide and deep canal, working

our way through the mangroves in an attempt to reach

and rescue the pilot of the aircraft.

One other incident will bring my

Homestead AFS EOD experiences to a close. On 21

September 1965 the air base was conducting a practice

disaster exercise which included all our EOD

personnel, myself, SSGT R. Gillespie and AlC J.

Kitzmiller. Two F-104G alert aircraft were

scrambled, taking off to the N.E. One aircraft

developed problems and crashed into the mangrove swamp

between the Air Base and Biscayne Bay.

Terminating the practice exercise, the disaster team

proceeded to the site of the crash. By chance,

our EOD team was the first to reach the area adjacent

to the crashed, burning aircraft. SSGT Gillispie

and I proceeded into the swamp laced with canals dug

years ago to improve the ebb and flow of the brackish

salt water. The purpose of this was to reduce

the ability for millions of mosquitoes to breed and

hatch. It was not working well that day!

We plunged into a rather wide and deep canal, working

our way through the mangroves in an attempt to reach

and rescue the pilot of the aircraft.  On my return from Vietnam I was

assigned to the 3901st Strategic Missile Evaluation

Squadron, Vandenberg AFB, California. My job was

to evaluate the munitions and EOD support of SAC's

Minuteman and Titan II missile bases located

throughout the US. Five months later I was

reassigned as Commander, 51st Munitions Maintenance

Squadron, also at Vandenberg AFB.

On my return from Vietnam I was

assigned to the 3901st Strategic Missile Evaluation

Squadron, Vandenberg AFB, California. My job was

to evaluate the munitions and EOD support of SAC's

Minuteman and Titan II missile bases located

throughout the US. Five months later I was

reassigned as Commander, 51st Munitions Maintenance

Squadron, also at Vandenberg AFB.  Once

again SAC was the host command and provided support to

several commands involved with missile development and

testing (Air Force Systems Command, Aerospace Defense

Command and the National Aeronautics and Space

Administration). Numerous aerospace contractors

supported these commands. There were many

unusual rocket and missile motors and related

explosives to be concerned about.

Once

again SAC was the host command and provided support to

several commands involved with missile development and

testing (Air Force Systems Command, Aerospace Defense

Command and the National Aeronautics and Space

Administration). Numerous aerospace contractors

supported these commands. There were many

unusual rocket and missile motors and related

explosives to be concerned about.  One final and rather unusual EOD job

finishes what I hope has been a few interesting

incidents.

One final and rather unusual EOD job

finishes what I hope has been a few interesting

incidents.