|

By Lieutenant Colonel Ted Allan Morris, USAF, Retired

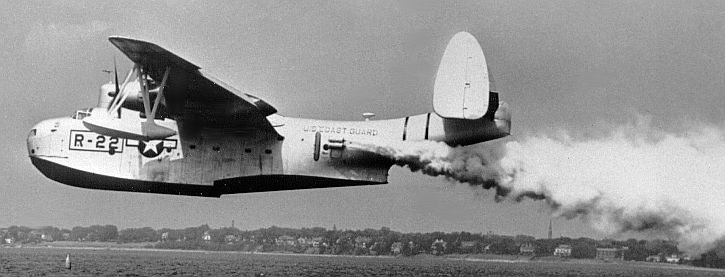

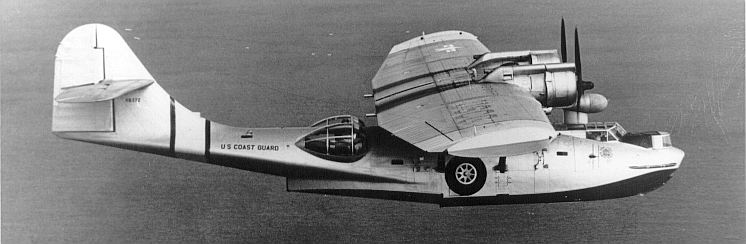

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5 At CGAS St. Petersburg the normal week began on Monday morning at 0800 hours with a muster of all personnel. Air Station compliment was only about one hundred commissioned and enlisted personnel. Most were aviation ratings: machinist mate, radioman, ordnanceman, parachute rigger, metalsmith. Non-aviation rates included cook, yoeman, storekeeper and boatswain mate. The aircraft we operated were two PBM-5 Mariners, three PBY-5A Catalinas, one JRF-5 Goose and two J4F-2 Widgeons. There were also all sorts of motor vehicles. In addition, there was a 30-foot aircraft crash boat, a 38-foot picket boat and an 83-Foot patrol boat.  Grumman JRF-5 Goose Amphibian. About 25 were used by the USCG during the 1940s & 1950s for short range Search and Rescue Missions. The aircraft had a gross weight of 8,700 pounds with 220 gallons of fuel. Range 800 miles at about 150 mph. Powered by two R-985-AN6 9-cylinder Pratt and Whitney Wasp Jr. engines, producing 400 horsepower at take-off. Each engine required 18 spark plugs. This morning muster began a three week duty rotation cycle. Following this daily muster, everyone "turned to" and went about their normal assigned duties. This week, Section I was designated the "duty" section and Section II the "stand-by" section for Monday. At 1700 hours, Sections II and III were granted varying degrees of liberty and were free to "go ashore". In the event an emergency occurred (something more than the duty section could handle without augmentation), the stand-by duty section, Section II, would be recalled back "aboard". Section III was on relatively unrestricted liberty until the next morning 0800 muster. After 1700 hours the duty section (Section I) would complete any unfinished maintenance and perform "evening operations". This meant the launch and recovery of one of the smaller aircraft (JRF-5 or J4F-2) which conducted a two hour offshore flying patrol looking for any potential emergencies such as a disabled pleasure or fishing boat, or swimmers who had over extended themselves too far from shore, often on an air mattress. To these people this precautionary patrol quite often proved the difference between being a survivor or becoming a missing person. The duty section provided the security and fire protection "watches" during the 1700 to 0800 hours of the duty period and any other of the many additional task needed to keep the Air Station Functioning 24 hours a day. There was no other specially assigned group to perform these numerous duties. For Section I the day ended at 2200 hours with various duty section personnel assuming watch duties, including the security and Fire protection patrols and the 24-hour a day radio monitoring and listening watch. The following day (Tuesday) began at 0600 hours. Section I, still the duty section, would preflight the "ready alert" rescue aircraft (normally one of the PBM-5 and one of the PBY-5A aircraft). At 0800 hours all three sections mustered again and everyone then went to their normal duties. Section II became the duty section and Section III the stand-by duty section. At 1700 hours Section I (after 33 continuous hours of work, watches and duty) would begin a relatively unrestricted 15 hour liberty until the Wednesday 0800 hour muster. At that time Section III became the duty section and Section I became the stand-by duty section. This rotation of duty went on seven days a week, 365 days a year. For Section I, the duty/work hours from Monday 0800 muster through Saturday 0800 muster totaled to seventy-five (75) hours: Monday and Thursday - 2 days X 24 duty/work hours plus Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday - 3 days X 9 work hours. Everyone got an equal opportunity! Section II worked those duty/work hours the second week of the cycle. The following week Section III did its share. But wait! Saturday and Sunday have to be accounted for! At 0800 hours Saturday, the off-going duty section (Section II) and the on-coming duty section (Section III) would muster. Section II then began an unrestricted 24 hour liberty until 0800 hours Sunday morning when it became the stand-by duty section. (On Saturday and Sunday only the on-coming and off-going duty sections need be at the Air Station to muster. The section assuming stand-by duty automatically began its restricted liberty period.) The Saturday duty section, Section III, then took care of any jobs that needed to be done. Other than the previously mentioned watches, there was no routine maintenance scheduled unless more than one aircraft was out of commission. In such case, it was necessary to work until the accepted in-commission rate was met. At 0800 hours Sunday, Section I reported for muster as the duty section. Section III began unrestricted liberty until 0800 hours Monday. Section II automatically became the stand-by duty section. Sunday's routine paralleled Saturday's. By the time Monday's 0800 muster occurred and all sections met to start a new week, an additional 24 hour duty/work day (Sunday duty) had been added to Section I's previous 75 hours. A grand total of 99 duty/work hours For the seven-day week. When subtracted from the 168 hours available in a week, 69 hours were left for our man in Section I, provided he was not needed on one of his stand-by duty days. Sections II and III each had the same opportunity for long hours during the three week cycle: Two weeks with 99 hours, and one week with 75 duty/work hours.  Martin PBM-5 Mariner Seaplane. About forty were used by the USCG during the 1940s and 1950s for long range Search and Rescue missions in the U.S. and overseas. The aircraft had a gross weight of 56,000 pounds with 2,670 gallons of fuel. Range was 2,700 miles at about 120 mph. The PBM was powered by two R-2800-34 18-cylinder Pratt and whitney Double Wasp engines which produced 2100 horsepower each at take-off. Each engine required 36 spark plugs. If the emergency required the launch of one or more of the Coast Guard aircraft, the 38-foot picket boat, or 83-foot patrol boat, the stand-by duty section was recalled to replace the duty section personnel responding to the emergency. During the years I served in the Coast Guard this happened at least once a week! In addition to our primary duties, each ship and station had a "Watch, Station and Quarters' Bill". This translated to a lengthy list outlining the specific duty each man was to perform during a "situation". For example: On an aircraft search and rescue (SAR) mission, you could be an aircrew member, or a member of the ground or beaching crew assisting in launching or recovering the aircraft. Or, during a Fire emergency, you could be the asbestos suit man or fireman on the fire truck. These duties were in addition to your primary duties. Every conceivable contingency was covered. I was an Aviation Machinist Mate Second Class (AMM2/AD2) assigned to Section I, and had at least three major aviation related jobs assigned as primary duties. I was an aircrew member Flying as a flight engineer on regularly scheduled training flights, emergency "mercy missions", and search and rescue (SAR) missions. SAR missions could last From 8 to 10 hours and might continue for several days. I was a ground maintenance mechanic for scheduled and unscheduled aircraft inspections and maintenance. My primary "primary" job was to operate the one-man spark plug shop.  Grumman J4F-1 Widgeon Amphibian. About 25 were used by the USCG during the 1940s and 1950s for short range Search and Rescue Missions. The aircraft had a gross weight of 4,525 pounds with 108 gallons of fuel. Range was 750 miles at about 135 mph. Powered by two L-440-5 6-cylinder Ranger engines which produced 200 hoursepower at take-off. Each engine required 12 spark plugs. Whenever an aircraft amassed 30 hours of flying time, it was necessary that the aircraft undergo a scheduled maintenance. The 30-hour time period was accumulative: 30, 60, 90, up through 240 hours. Each time period required more systems to be inspected and maintenance on them be performed. At 240 hours flying time the cycle would begin over again. For example, at 30 hours, maintenance required that: - all oil and fuel systems' strainers be removed and cleaned; - fuel, oil and hydraulic hose lines be checked for damage and properly secured; - propeller blades be filed free of nicks and other damage caused by salt water abrasions; - landing gear wheels and brakes be removed and cleaned to remove corrosion; - wheel bearings be repacked and re-installed; - the entire aircraft be washed to prevent corrosion caused by salt water emersion. Those were just a few of many required tasks to be performed. At the 240 flying hour period, in addition to those functions performed during each of the other maintenance periods, it was necessary to: - reset valve clearances; - replace all spark plugs (also required at 60, 120, and 180 hour periods); - reset magneto timing; - replace many hoses; - check instrument settings and operation; - check of proper tension for control cables. The list was extensive and many hours were required to accomplish these tasks. Unscheduled maintenance could occur at any time in order to fix broken aircraft parts, starters, generators, fuel and oil lines, cylinders that needed replacement. Each aircraft had lots of working parts, many with short life spans. My primary job was to operate the one-man spark plug shop. In today's world of turbine aircraft engines it is difficult to imagine a spark plug shop, but it was an important part of the piston engine world of yesterday. Each piston driven aircraft engine cylinder used two spark plugs. Our PBM-5's had two 18-cylinder R-2800 Double Wasp engines requiring 72 plugs.. The PBY-5A's two 14-cylinder R-1830 Twin Wasp engines needed 56 plugs. The JRF-5's two 9-cylinder R-985 Wasp Jrs. used 36 plugs, while 24 plugs served the smaller J4F-2's two 6-cylinder V-440 Ranger inline engines. Multiplying the total number of aircraft assigned at CGAS St. Petersburg by the number of cylinders, the spark plug requirements amounted to 396 installed plugs, with an equal number available in the "ready locker" as instant replacements. Spark plugs were also maintained for all the motor vehicles, ground power equipment and power boats we possessed.  Consolidated PBY-5A Catalina Amphibian . About 115 were used by the USCG during the 1940s and 1950s for long range search and rescue. The aircraft had a gross weight of 34,000 pounds with 1,475 gallons of fuel. Range was 2,550 miles at about 115 mph. Powered by two R-1800-92 14-cylinder Pratt and Whitney Wasp engines which produced 1,200 horsepower at take-off. Each engine required 28 spark plugs. Aircraft engines were voracious consumers of spark plugs. Engines that became over heated or were operated too cool, or fuel mixtures that were too rich or too lean, all had adverse effects causing spark plugs to burn out or become Fouled. Often it was necessary to replace all engine plugs to correct ignition problems that might have developed between the scheduled 60-hour replacement. The salt water environment in which Coast Guard aircraft operated took a heavy toll on all of the aircraft and engine parts. You have been introduced to several of the requirements necessary to operate a Coast Guard Air Station twenty-four hours a day, and how personnel were utilized to meet those requirements. Mostly we have discussed the Monday through Friday operations. But, remember, we said the operations continued seven days a week throughout the 365-day year. Let me take you on a "Sunday With The Duty". I am sure you will note that none of these specific jobs this Sunday involved aircraft, but they were the responsibility of the U.S. Coast Guard. On the "Watch, Station and Quarter Bill", I was assigned as a coxswain for the 38-foot picket boat for "situations" requiring its use. This was a very sturdy, wooden hulled, 38 foot long boat with a 225 hp gasoline engine. It had been developed during the 1930's to patrol against and capture of "Rum Runners" during the "Prohibition Wars", and was designed primarily for use in inland and coastal waters. The coxswain was the primary operator. He had to be both a seaman skilled in small boat handling (especially in rough water and in emergency type conditions) and motor machinist. He was also charged to be a law enforcement officer should the occasion require him to exercise that function on the navigable and ocean waters of the United States. The boats were the primary job for Boatswain Mates. Only one BM was assigned to CGAS St. Pete, however, and he was in another section. On a "Sunday With The Duty" in late 1948, there was

to be a sail boat race from the St. Petersburg Yacht

Club to Egmont Key, an island off the entrance to

Tampa Bay. After a picnic on the island the

boats would return later that afternoon. We were

to patrol the race and render any assistance

needed. So, instead of standing the Sunday

morning 0800 muster, a radioman and I prepared the

picket boat and were at the race starting line at 0800

hours.  A 38-foot picket boat. About 540 were built by several differnt companies in Michigan, Washington, Maine, Massachusets, and Florida during the 1930s & 1940s. Initially used during the Prohibition War and carried unitl the 1950s for law enforcement and Search and Rescue missions along coastal and inland waterways. The wooden hulled boat used a 6-cylinder 225-horsepower Hall Scott or kermath gasoline engine. Range was about 200 miles at 10 knots. After seeing all the boats safely to Egmont Key and not having been invited to the picnic, we began our return to the Air Station. Just underway, we spotted a man treading water in the deep water ship channel! As we approached to offer assistance, he shouted that his power boat had run aground about a mile away, close to the mangrove swamp that formed the shore line. We picked up the swimmer and went to his boat. As we eased our picket boat in close to his power boat, the swimmer took to the water with a tow line which he secured to his vessel. Applying power, we were able to pull his boat free and into deep water. When we asked what he was doing in the ship channel, he replied that he had seen us go by on our way out with the race and decided to swim out to await our return and assistance! After this small adventure we returned to the Air Station to top off the fuel tanks and get something to eat. Our next duty that day was to recover a dead

body! In 1948 the Sunshine Skyway Bridge joining

St. Petersburg with Bradenton/Sarasota had not yet

been built. The means of crossing the entrance

to Tampa Bay was by way of the Pinellas County

Ferry. On one of the ferry crossings that Sunday

someone reported seeing a body floating on the water's

surface. Once again we got underway in our

picket boat. Reaching the reported area, we

began a search. We did not locate a human

body. We found, instead, the badly decomposed

carcass of a large animal. We assumed it had

been dumped, for some unknown reason, from one of the

large ships making its way to or from the Port of

Tampa. Radioing the Air Station to notify the

county sanitation department to take care of the

"body", we then towed the carcass to the St. Pete side

of the Ferry route. Returning to the Air Station, the tanks were once again refueled to the top so that the picket boat would always depart on a mission with full tanks. We were again dispatched by CGAS Operations Center, this time to tow a disabled pleasure boat with six people on board back to the marina. Locating the disabled craft and towing it to the marina took several hours. It was dark when we reached our destination. As we prepared to depart the marina, an eight year old boy came onto the dock asking for our help. He had gone ashore from his parents' pleasure boat, moored across the marina from us, while his parents were absent. Upon returning, he said, he found the boat's lights were out. Insisting the lights were on when he left, and thinking someone was on the boat, he was afraid to go on board. Taking a CO-2 fire extinguisher as my only weapon, I went around the marina to help the boy. The radioman requested the Air Station to notify the city police to assist. Going aboard the moored boat, I could locate no one and turned on the lights for the boy. About this time the police arrived, taking over the responsibility for joining the boy with his parents. Before we left the marina For the last time that day, I asked the young boy why he had come all the way around the marina to ask for our help rather than someone else. He explained that his father told him if he ever needed help, that anyone on a boat like our distinctive U.S. Coast Guard marked picket boat would help him. That simple statement made my whole tour of duty worth the effort. Now, at nearly 2200 hours on our "Sunday Duty" night, we returned to the Air Station to refuel once more and hopefully secure the picket boat for the day. But our duty wasn't over. Operations had received a report that distress flares had been seen off Gadsden Point, near MacDill Air Force Base. Once more we were dispatched. Arriving at the reported area, we set up a widening search pattern in the dark. After about 45 minutes into the search we located a pleasure boat with two Air Force sergeants. The boat, its engine disabled, had drifted onto a shoal and was hard aground. One of the men had gotten into the water in an attempt to push the boat off, but his efforts were unsuccessful and his companion had not been able to get him back into the boat. He had been seriously cut by barnacles and was suffering from salt water immersion. The radioman and I successfully got the man out of the water and into the picket boat. We then towed their boat free of the shoal and delivered both boat and men to the MacDill AFB boat dock where the injured sergeant could get medical assistance. Our Sunday "duty" day was now nearly over as we once more arrived at the Air Station, refueled and secured the picket boat. It had not been an unusual Sunday. It was 0400 hours Monday morning. We were almost glad that next week Section II would have Sunday with the duty. In a period of less than 24 hours we had provided assistance to 16 persons and five pleasure craft. I believe the tax payer got his money's worth that day. The Coast Guard may have changed how it operates the duty section rotation, but it still has many of the same responsibilities plus numerous new ones. I'll wager the individual Coast Guardsman still works the same long hours to insure all these responsibilities are each discharged with the same pride and professionalism with which they have always been. As a final note, that Sunday was one of my last with the duty in the Coast Guard. Several weeks after his rescue, the Air Force sergeant we'd hauled from the water took the time to come to the Air Station and thank us personally. He was in charge of the MacDill Air Force Base Recruiting/Reenlistment Office, and made me an offer that seemed, at the time, too good to refuse. That December when my enlistment expired, after nearly five years in the Coast Guard, I left to spend the next twenty-five years in the Air Force. The grass was as brown on that side of the fence . . . To learn everything you wanted to know about the repair and maintenance of aircraft engine spark plugs, check out the following pages from "Through the Overcast" by Assen Jordanoff, 1938: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5 Home & Index | Email Me! Copyright 2000 by Ted A. Morris

|