![]()

AN INTERVIEW WITH COMMANDER GEORGE EDWARD

MORRIS, JR.

REGARDING HIS EXPERIENCES IN WORLD WAR II

|

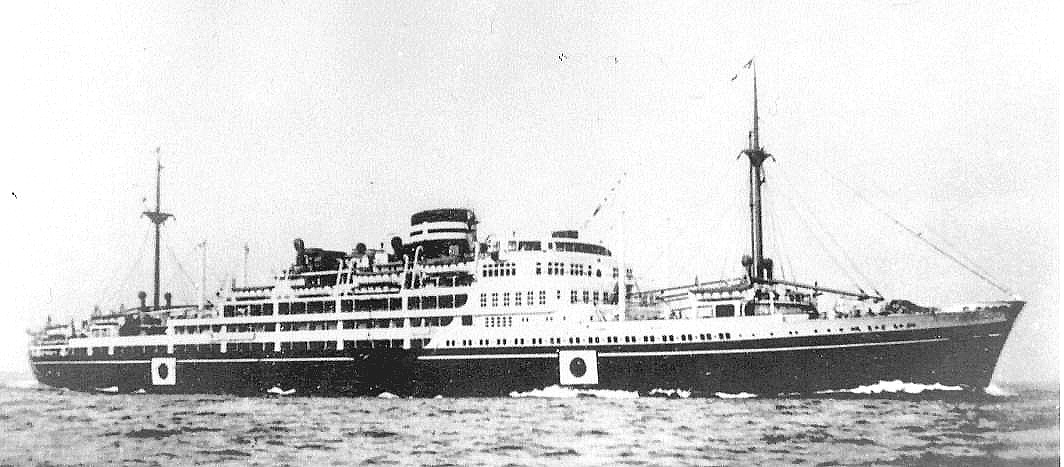

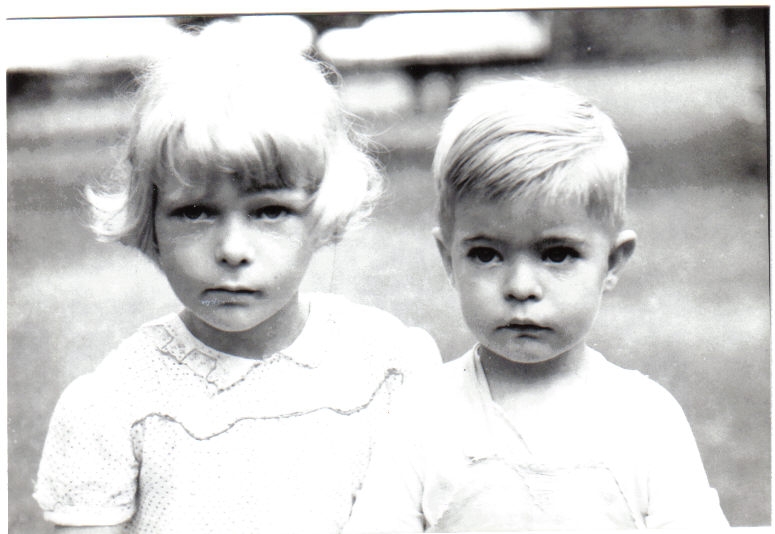

Editor's Notes: The following is a living-history interview with Commander George Edward Morris, Jr., known as "Ted" to his friends and family, concerning his experiences in World War Two. It was conducted by my father, Ted A. Morris, and myself, Ted A. Morris, Jr., on October 30, 1994 in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Uncle Ted was the brother of my father's father, Earl J. Morris. The interview was edited to eliminate the interviewers' questions, place details in their proper chronological order, and to make minor corrections for the sake of clarity. Otherwise, these are the words Uncle Ted.. He was born to George Edward Morris of Minnesota, and Isabel Mavor Scott of Inverness, Scotland on April 5, 1906, in Regina, Saskatchewan during a family stay in that area. The family returned to Minnesota, where Ted attained the rank of Eagle Scout in 1925 and graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1927 with a degree in Civil Engineering. He joined the U.S. Coast Survey after graduation, because, he said, "It paid twice as much ($2,000 per year) than any other job I could get." He was married December 26, 1932 to Katharine Elizabeth Schroeder of Washington D.C., who was known to friends and family as "Kay." Following several assignments, including peninsular Alaska, where he surveyed portions of the Inner Passage and Glacier Bay, he and his family were assigned to the Philippines in March, 1939. Their son Scott was born at Sternberg Hospital in Manila on November 19, 1941, the last American to be born there before the Japanese invasion. Kay and the children, Scott and three-year old Mary Ann, were captured by the Japanese in Manila. When Scott turned one-year old, they were interned in Santo Tomas Concentration Camp until liberated by American Forces in February, 1945. Kay's Story of internment by the Japanese follows this one. Click Here to go directly to it. Uncle Ted was captured by the Japanese on Corregidor when it fell on May 9, 1941, and was held as a prisoner of war in the Philippines, at Mojii, Japan, and Inchon, Korea. He was liberated by American forces in September of 1945 at Inchon. He was reunited with his family at Washington in November, 1945. After the war, he continued service in the Coast and Geodetic Survey, including a tour surveying the country of Liberia. He retired from the Survey in 1958, and taught college mathematics in St. Petersburg, Florida until 1974. He lived in St. Petersburg, Florida, until his death on November 7, 2003, and was a member of patriotic organizations including the National Order of the World Wars, and Sons of the American Revolution. In his later years he volunteered a great deal of his time at Bay Pines Veterans' Center in St. Petersburg. He is buried with his wife Kay in the Florida National Cemetary in Bushnell, Florida, Section 103, #898. DECEMBER 1941, MANILA Well, what would you like to hear first of all? I'm George E. Morris, Jr., and was a Lieutenant, Senior Grade, with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey out in the Philippines in December, 1941. When the war broke, I was Executive Officer of the ship "Research." There were two Coast Survey ships in the Philippines at the time, the "Fathomer" and the "Pathfinder." The "Research" originally was called the "Pathfinder," and it was built in '98 for Alaska. The Coast Survey built a newer ship they wanted to call "Pathfinder," so the old ship became the "Research." The "Research" was a two-masted sailing schooner. It had been built with the idea of operating in cold weather and had a big tumblehome. The only thing above the upper deck was the pilot house. Everything else was below decks. When I first went out to the islands in '29 and '30 the ship had been in the Philippines for some time, and the masts were still there and the booms were still in place. When I went back in '39, the booms had been replaced with strongbacks which were used for stretching awning over to keep the sun off the deck to make it a little cooler down below. It was a good-sized, steel-hulled ship; we had a crew of 80 men and nine officers. Except for myself, the commanding officer and the engineer, they were all Filipino. We had seven or eight Filipino cadets on the crew who were training to take over our operations when the Philippines gained its independence. We had an annual repair season for the ships when we completed minor repairs, and we were in Manila for winter repairs. We were at what was called Engineer Island, which had one of the best machine shops in the Philippines, run by the Philippine government. We'd haul out the ship, clean the bottom and make any hull repairs which were necessary. Principally, we'd complete any engine room repairs that required machine shop repairs that we couldn't handle aboard ship. There were five officers with the Coast Survey there in Manila at the time: Captain Cowie, Lieutenant Commanders Egner and Shaw, Lieutenant Junior Grade Stirni, and myself. Captain Cowie was killed in a bombing raid early in the war. The Coast Survey had the only copy of the nautical almanac in the Philippine Islands for the coming year, and Captain Cowie had made arrangements with the Philippine government printing office to duplicate this for the use of the Navy. The day he was killed, he wanted me to go with him to get these duplicates. We each had an official car and a driver. We got these cars by going into the car dealers and taking the cars and giving them a slip of paper for it. We used the cars to go running all over town doing different errands. I didn't see much use to the errands, though I suppose we were making a showing to the public that we were doing something. Anyway, I asked Captain Cowie, "What should I do with my car?" He said "Well, you'd better keep your car." And so I didn't go with him. They bombed the building that the printing room was in while he was in there, and he was killed. Lieutenant Commander Egner, as the ranking officer, then took charge of the Coast Survey there in the Philippines. When Egner moved up to director, I moved up to Commanding Officer of the "Research." Lieutenant Commander Charley Shaw was in Stotsenberg Hospital there in Manila. He had been down in Jolo and got tangled up with a native and cut up. Lieutenant Junior Grade Stirni was aboard the "Research." After Christmas, the Japanese began bombing Manila, and a small bomb hit the launch we had moored alongside the gangway of the "Research." The launch caught fire, but fortunately the standby crew aboard the Research was able to put the fire out, and the only damage was from where the fire had warped some of the side plates. We inspected very carefully below the waterline and could find no leaks. During the night after this bombing, I was at home in our apartment in Manila, and one of the crew members came and said that the Army had given them orders to take the ship out, either to Corregidor or into deep water and scuttle it. So I went down to the ship. We just had the nightwatch crew aboard at the time, about one third of the crew. We were under power from the pier, so we got up steam and I took the ship out and cruised slowly down Manila Bay waiting for daylight to cross over to Corregidor. Egner, Stirni, and of course Shaw stayed in Manila. Egner and Stirni were picked up as civilians and interned in Santo Tomas Concentration Camp. Some months later, probably about six months after the Japanese occupied Manila, the Japs discovered they had an Army Lieutenant in with the civilians in the prison, and they made a sweep to see if there were any other uniformed officers. Stirni didn't know what to do, so he looked for Egner to see whether he should report as an officer of the uniform service or stay as a civilian. Stirni couldn't find Egner, who was never much help to anybody, so he reported in and was taken up to Cabanatuan, but this was several months after the rest of us from Corregidor and Bataan were all up there. Egner stayed at Santo Tomas, and Charley Shaw was put in Bilibid prison. I saw Shaw when I was being transferred from Cabanatuan to Japan. He got back home after the war, but died, and Egner has died since. Stirni was killed when we got bombed in Taiwan. BATAAN AND CORREGIDOR, DECEMBER 1941 - MAY 1942 When the standby crew and I got the Research over to

Corregidor, we went in to an anchorage on the north

shore. You couldn't really call it a harbor where we

dropped the anchor. When it got light, I went ashore to

see the harbormaster to see where he wanted the ship

moored. Maybe I'd better digress here and explain about the barges. At the Manila end of the bay, they had built a big breakwater the ships could go inside. The piers were all built inside the breakwater and they all had odd numbers. Pier 1 was the Army pier used by the Quartermaster Corps. The open-U shaped piers 3 and 5 were used for commercial shipping. Pier 7 was the largest pier and could take a couple of the big ocean liners on either side. The other piers were smaller. Most of the ships visiting Manila would anchor inside behind the breakwater, and they had river barges to service those ships. The Pasig River did not open into this enclosed harbor area, but there was an opening through the breakwater into the river. The barges could go through this opening and upriver to the bodegas and warehouses along the river. So we, and when I say we, I mean the American Forces,

collared these barges. We'd take them to Pier 1 and load

them with Army supplies from the warehouse and whatever

we could gather in from Fort McKinley and Nichols Field,

which were close by. We'd load the barges, tow them

outside the breakwater and turn them loose. From the

river, the natural drift was out the bay. Corregidor was

at the mouth of the bay and we'd pick up the barges

there and ground them. Then we'd offload them onto

either Bataan or Corregidor depending on which side we

happened to ground them. The harbormaster on Corregidor wanted us to work at this job with the launches from the Research. So we struck this agreement, and I wrote this lengthy report about it to Washington. I went into Malinta Tunnel where they'd set up an office and borrowed a typewriter and typed my report as a letter, though whether it ever got to Washington I never heard. They were still running one of the ferry ships back and forth between Manila and Corregidor at night. That evening I left a few volunteers aboard our ship, and took most of the watch I had with me back to Manila. I figured to use them to round up the rest of the crew, as well as give these men a chance to see their families. I gave them the word to get the rest of the crew and be back at Pier 1 the following evening and we'd go back to Corregidor. I went back and saw my wife, Kay, and our children, and that was the last time I saw them until I saw her in Washington in November after the war ended. Well, the following evening I got down to the pier, and, no one from the crew showed up. So I went back to Corregidor alone on the ferry. One of the things they did on that night ferry was dispose of equipment they didn't want to fall into Japanese hands. The military had taken half a dozen three bushel baskets of parts and some of the control equipment from the electric power plant in Manila, and on the way back we set some boxes on the port side, and some on the starboard, and we threw pieces overboard all the way back so it would be impossible for the Japanese to retrieve them and repair the power plant to obtain full power. When I got back to Corregidor, I found my ship had sunk

from the pounding it had gotten and leaks we hadn't

discovered. She had grounded first on the Corregidor

shore, but with an incoming tide, she'd floated off back

into the bay and finally grounded a few miles up the

Bataan coast. One of our civilian employees, an old timer by the name of Maynard, was a Reserve Army Major in the Corps of Engineers, and we made a deal with the Army to move a printing press and keep making maps for the Army as they fell back into Bataan. We loaded it onto a barge in Manila to get it out. It got to Corregidor, but never got off the barge. They loaded the small press, and everything we needed including all the plates to make maps of the islands. We had the original plates for the area and the islands so if the submarines came in and needed charts, we could furnish them. But at the last minute some Air Force personnel came over to Corregidor to come down with a jeep to load on this barge. When the barge was grounded they sent a detail out to hoist the printing press up the cliff so we could get it into the mortar battery where we had set up shop. But instead of getting the printing press, the detail concentrated on getting that jeep out, because we didn't have much transportation on the island. So they spent all night getting that jeep up and the next day we got a higher tide coming in and the barge floated off and we never saw it again. The printing press and all the equipment went with it. We did have all the equipment to make blueprints, though. You just have to have a few chemicals and the paper. You expose it just like you would a negative, put it in a tube with some of the chemical and you get a blue print. So that's how we made our maps. I got the job of going over to Bataan and get the information on the new front lines and bringing it back to Corregidor, where we'd put it on the maps. At least once a week I'd go over to Bataan to get the information on the new lines, and carry a bunch of maps over. While over there, I'd stay with a major in the Quartermaster Corps or with a Lieutenant Colonel in the Army Air Corps, Nicky Amos. By the way, this Lieutenant Colonel was one of the five flyers who made the first non-stop crossing from San Francisco to Honolulu by air. Maynard set up our shop there on Corregidor in a 12

inch mortar battery. We cleaned all the powder out of

one wing of the battery and set up our processing and

drafting equipment, and our living quarters, cots and

that, in there. I don't know if you have seen one of

those mortar batteries, but there's a U shaped bunker on

one end and four great big mortars set behind walls that

were quite high, because mortars shoot almost straight

up in the air. The battery wasn't being used at the

time, though after Bataan fell, they reactivated it for

the month or so that Corregidor held on. Corregidor, looking down on it from the top, looks very

much like a scorpion. It has a big body and a long whip

tail. The big body is quite high, and that's where we

had our Bottomside, Middleside and Topside. Out on the

tail, there's a depression maybe 30 or 40 feet above sea

level, and then there's this big outcropping, Malinta

Hill. They'd tunneled all the way through that, with

laterals off either side, and they had one lateral that

went all the way out to the north shore. There was a

road around the north side. They had brought down the

gold miners from up at Benguay, in Northern Luzon, and

had built another tunnel parallel to Malinta tunnel, but

to the south of it. They called this tunnel Queen's

Tunnel, and the Navy took that over. I didn't have a whole lot to do until we got our set up in the bunker completed. I would spend time hither and yon, get a car every once in a while to go from here to there for some reason or the other, but I had no specific assigned duties other than the trips over to Bataan to get the information. The troops there were being pushed, but they had a steady fall back plan, and they had to coordinate it so they wouldn't leave flanks exposed. It was quite a long line all across that peninsula and they didn't want the Nips to come through and get behind anybody. We were getting most of our information about the war from a San Francisco short wave radio station. I remember some disc jockey on the station telling the Nips what they could do and what they couldn't do - that they couldn't bomb Corregidor, and that they wouldn't dare send a plane over Corregidor. Well, the next day was when we got plastered. That San Francisco station was telling the Japs what they couldn't do, and the next day, the Japs would go out and do it. We heard on the radio that our assistant director of the Coast and Geodetic Survey had transferred us to the Navy. My wife and I had lived with the second echelon, the majors and lieutenants, of the Philippine Department of the U.S. Army, and socialized with them for two years, and knew them quite well. Those men were now on Corregidor and on Bataan, and I talked with them about this development. After getting their ideas, I went to the Navy setup in Queens Tunnel, and talked with them. I said I thought that the Coast Survey had been transferred to the Navy, and was reporting to them for duty. The Navy people wanted to know if there was somewhere I was staying, and I told them, yes. When they learned where I was living and what we were doing with the map making, they said they would assign me as liaison between the Navy and the Army map service, and wanted me to report to them occasionally about what was going on. And that was it. They said communication with the United States was so spotty, and there was so much that they had to send, that they would let the actual transfer formalities be taken care of in the United States. But the assumption was that I had been transferred. They accepted it there on Corregidor, and all the way back to the States, that I was serving then in the Navy, as a Naval Officer. As I said, I had friends over in Bataan, including the Assistant Chief Quartermaster of the Philippine Department. See, they had the Department Command, commanded by MacArthur. Then they had the different units, the cavalry, the field artillery up at Stotsenberg, the Air Force at Nichols Field, and medical detachments with sub-chiefs and all that all over. My connections were with the Department people. That's how I wound up with the job of going over to Bataan and getting the new line demarcations and bringing them back to Corregidor. I had a few other jobs, like in our grenade factory. The grenades that we had were the World War I pineapple kind where you pull the pin and hold down the lever until you're ready to throw it. When you let go of the grenade a spring would throw that lever off, arming the grenade. Two or three seconds later it went off. Only these grenades didn't go off. Of course once you threw that grenade, you gave your position away. We were getting a lot of casualties, not from the grenade itself, but the after effect of the grenade not exploding. So we had boxes and boxes of practice grenades that were just the same weight but with no levers or anything. We took black powder and loaded them with that, and stuck a dynamite cap and a short fuse in the powder. We were issuing two packs of cigarettes a day per man at the time, and we made the men take the cellophane cover off the packs of cigarettes right then and there and give the cellophane to us. Then we would take two kitchen matches, of which we had a lot, put them with the grenades we'd made, and wrap them all up in the cellophane. When a troop wanted to throw a grenade, he'd unwrap it, had two matches to light the fuse, and then he could throw the grenade. We spent many an evening making grenades for the front line troops to use. Over on Bataan there was a little indentation called

Mariveles Harbor and the Public Health Service had a

quarantine station there before the war. The Navy pretty

much took that over. They had the USS Canopus in there

and they tied that up alongside on the south side of the

harbor and used that as a submarine tender. The

submarines coming in would tie up there for resupply,

getting more torpedoes and any machine work done that

they needed. We still had order then among the forces. We never

really lost order, even when we finally knew we were

defeated, when MacArthur left. SURRENDERED TO THE JAPANESE. BILIBID AND CABANATUAN, 1942 - 1944. Finally, Bataan fell. Most of the Navy people got across to Corregidor, but the others didn't. Corregidor held out another month. The surrender was a matter of food more than anything else. We were on the verge of not having any food. The only thing that disturbed me was they had a radio operator crying his eyes out over the short-wave radio on the surrender. He must have been just a kid, no control at all, hysterical on the air, right up until they had to destroy the equipment. Once we were prisoners we were taken out on this one strip of low sand there on Corregidor and left. The area of the ice plant and storage area was pretty badly shot up during the Japanese landing. We had a detail to go up to pick up food from there and carry it back for distribution. We also set up some lister bags for water and put iodine in for purification. We were there for several days. Finally we were loaded aboard some old freighters. When they built those freighters, there was a beam across the deck on which they took old welding rod and spelled out the name of the ship. The freighter that I got on I recognized as one of the Alaska Steamship freighters that went from Seattle up to Ketchikan, Juneau and that area. It had been sold to the Japanese for scrap iron about three years before the war started. When we got to Manila, instead of taking us and unloading us at one of the piers, they took us down the beach aways. They took us in small boats until it was knee deep water and then we waded ashore. Then we paraded down Dewey Boulevard, across the bridge into the Tando area and into Bilibid prison. They kept us in Bilibid for close to two months. From there I went to Cabanatuan in June of 1942, then in October or November of 1944 we were transferred back down to Bilibid and in early December we started our journey to Japan, which I'll tell about in a while.

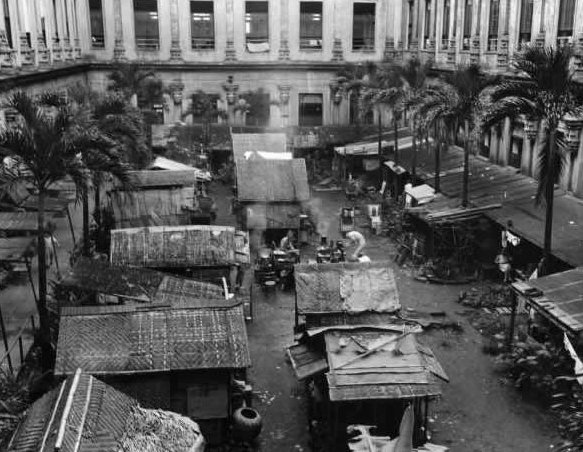

They took us from Bilibid to Cabanatuan by train. I was in Cabanatuan from early June 1942, in Camp Three. In the fall, we were transferred down to Camp One. Before the war, out west of the city of Cabanatuan in central Luzon, we'd built camps for the Philippine Army, which was a sort of National Guard. The Japanese used those camps for the Prisoners of War, and we stayed in the barracks built for the Philippine Army troops. The barracks were pretty short for Americans. The first level was about two feet off the ground, and the second level about four or five feet above that. You couldn't stand up straight in them; you were always stooped over. There were three camps at Cabanatuan, Camps One, Two and Three. The people from Bataan had been taken up to O'Donnell, which is more to the east of Cabanatuan. Eventually they had been transferred to Cabanatuan. I don't know whether they'd had any go to Camp number two or not, but the bulk of them had gone into Camp number one, those that had survived the Death March and O'Donnell. Of the prisoners from Corregidor, the first batch went up to Camp Two. The next batch, of which I was one, went to Camp Three, which was further out from the city, and not far from the woods. It was later in 1942, almost the end of the year, before all the prisoners were all consolidated into Camp One. By that time the majority of those from the Death March had died that were going to die. They had also taken details out and shipped them up to Japan and Korea, and taken out all the Filipinos so that we could all fit into Camp One. At first, Camp One was divided into three areas. The camp itself was alongside the highway, and divided into three laterals. The one toward town was called the hospital area where the really sick were kept. The middle was for the camp guards and Japanese personnel, and the other was for the rest of the prisoners. In the beginning, that was divided into three further areas. The Navy and Marines were in the one furthest from the road and the Army had the other two areas. As the Japanese took more details out and shipped them to Japan, they finally took the barriers out between the three divisions in the prisoner area. When we got established down in Camp One, most of the officers wouldn't work. The Japanese told us that it wasn't good to not do something. The mix of prisoners was such that the officers then had to work about half the time that the enlisted people did. Our jolly good camp commander, an American Marine, and his staff got busy and figured out that there were about as many field grade officers as there were company grade officers. Therefore, company grade officers would work every day, and the field grade officers wouldn't have to work, except when they called for extra-ordinary details. So I got to work every day. But I had the "in" because I started early. I volunteered to go to work from the very first time they asked for volunteers to take a detail out to go get wood. From then on I worked almost every day they had work details. I'd started with the wood detail. Our camp was at the edge of the woods and they'd send a detail out in the morning to cut wood. They'd cut branches and such, about three to six inches in diameter and about six feet long. Then I'd take a detail of about 100 men out twice a day to carry the wood back that had been cut. We went out just before noon and then in the evening. It wasn't much of a job, we didn't have to carry it very far. It was easy work. On most of the stuff, one of the Japanese, who didn't speak a word of English, would kind of sketch what he wanted, and I knew enough about engineering to know what he wanted. Like digging revetments. Ordinarily, especially toward the end, there were guard stations along the highway at both ends of camp. The Japanese put us to building revetments about three feet high around these guard stations. Some of the men took objection to building revetments, and I said, "Go on, if they get into the revetments when the planes come over, they'll get the whole bunch, rather than having them scattered all over." So we got the revetments built. I had details like that, usually small details. If we had over fifty men, I'd have somebody at the tag end to help keep them in order. We had a garden area where we grew some food, but I didn't go on too many garden details. I got the specialized details. Like one diverting a stream. There was a stream that went by, and they figured that by running some laterals they could divert some water into a little pond they had by the garden. We grew a plant that looked like cucumber. We'd pick them green and chop them up and put them into stew made with salt and water and we'd have it in our mess every once in a while. Occasionally, we'd see one of these "cucumbers" they'd miss under a leaf and had gotten ripe, and it tasted more like a cantaloupe or musk melon. We'd water those plants during the dry spells, carrying water to them from the pond. One day I took a small detail out, maybe ten men, to clean out a section of this ditch that they had dug. We didn't have to grow our own food; the Japanese bought it. Rice mostly. But in addition to the "cucumbers," we grew string beans. One day we went out to pick the string beans. We brought them in and turned them over to the Japanese, and that was the last we saw of the string beans. The next day we went out and picked the leaves, and that day we had bean leaves in our mess. I don't know whether the Japs ate the beans, or whether they took them into town and sold them to get rice. One of the last things we did at Cabanatuan was go just

outside of camp in the rice paddies and cut down all the

dikes and the ant hills and make an airfield. Now alot

of the people objected to doing work like that, but my

attitude was that we should work and do enough to

satisfy them. One punishment they'd give was make two people to stand

up to each other and slap each other. If they didn't

slap hard enough, the guard would take one of them and

say whatever he would say to him in Japanese, and them

slap him hard enough to almost take him off his feet. On

the detail where we were cleaning out the ditch leading

to the pond, a couple of our men got to goofing off, and

the guards made them stand up and slap each other. We were always low on food, and there were periods when the Japs were pretty low on food, too. As I said, their quarters were in between the hospital group and our group. Usually you'd see a bunch of G.I.s lined up along the fence waiting to clean the Japanese cooking pots. They'd wash the pots so they could get the scrapings. But once in a while it would be the other way around. The Japanese would be lined up to clean the American pots because we had more scrapings than they did. Clothing was in short supply, too. Basically, we had what we were captured with. For the work details I cut the legs off of some trousers and had the tailor make me a G-string out of the legs. That's what I wore all day long. I had one pair of shoes the whole war. I made others out of two by fours with a strap across the instep. We didn't have many problems with bugs in camp. There weren't too many mosquitoes around, though the bed bugs were pretty bad at times. We'd get boiling water from the galley and pour it on their hiding places. For my sleeping arrangements, I got a couple two by fours and a half a pup tent and made myself a bunk. I got a hold of an Army raincoat, which was pretty stiff, and I elevated my bunk up a couple feet off the deck, and I had a mosquito net. It was in the winter, and getting a little chilly. It was getting uncomfortable, but I hated to get out of my bunk and get something to put over me. Finally I decided I'd get out and get that raincoat, and it wasn't too long before I started to warm up and felt comfortable. Well, come morning and time to get up, I looked and my raincoat was still hanging on the nail! Psychological I guess. In the beginning, there were Regular Japanese troops guarding us. One of them had this American flag he got and one day, he washed it and hung it on the barbed wire fence outside their compound to dry. So I had the detail coming back with the wood, and I called them to attention and "Eyes Left." Nothing was ever said to me or anybody, but the flag never showed up again. Now, in Japan and sometimes in Korea, the camp

commandant would form up the prisoners and make a

speech, but not very often in the Philippines. I don't know how long they'd been doing it, but they had an experiment going on, trying to cross Brahma bulls with the local water buffaloes, the carabaos. They were trying to produce a better beef producing animal. We had about twenty of those bulls in camp, and the veterinarians were assigned to take care of them. Now, at threshing time we go gather up the rice straw and bring it back to feed the bulls. Well, they'd call out everybody, even some of the Lieutenant Colonels had to go out on the detail. Everybody except the sick. Well, rank had its privileges, so one of the Lieutenant Colonels, or a Major at least, would be in charge of the detail. When we got to the rice paddies, we got to rest. We

were supposed sit there braiding grass into a rope to

tie up our bundle of straw. The guards were sitting

around with us, and I was sitting with some of the

guards I'd been out with on details for years. I knew

them quite well. The guards kept saying what terrible rifles the Enfields were, and I was talking them up, saying they were good rifles. No, it's a terrible rifle they kept saying. So I said, "If its such a terrible rifle, why don't you sell it to me." So this one guard says, "O.K., how much?" and I said "One peso." I took out a peso and he said O.K. I gave him the peso and he gave me the rifle. There were half a dozen guards around there, and they

almost had hissies. They were afraid one of their

officers would see this. They kept telling him "Get that

rifle back! Get that rifle back!" So I said, "Well, this

is a pretty good rifle, you know, but I'll sell it to

you. For two pesos." He said, "But I don't have two

pesos!" This went on for a little while, and I finally

said, "Well, you're a good friend of mine, so I'll sell

it to you for one peso." We did get paid in prison camp, by the Japanese. I was paid what a Captain in the Japanese Army would get. They paid us in occupation script, and I always got more money than I could spend. When we were in the Philippines we could buy things. The Filipino merchants would come to the gate, and our camp quartermaster corps would get what they could. The merchants operated as fair a deal as was possible. The quartermaster corps had a representative from each barracks take orders on things we needed. You had to put the cash down with the order. Suppose you wanted half a dozen eggs, you'd pay for half a dozen eggs. But there wasn't that much to buy, so when your order came in you might only get one, or maybe two eggs, but you did get your money back. I always had more money than I could spend, so I'd find a G.I. who wasn't getting much money and pay him to do my laundry. That gave him a chance to get more than he could buy with the little money he was getting, which was what a Japanese private was making. I also learned to shave with a straight razor. We had a fellow who was a barber and he set up a barber shop. You could pay him to shave you or get a hair cut, but he also had a razor you could use without paying. When we got to Japan and Korea, I used a razor blade to shave with. Once every other week, we got a pair of clippers to cut each others hair. We didn't have to shave our heads, but we had to keep it short. Once we got established in Japan, there wasn't much to buy. You couldn't buy anything to eat. I think I bought a couple of razor blades and a pencil, but I wasn't allowed to keep a knife to sharpen the pencil. In Korea there was nothing to buy at all. The Japanese came out and said, "There's nothing for sale, so we'll hold your money for you." The first thing the Japanese paymaster did when the war ended was pay us that back pay, of course it was worthless occupation script. We had some entertainment in camp. We had a group of prisoners who put on theatrical presentations. Some of those plays they had gotten themselves, or they were ones the Japanese had picked up from the theaters. The prisoners practiced all week and then on Friday or Saturday night they'd put on the play. We had a few musical instruments, too. They got to be pretty good. We did get Red Cross packages occasionally. The first Christmas, 1942, when we were in Camp One, we got a Red Cross package apiece. We still had a bunch of the sick from the Death March the previous April, and were having burial details every day. I don't know whether it was Christmas or New Year's Day, but that was the first day we didn't have a burial. But on that Christmas, we had half a dozen men who sat down and ate their whole Red Cross package, and died. A Red Cross package contained a pound or fifteen ounces of raisins or prunes. It had either a twelve ounce can of corned beef or salmon. It had a chocolate bar and two packages of cigarettes. And it had something that was put out by a tile company that was an oatmeal concoction that you could eat like a cracker or mix up with water and have a dish of oatmeal. It was about the size of a four-ounce tuna fish can. That was about it. It wasn't a whole lot to kill somebody, but we hadn't had much food, and when you're in that condition, you can't stuff yourself too much. We knew we weren't going to get the Red Cross packages very often. When we got to Japan and Korea we got one package for every two men every two weeks or so. In Korea we had to turn in the empty cans to prevent stockpiling food for an escape. We left Cabanatuan in October or November 1944. About a month before we left we started seeing planes off in the distance. Since I worked almost every day, I saw the planes often. Some of the guards would ask, "American?" and I would say, "Oh, we,don't have any planes, they must be Japanese planes." There were so many planes, but they were so thick at the distance we just couldn't identify them. We'd be out on these details in several trucks. We were packed in tightly, pretty much standing up in the trucks. Nobody could fall down. Every time we'd see planes off in the distance, we'd stop under the nearest tree. We'd pass by the cemetery at Del Norte on these details. Halloween at cemetery Del Norte was quite a sight. That was when the Filipinos would decorate all the mausoleums and light them up like Christmas trees. But when we'd go by in the daytime, we could see the drums of aviation gasoline stacked around all the mausoleums in the cemetery. This was where the Japanese were hiding their gas. THE HELL SHIPS, 1944. In 1944 they moved us by truck down from Cabanatuan to

Bilibid in Manila, in preparation for transport to

Japan. Finally one night we were told we were going to

move out in the morning, and about four in the morning

we all lined up four abreast. About seven o'clock they

issued us rice balls of cooked rice about the size of a

softball. Then along about nine or so they marched us

down to Pier Seven. Fortunately there were water spigots

on the pier and we could have all the water we wanted to

drink. As I stood on the pier, I counted about twenty

ships that had been sunk in the harbor. They had double decked the holds so we had a space about three feet high. From the skin of the ship to the partitions was also about three feet, and we sat as close together as we could. I was about four or five from the end of the isle in, with my back to the outer skin of the ship. They got water down to us just before dark. During the night we left. We found out later we were in a convoy with four freighters. It was kind of hard to tell what time it was, but it was daylight the next morning when we were bombed. I think it was by dive bombers, and they sank the four freighters. The planes strafed the ORYOKU MARU. There was a quadrapod over the front hold, and they had a machine gun on top of that. I guess it was an anti-aircraft mount. Anyway, the blood from the gunners up there was dripping down into the hold. The planes would shoot one off, and another would take his place. They took what Doctors we had up there to take care of the injured. They had loaded a lot of sailors and civilians aboard to take back to Japan, and they were up in the cabins. In the strafing a lot were wounded. So they took our medical personnel up to take care of them.

During the night the ship ran into Subic Bay, and they

took all the Japanese off during the night. The next

morning three planes came over and they dropped bombs on

the ship. One bomb hit in the amidships hold, and one

bomb hit in the aft hold. Then the Japanese guards told

us to swim ashore. When we got out of the hold, the

first thing I did was look around for something to eat.

There were pantries there, but there wasn't any food. There was a doubles tennis court there at the Marine Barracks, with a chicken wire fence around it. They put us in there, and there was a water spigot in there. There weren't too many people left, and we had room to lie down. A lot of them headed for the tennis court itself, but I took the dirt area alongside where I could dig a hole for my hip. We were there for a couple days, and didn't have anything to eat. We asked for food, and the Japanese said, "Your food is on the ship." They didn't have any either, and they'd had to send to Manila for it. Finally they got a sack of rice, I guess about a hundred kilo sack. It was a good sized sack, anyway. Someone had saved an empty preserved butter can out of a Red Cross package. It was called preserved butter, but it was more like cheese. It was about the same size as a four ounce tuna can. They measured out one can of raw rice a day for our ration. That was all. We just ate it raw. Grind it with your teeth and swallow it. And drink plenty of water. During the day they'd let us go outside where we could sit around. We had several wounded, some of them quite severely. The senior officer was a Marine Lieutenant Colonel, and of course his staff was all Marines. No Navy, no Army Air Force, no Army. His interpreter told the Japs that, "These men ought to go back to Manila to the hospital," that they couldn't travel. The Japanese finally agreed that they'd get a truck and take them back. The Marine got one of his Majors, who was slightly wounded, but not badly, and briefed him on what he would do when he got back to Bilibid, what complaints to make and all that. Well, we found out after the war was over that the Japanese took the whole bunch out and shot them and buried them in a mass grave. They hardly got out of gunshot range of us. There was a whole truckload of them. Finally, they took us by truck to San Fernando in Papanga, which is on the railroad. They put some of us in a theater where they had taken the seats out, and the others into a school house somewhere. Now I had been eating in a fixed mess the whole time I was on Corregidor, so I had no mess gear at all. I had no canteen. So I scouted around and I found a one-liter oil can. Someone had a knife and I cut the lid out of it. There was a lot of water, there was a spigot in the theater, and I cleaned that can out. I carried that can with me all the way to Japan. That was my canteen, so when we got water, that was my container. We were in the theater two or three days and they furnished us rice balls with some greens mixed up in it. Some sort of cabbage or lettuce. They were fair sized rice balls, and we got one a day. Finally, they marched us down to the railroad station and loaded us into boxcars. They had the narrow gauge railroad and the forty and eight type boxcars. We counted and we had 126 men in our boxcar, and about 30 on the roof. We finally got started, and it got hot. The ones by the door were pretty lucky, and the ones on the roof were very lucky. I don't know what they were using for fuel, but when we came to a steep grade, it was all the train could do to make the grade. You almost had to get out and push. Well, at night, the ones on the roof were freezing, while we on the inside, as far as temperature was concerned, weren't too uncomfortable. We finally reached San Fernando la Union, up on the Lingayen Gulf. They put us on the beach. It was about a quarter of a mile from the nearest water spigot. Somewhere they got a couple of water buckets, about twelve quart pails, and we started a bucket brigade. The Japanese had us form up in groups of twenty, and get the water ration from those pails. I drew the water for twenty people. We lined up our containers in a line, and kept the same line-up every time we got water. I had a spoon, and spoon by spoon I would go through the line passing out water. I'd remember where I stopped and start there the next time we got water. We did that for two or three days. Then we were loaded aboard freighters. There were three freighters, I forget the names now. They had brought horses down in the one we had, and the hold was just filled with flies. But we had room to stretch out and there were some two by fours, and we laid them out across the ship to demark bays so we could lie down. I don't remember just how long it was before we upped anchor and went up to a harbor on the South end of the Island of Formosa. [Note: Based on the following events, this ship was the ENOURA MARU] Our ship tied up alongside another ship. I found out

later it was about a 5,000 ton oil tanker. We were

getting the water ration the second day or so when they

sounded the air alarm. People were scurrying all around.

I had the water bucket and I told them to calm down,

that I didn't want to spill the water. I was holding the

bucket up against my chest. It was full, I'd just drawn

the water and hadn't distributed it yet. Well, a bomb

went off... They had opened the holds so there wasn't any flooring over the holds, but the center I-beam was there, and the concussion dropped that I-beam on about fifteen of our men and killed them. The ones over by the side where the bomb had hit, it killed practically all of them. Lieutenant j.g. Stirni was one of them. A slug about the size of a silver dollar hit my bucket of water and put a hole in it about an inch from the bottom of the can. I looked down there, and I didn't have a drop of water in the bucket. That was my first thought, "I've lost all that water!" My whole thoughts were that I had lost all that water. I had a black and blue spot on the front of me that lasted well after we were up in Japan. But if I hadn't had that bucket of water, that slug would have gone right through me. All over my arms were little gouges where hot metal had hit me. One took a big chunk out, and it took years before it filled up. I didn't bleed any, but the joke afterwards was that that must have been a mean smallpox vaccination. The ship we were on didn't sink, but it was damaged, so the next day they moved us over to another ship [Note: Based on the events, this was the BRAZIL MARU]. Some other prisoners had loaded aboard that ship in Lingayan and they consolidated us all in that ship. One of the men on that ship was an Infantry Lieutenant I had met down in Zamboanga. We were basing out of there the last year before the war, and Kay had come down to Zamboanga, and we'd met in that social life among the military and some civilians who were on rubber plantations in the area. So we knew each other. He was with some of the others who had gotten down into the lower hold of the ship, where they were carrying raw sugar. Some of the more enterprising ones who'd been on that ship had gotten some of that raw sugar. Of course they had no containers to put it in.

Well, when we got on the ship, we weren't organized or anything, and I had put my gear down with some of the others on a hatch cover. The Japanese called for a detail to go back on the ship we'd just come from for a burial detail to take the bodies out to this Chinese cemetery for cremation. The Lieutenant had been picked along with some others, and when he saw me, he said, "Take care of my gear." Well, the first thing you know, I had gear from about six or seven people to look after. Then the Japanese wanted to take that hatch cover off and take the sugar out of the hold. The guards started yelling to get that gear out of the way, and I started picking it up. Out of one of these bundles of gear fell a dirty handkerchief with about two tablespoons of raw sugar in it. Now, I had a Navy Warrant Officer with me who was helping me move the gear. Well, the next thing you know, this Navy Warrant Officer and I were up on deck accused of stealing sugar. The interpreter kept asking me, "Why did you do this? Why did you do this?" I said I didn't do it. They asked who did, and I said, "I don't know." We were there for hours. Finally I convinced them the Warrant Officer was just helping me move the gear, and they let the Warrant eat the sugar and go down below! But they still held me up there. Finally I asked, "How could I have stolen the sugar when I just came aboard the ship?" Of course they knew the sugar had been stolen before that. But they kept asking, "But why did you steal the sugar?" I'd been standing the whole time. Finally the interpreter stood up and slapped me a couple times, not too hard, and told me to go. I saw this incident written up in somebody's story years later, and I'm sure it was the same incident, because I know there weren't two of them. The story went that some Navy Lieutenant had taken the blame for stealing the sugar to get the rest of them off the hook. But I wasn't as noble as the story gives me credit for. I was insisting that I couldn't have stolen the sugar because I wasn't there. You know, that little bit of raw sugar meant a lot. It’s been my experience that you don't mind a little dirt when you're hungry, and there're very few people who have really been hungry. We were. When the war started I weighed about 150 pounds. When we landed in Mojii, we were put in a bodega along the pier there, and there was a scale there and I weighed 96 pounds. The trip from Manila to Mojii was pretty uncomfortable. It was hot in the daytime, and then it started to cool down when we got to Taiwan. Now I kept track, because we still had the 20-man ration system. On the trip from Formosa to Japan, on some days we didn't get water, and on some days we didn't get rice, and we never got both on the same day. I kept track of the water because I dished it out, and it measured out to six ounces a day per man, when we got it. And the rice, well, if you were to put the rice in a coffee cup and not pack it down, it would come up about two inches. That was it. Like I said, over 1,600 of us got on the ORYOKU MARU in Manila. Fewer than 500 of us got out of that last ship at Mojii. MOJII, JAPAN AND INCHON, KOREA, 1944 -1945. We stayed in Japan until April, 1945. We were scheduled to go to Korea. When we arrived in Mojii, the guards to take us to Korea were there waiting for us, and when they saw us, they wouldn't accept us because we were in such bad physical shape. So they put us in a camp in Japan. We just laid around. The trouble with the camp in Japan was the way the barracks were constructed. They dug into the ground about two or three feet, and put mat flooring over it. There was an aisle down the middle, and the roof was pitched so that a man could just walk down the aisle standing up. In the winter time the ground was cold, it hadn't thawed out. They'd issued us overcoats on the way to Japan. They had three kinds of overcoats, all captured, of course. They had Australian coats, American coats and Dutch. If you were lucky you got an Australian coat, if you were not so lucky, you got an American coat. If you had no luck at all, you got a Dutch one. That was because of the cut and the wool content. The American coat was cut nice, but wasn't anywhere up to the standards of the Australian coat for warmth. I got an American coat. On the 23rd of March, the first day of spring, with snow on the ground, we had to turn in our overcoats! "First day of spring, turn in your overcoats!" We didn't have any blankets or anything, and the only other thing we had was what we brought with us from the Philippines. By that time that meant pretty much just the clothes on your back. We had gotten some clothing in the Philippines, but essentially I was wearing what I had when I was captured. I didn't see any of the bombing raids in Japan. In Korea we had big pits, like you'd dig for the basement of a house, with matting over the top, and at the first sign of a raid, we'd go into those pits. By the time we were in Korea, the guards were Japanese. When we were in Korea we had to work for our food. We had the jobs of making some very flimsy khaki jackets. We had to make four button holes and put four buttons on. We had to use like six threads per hole, and so many threads per button. Now some of the fellows would double up on the threads on the buttons so they were too thick. We had a two wheeled cart to take the finished garments up the street away and pick up the load for the next day. If we were assigned to the cart, we didn't have to do the sewing, and if we did the sewing, we didn't have to pull the cart. And that was about all we were fit to do. After the war, we waited about a month before the Americans got to us. We had a compound, a pretty big building, that we lived in. There was an area a little bit bigger than the building beside it and in that open place we had a garden. There was a path around the inside of the fence, which was about eight foot high, and the Japanese guards would walk around this path. One day we were called into assembly outside, and the commandant of the camp said that the war was over, and that they would protect us until our people got there to get us. So after that the guards walked around the perimeter on the outside of the fence instead of the inside. We learned later that if the Russians had come into Korea for us, we would have been executed by the Japanese before they got there. Once we were taken by the Japanese with some guards up a hill someplace to see a shrine or something as a sightseeing trip. There were two outfits of B-29s, I don't know where they were from, that dropped us supplies. You could tell they were two different outfits by the markings on the planes. They'd take two 53-gallon drums and knock the head out of one and the bottom out of another, fill them with stuff they thought we could use, welded them together and parachute them to us. We'd go out, and take the Japanese guards out with us to pick up what they dropped to us. I guess they had no idea how many men that we had in camp, but they must have thought it more than the hundred that were there. Less than a hundred. Anyway, one load was 156 gallons of chewing gum! I still have some clothing that was my share of what they dropped, that I've never worn. The one thing that they never dropped that I would have liked was milk. We never got any of that. Like I said, the first thing the Japanese did after the war ended was give us our back pay in occupation script. After we got paid, we went out with two of the Japanese and bought a bull, so we had meat. LIBERATION, SEPTEMBER 1945. Finally the Seventh Fleet came in to Inchon, and they decided to make a practice landing to get the troops off the ship to stretch their legs. Of course, I don't know how long they'd been at sea. Well, we were at the beach to meet them. We were first taken out to a Navy Hospital ship with a big Red Cross painted on the side, and our bags were all sprayed with de-lousing spray, and we were sent to the shower and de-loused, and put on clean clothes. We spent the night aboard the hospital ship. Then the next day we were transferred to a troop transport ship. Then we were transferred back to the hospital ship. Then finally they decided we'd go back on the troop ship. So we were released from the fleet, and we went down to Manila. They had a bunch of officers on board. We were practically all officers by this time, you see, because all the enlisted personnel had been shipped out of the Philippines early. We had company grade officers mostly, though we did have three or four Lieutenant Colonels and several Majors with us. By this time I was pretty much one of the senior officers. So I palled up with a graduate of Penn State who was an Army Engineer Captain at the time, and we ate at the second officers' mess. They said we could have seconds to eat if we wanted, but the mess stewards didn't think we should have seconds, and were nowhere to be seen when we wanted seconds. So Gil and I decided we'd do something about that. So we went down to the enlisted men's mess for our second helpings. And of course, as you'd leave the mess there was a box of apples or a box of oranges and you could take one with you. They'd opened a small store so we could get candy bars in the middle of the morning. Same thing in the afternoon and in the middle of the night. They couldn't make ice cream fast enough to give us every day, but we got ice cream every other day. In the 29 days between when we were picked up and got to Manila I put on thirty pounds. RETURN TO THE USA, NOVEMBER 1945. I flew back to the states from there on a PBM gull-winged seaplane. Every place we stopped there was a Red Cross person there breaking out the gear and we could have anything we wanted. Now Kay had it different. She came back to the States in February or March of 1945 on the USS CAPPS, which was manned with a Coast Guard crew. When she got to Leyte, she didn't have any shoes or money. I don't know how she bought her shoes because the Red Cross wouldn't give her any. From then on she was after me every time I mentioned the Red Cross. She didn't like it at all. When we got to Honolulu, they got us down to the airport pretty early. I was with a Navy Warrant that I'd been through the camps with, and we got the Red Cross busy cutting us slices of pineapple. We ate more pineapple. In the States, they put us in a hospital in Sacramento. When it came to mealtime, they'd bring us just a little skimpy portion of whatever it was, and we asked, "What's this?" And the nurse said you can't eat too much food, you can't rush things. I just couldn't convince her that she was thirty pounds too late. They only kept us there a couple days and then we flew back to Washington. I had a big parade in my honor: Kay, Mary Ann, and Scott came to meet me. I was still attached to the hospital out in Bethesda, and they wanted me to go to work getting ready to go take command of the Tampa office. I was working in the office for two or three weeks before I was discharged from the Naval Hospital. I got four years back pay. I took what they gave me and signed for what I got. When I was Chief of Party, and was paying the men on the Party, I had to be darned careful about the money, and I figured that I didn't have to worry about how much I got paid. Whoever had to pay out that money had to be just as careful about it as I was. When you're dispensing government money you don't make mistakes, at the level I worked at. Or you didn't in those days, anyway. I think Kay got paid a dollar a day for the time she was in the camp. Some years ago I got from our director the Coast Survey Asiatic Service Medal and one other, but they were both service medals. So I wrote and asked about the Bronze Star, the P.O.W. Medal and the Purple Heart, which I believed I was eligible for. I got back quite a pile of letters showing my service. One of the letters said that enclosed was the Purple Heart and the Certificate. Now this was the first I'd ever heard of the letter or the award. I certainly never received it. I still have not received the medal or certificate. Then there was something dated in the forties from someone connected with the War Department in some way saying I was not eligible for the Prisoner of War Medal nor the Bronze Star, but I'd never received that letter either. They based that decision on the fact that I had never been officially transferred to the Navy. I had reported for duty and was accepted on the local level on Corregidor, but that's where it started and ended. I was considered an officer of the Navy all during the war and on the way home. I was recognized by both the Americans and the Japanese as being an officer of the Navy. For example, as far as I know, the civilians were never put on work details, although we had civilians in, and to my knowledge, no civilian was taken from our camp and sent to Japan, Korea or Manchuria. Even after I'd gotten back, until I was discharged from Bethesda Naval Hospital. But on the record, I'd gotten all my back pay from the Coast Survey. When I was in about the third grade in Minneapolis, I started saving money. The Farmers and Mechanics bank in Minneapolis started a program where every other week or maybe once a month you could bring in your pennies and get savings stamps. When you had a dollar worth of stamps, you could turn them in and get a dollar, or start a savings account. So I started a savings account when I was in third grade. I kept that up, and by the time I was in the Philippines I had about $5,000 in that account. Kay used my passbook with Chinese merchants in Manila and forged my name on the withdrawal forms. Kay was allowed to stay out of Santo Tomas until November of 1942, when Scott turned one year old, and she used the money to buy food and supplies during that time, and to stock up with things to take inside when she went in. I guess she also used the money to buy things when she was inside the camp. She established a friendship with some of those people, and kept in touch with them after the war, though of course I never knew any of them. I was back maybe six months or so when I got a letter from the bank asking about Kay's draft, which the merchant had sent in for payment, and I said go ahead and honor it. What do I think of the Japanese? Well, if history is correct, an American who was pretty well known in his time used to say, "War is Hell." I agree. If the price differential didn't enter into it, I'd own a Honda, rather than a Hyundai. Do I ever see any of my fellow prisoners? Yes. There's one I correspond with at Christmas time, Gilbert Radcliff, up in York Pennsylvania. He's a retired Colonel in the Army Engineers. He was a captain in prison camp, and a graduate of Penn State. He wrote me a couple of years ago and wanted me to tell him about that sugar incident, but I never have. Maybe this will do it. How long did it take me to get back in the swing of

things after I got back to the States? A couple of days.

I can't remember ever getting stressed.

MY EXPERIENCES IN

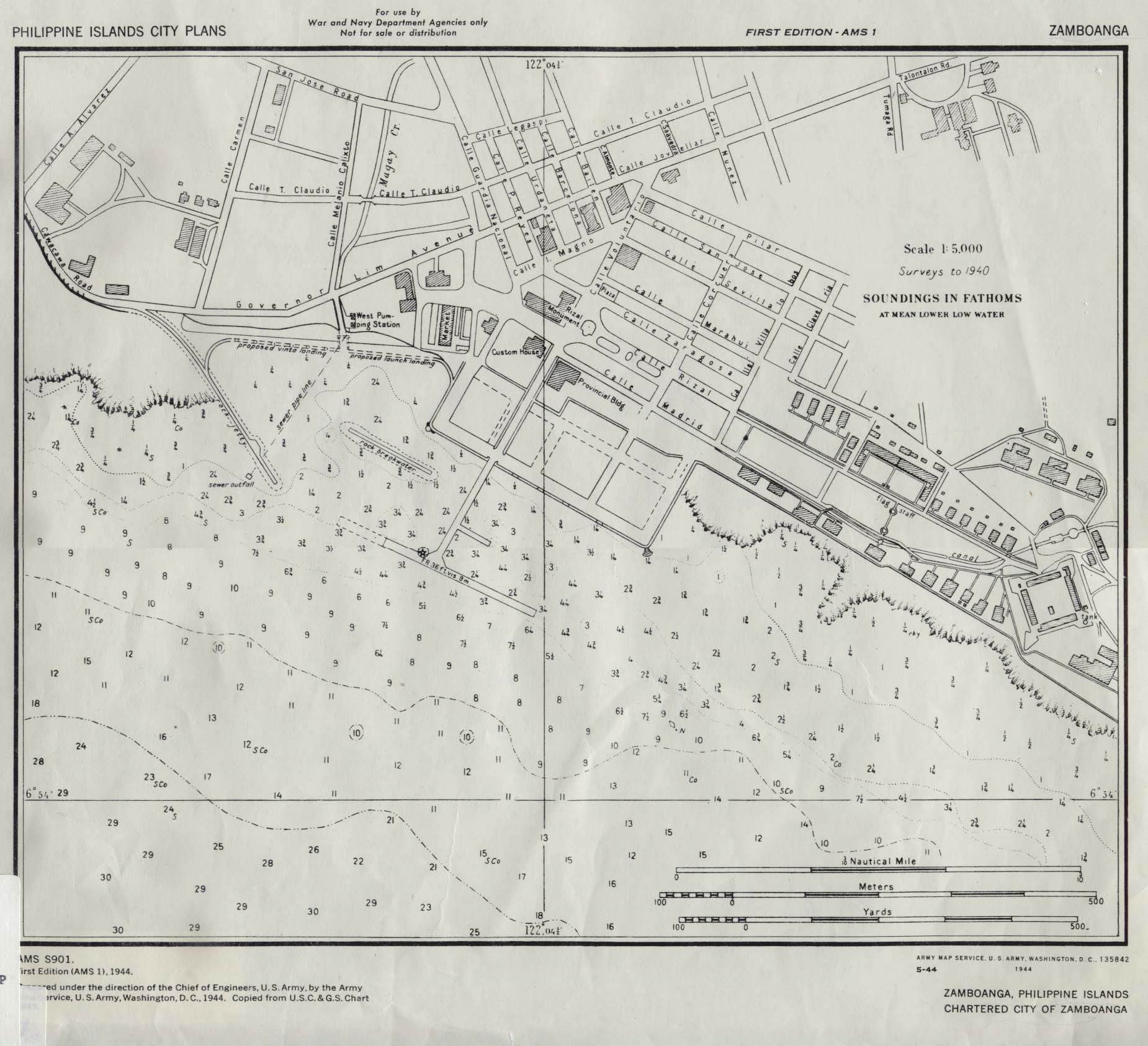

WORLD WAR II Editor's Notes: My Great-Aunt Katharine "Kay" Elizabeth Schroeder Morris was born in Washinton D.C. in 1909. Her father was the President of the First National Bank of Washingon, and Kay was extremely well educated, earning a Master's Degree in Education. She married George Edward "Ted" Morris, Jr., on December 26, 1932, and traveled the world with him. She was an avid collector of native art during their travels, and upon Ted's death in 2003, her collection was donated to the Smithsonian Museum. She researched her family geneology, and was active in the Daughters of the American Revolution throughout her life. She died in at her home in St. Petersburg, Florida, October 29, 1988. She is buried at the Florida National Cemetary in Bushnell, Florida, Section 103, #898, along with her husband. In the early 1990's, my Great-Uncle Ted, Kay's husband, gave me a carbon copy of the text of an interview Kay gave to someone (name unknown). The only changes I have made were to reorganize the text into chronological order, and make some minor spelling and grammatical corrections. Otherwise, these are the Kay's words; she was very well spoken, with a rich and precise accent from the old South. As of this writing, in February 2008, both Mary Ann and Scott are alive and well, living in Florida and Oklahoma respectively. TAM,Jr ZAMBOANGA, SPRING AND SUMMER, 1941. Early in the spring of 1941, my 2-year old daughter Mary Ann, Ah Lai, our Chinese amah, and I arrived in Zamboanga from Manila on a small inter-island steamer. My husband Ted (George Edward Morris, Jr.) was in the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (USC&GS), and his ship would be basing there until fall. We had our reservations at the old Plaza Hotel on the town square. The hotel was a large two story building of stone, with shops and bodegas (warehouses) on the ground floor. The second floor had the dining room, kitchen and bedrooms. There was a wide balcony surrounding the upper story. Zamboanga was a peaceful and beautiful provincial town on the southwest coast of Mindanao Island in the Philippines, then part of the United States. I enjoyed sitting and talking with Mrs. Cooley, who had a souvenir shop on the ground floor of the hotel. She designed and made beautiful silver things in Moro and other unusual designs. She also used black coral to make bracelets and handles for serving pieces and I still have a few pieces of her work. There were also a few Chinese shops and Filipino tiendas (stores) around the beautiful old Catholic Church in the Plaza, as well as a rather ramshackle building where Chinese and Filipino movies were sometimes shown.

|