SCENERY OF BASHAN.

With the first dawn of the new morning I went up to the flat roof of Sheikh Assad’s house. The house is in the highest part of the town, and commands a wide view of the northern section of the mountain range and of the surrounding plain. The sky was cloudless, and of that deep dark blue which one never sees in this land of clouds and haze. The rain of the preceding day had cleared the atmosphere, and rendered it transparent as crystal. The sun was not yet up, but his beams shed a rich glow over the whole eastern sky, making it gleam like burnished gold, and throwing out into bold relief a ridge of wood-clad peaks that here shut in the view. From the base of the mountain on the north, a smooth plain, already green with young grass, extended away beyond the range of vision, dotted here and there with conical tells, on whose tops were the remains of ancient fortresses and villages. But on the west lay the objects of chief interest; the wide-spread rock-fields of Argob, the rich pasture-lands of Bashan encircling them, and running away in one unbroken expanse to the base of Hermon. Long and intently did my eyes dwell on that magnificent landscape. Now, the strange old cities rivetted my attention, rising up in gloomy grandeur from the sea of rocks. Now the great square towers and castellated heights and tells along the rugged border of Argob were minutely examined by the help of a powerful glass; and now the eye wandered eagerly over the plain beyond, noting one, and another, and another of those dark cities that stud it so thickly. On the western horizon rose Hermon, a spotless pyramid of snow; and from it, northward, ran the serried, snow-capped ridge of "Lebanon toward the sun-rising" (Josh. 13:5). As I looked on that western barrier of Bashan, the first sunbeams touched the crest of Hermon; and as they touched it, its icy crown glistened like polished steel, reminding me how strikingly descriptive was the name given to that mountain by the Amorites - Shenir, the "breastplate," or "shield" (Deut. 3:9).For an hour or more I sat wrapped in the contemplation of the wide and wondrous panorama. At least a thousand square miles of Og’s ancient kingdom were spread out before me. There was the country whose "giant" (Rephaim, Gen. 14.) inhabitants the eastern kings smote before they descended into the plain of Sodom. There were those "three score great cities" of Argob, whose "walls, and gates, and brazen bars" were noted with surprise by Moses and the Israelites, and whose Cyclopean architecture and massive stone gates even now fill the western traveller with amazement, and give his simplest descriptions much of the charm and Strangeness of romance. So clear was the air that the outline of the most distant objects was sharp and distinct. Hermon itself, though forty miles away, did not seem more than eight or ten, when the sun embossed its furrowed sides with light and shade.

I was at length roused from a pleasing reverie by the deep voice of Sheikh Assad giving a cordial and truly patriarchal salutation.

"What a glorious view you have from this commanding spot!" I said, when the compliments were over.

"Yes, we can see the Bedawîn at a great distance, and have time to prepare for them," was his characteristic reply.

"What! do the desert tribes, then, trouble you here; and do they even venture to plunder the Druses?"

"Not a spot of border land from Wady Műsa to Aleppo is safe from their raids, and Druses, Moslems, and Christians are alike to them. In fact, their hand is against all. When the Anezeh come up in spring, their flocks cover that plain like locusts, and were it not for our rifles they would not leave us a hoof nor a blade of corn. To-day their horsemen pillage a village here; to-morrow, another in the Ghutah of Sham (Damascus); and the day following they strip the Baghdad caravan. Oh, my lord! these sons of Ishmael are fleet as gazelles, and fierce as leopards. Would Allah only rid us of them and the Turks, Syria might prosper."

The Sheikh described the Arabs to the life, just as they were described by the spirit of prophecy nearly four thousand years ago. "He (Ishmael) shall be a wild man; his hand against every man, and every man’s hand against him; and he shall dwell in the presence of all his brethren" (Gen. 16:12). These "children of the east" come up now as they did in Gideon’s days, when "they destroyed the increase of the earth, and left no sustenance for Israel; neither sheep, nor ox, nor ass. For they came up with their cattle and their tents, and they came as grasshoppers for multitude; both they and their camels were without number; and they entered into the land to destroy it" (Judges 6:4, 5). During the course of another tour through western part of Bashan, I rode in one day for more than twenty miles in a straight course through the flocks of an Arab tribe.

On remarking to the Sheikh the great number of old cities in view, he pointed out to me the largest and most remarkable of them; and among these I heard with no little interest, the name of Edrei, the ancient capital of Bashan, and the residence of Og, the last of its giant-kings. Others there were too, such as Shuka, and Bathanyeh, and Musmieh, whose names, as we shall see, are not unknown in history.

From a general survey of the country I turned to an examination of the town. Hit is in form rectangular, and about a mile and a half in circumference. I traced most of the old streets, though now in a great measure filled up with fallen houses and heaps of rubbish, the accumulations of long centuries. The streets were narrow and irregular, and thus widely different from those laid out in many other cities in this land by Roman architects. A large portion of the town is ruinous; but some of the very oldest houses are still perfect. They are simple and massive in style, containing only one story, and generally two or three large rooms opening on an enclosed court. The walls are built of large stones roughly hewn, though closely jointed, and laid without cement. The roofs are formed of long slabs placed horizontally from wall to wall;" thus forming the flat "house tops," where the people are now accustomed to sit and pray, just as they were in New Testament times. Indeed, the "house-top" is the favourite prayer-place of Mohammedans in Syria (see Acts 10:9; Matt. 24:17; Isa. 15:3; Zeph. 1:5). The doors are stone, and I saw many tastefully ornamented with panels and garlands of fruit and flowers sculptured in relief. There is not a single new, or even modern, house in Hit. The Druses have taken possession and settled down without any attempt at alteration or addition. Those now occupied are evidently of the most remote antiquity, and not more than half of the habitable dwellings are inhabited. I saw the remains of several Greek or Roman temples, and a considerable number of Greek inscriptions on the old houses, and on loose stones. The inscriptions have no historic value, being chiefly votive and memorial tablets: two of them have dates corresponding to A.D. 120, and A.D. 208. Nothing is known of the history of Hit; we cannot even tell its ancient name; but its position, the character of its houses and of its old massive ramparts, seem to warrant the conclusion that it was one of those "three score great cities" which Jair captured in Argob (Deut. 3:4, 14).

The news of our arrival had already reached Sheikh Fares, the elder brother of our host, and one of the most powerful chiefs in Haurân. While we sat at breakfast a messenger arrived with an urgent request that we should visit him and spend the night at his house in Shuhba. We gladly consented; and as that town is only four miles south of Hit, we resolved to employ the day in exploring the northern section of the mountain range. Our horses were soon at the door. Sheikh Assad supplied an active, intelligent, and well-mounted guide, and his own nephew, a noble-looking youth of one-and-twenty, volunteered his services as escort. Mounting at once, amid the respectful salâms of a crowd of white-turbaned Druses, we rode off northward in the track of an old Roman road. Finely-cultivated fields skirted our path for some distance, already green with young wheat, and giving promise of luxuriance such as is seldom seen in Palestine. The day was bright and cool, the ground firm and smooth, our horses fresh, and our own spirits high. Our new companions, too, were eager to display the mettle of their steeds, and their unrivalled skill in horsemanship. So, loosening the rein, we dashed across the gentle slopes, and only drew bridle on reaching Bathanyeh, about four miles from Hit. Along our route for a mile and more, we observed the openings of a subterranean aqueduct, intended in former days to supply the city with water. Such aqueducts are common on the eastern border of Syria and Palestine, especially in Haurân and the plain of Damascus. They appear to have been constructed as follows: - A shaft was sunk to the depth of from ten to twenty feet, at a spot where it was supposed water might he found; then a tunnel was excavated on the level of the bottom of the shaft, and in the direction of the town to be supplied. At the distance of about a hundred yards another shaft was sunk, connecting the tunnel with the surface; and so the work was carried on until it was brought close to the city, where a great reservoir was made. Some of these aqueducts are nearly twenty miles in length; and even though no living spring should exist along their whole course, they soon collect in the rainy season sufficient surface water to supply the largest reservoirs. Springs are rare in Bashan. It is a thirsty land; but cisterns of enormous dimensions-some open, others covered - are seen in every city and village. It was doubtless by some such "conduit" as this that Hezekiah took water into Jerusalem from the upper spring of Gihon (2 Kings 20:20).

ANCIENT CITIES.

Scrambling through, or rather over, a ruinous gateway, we entered the city of Bathanyeh. A wide street lay before us, the pavement perfect, the houses on each side standing, streets and lanes branching off to the right and left. There was something inexpressibly mournful in riding along that silent street, and looking in through half-open doors to one after another of those desolate houses, with the rank grass and weeds in their courts, and the brambles growing in festoons over the doorways, and branches of trees shooting through the gaping rents in the old walls. The ring of our horses' feet on the pavement awakened the echoes of the city, and startled many a strange tenant. Owls flapped their wings round the gray towers; daws shrieked as they flew away from the house-tops; foxes ran out and in among shattered dwellings, and two jackals rushed from an open door, and scampered off along the street before us. The graphic language of Isaiah, uttered regarding another city, but vividly descriptive of desolation in any place, came up at once to my mind and to my lips: - "Wild beasts of the desert shall lie there; and their houses shall be full of doleful creatures; and owls shall dwell there, and satyrs shall dance there" (Isa. 13:21).Bathanyeh stands on the northern declivity of the mountains of Bashan, and commands a view of the boundless plain towards the lakes of Damascus. About a mile and a half to the north-west I saw two large villages close together. Two miles further, on the top of a high tell, were the ruins of a town, which, my guides said, are both extensive and beautiful. Three other towns were visible in the plain, and two on the slopes eastward. How we wished to visit these I but time would not permit. From this, as from every other point where I reached the limits of my prescribed tour, I turned aside with regret; because away beyond, the eye rested on enticing ruins, and unexplored towns and villages.

Bathanyeh is not quite so large as Hit, but the buildings are of a superior character and in much better preservation. One of the houses in which I rested for a time might almost be termed a palace. A spacious gateway, with massive folding-doors of stone, opened from the street into a large court. On the left was a square tower some forty feet in height. Round the court, and opening into it, were the apartments, all in perfect preservation; and yet the place does not seem to have been inhabited for centuries. Greek inscriptions on the principal buildings prove that they existed at the commencement of our era; and in the whole town I did not see a solitary trace of Mohammedan occupation, so that it has probably been deserted for at least a thousand years. The name at once suggests its identity with Batanis, one of the thirty-four ecclesiastical cities of Arabia, whose bishops were in the fifth century suffragans of the primate of Bostra. Batanis was the capital or the Greek province of Batanaea, a part of the tetrarchy of Philip, mentioned by Josephus, but included by Luke (3:1) In the "region of Trachonitis." The region round it is still called "the Land of Batanea;" and the name is interesting as a modern representative of the Scriptural Bashan.

Turning away from this interesting place, we rode along the mountain side eastward to Shuka, four miles distant. This is also a very old town, and must at one time have contained at least 20,000 inhabitants, though now it has scarcely twenty families. Ptolemy, the Greek geographer, calls it Saccaea. It was evidently rebuilt by the Romans, as only a very few of its antique massive houses remain, and the shattered ruins of temples are seen on every side. One of these temples was long used as a church, and the ruins of another church also exist, which, an inscription tells us, was dedicated by Bishop Tiberinos to St. George in A.D. 369. Around Shuka are some remarkable tombs, square towers, about twenty feet on each side, and from thirty to forty high, divided into stories. Tablets over the doors record the names of the dead who once lay there, and the dates of their death. They are of the first and second centuries of our era. They have been all rifled, so that we cannot tell how the bodies were deposited, though probably the arrangements were similar to those in the tombs of Palmyra. From the ruins of Shuka three other towns were in sight among the hills on the east.

Remounting, we rode for ten miles through a rich agricultural district to Shuhba. We passed only one village, but we saw several towns on the wooded sides of the mountain to the left, and numerous others down on the plain to the right. Crossing a rugged ravine, and ascending a steep bank, we reached the walls of Shuhba. They are completely ruined, so much so, that the only way into the city is over them, beside a beautiful Roman gateway, now blocked up with rubbish. Having entered, we proceeded along a well-paved street - the most perfect specimen of Roman pavement I had yet seen - to the residence of the chief. In the large area in front of his mansion we found a crowd of eager people, and the first to hold out the hand of welcome was our kind host of the previous night, Sheikh Assad. He introduced us to his brother Fares, and we were then ushered into an apartment where we found comfort, smiling faces, and a hearty welcome.

Shuhba is almost entirely a Roman city - the ramparts are Roman, the streets have the old Roman pavement, Roman temples appear in every quarter, a Roman theatre remains nearly perfect, a Roman aqueduct brought water from the distant mountains, inscriptions of the Roman age, though in Greek, are found on every public building. A few of the ancient massive houses, with their stone doors and stone roofs, yet exist, but they are in a great measure concealed or built over with the later and more graceful structures of Greek and Roman origin. Though this city was nearly three miles in circuit, and abounded in splendid buildings, its ancient name is lost, and its ancient history unknown. Its modern name is derived from a princely Mohammedan family which settled here in the seventh century. The Emir Beshir Shehab, the last of the native rulers of Lebanon, was a member of the family, and so also was the Emir Saad-ed-Din, who was murdered in the late massacre at Hasbeiya on the side of Hermon.

Beside Shuhba is a little cup-shaped hill which caught my eye the moment I entered the city. On ascending I found it to be the crater of an extinct volcano, deeply covered with ashes, cinders, and scoriae - one of the centres, doubtless, of that terrific convulsion which in some remote age heaved up the mountains of Bashan, and spread out the molten lava which cooled into the rock fields of Argob. From the summit I had a near and distinct view of the south-eastern section of Argob. Its features are even wilder and drearier than those of the northern. The rocks are higher, the glens deeper and more tortuous. It looks, in fact, like the ruins of a country, and yet towns and villages axe thickly studded over that wilderness of rocks. The mountains which rise behind Shuhba on the east are; terraced half-way up, and their tops are clothed with oak forests. The vine and the fig flourished here luxuriantly in the days of Bashan’s glory, winter streams then irrigated and enriched the slopes, and filled the great cisterns in every city; but the Lord said in his wrath, "I will make waste mountains and hills, and dry up all their herbs; and I will make the rivers islands, and I will dry up the pools" (Isa. 42:15), and now I saw that the words of the Lord were literally and fearfully true.

Sheikh Fares and his brother made all requisite arrangements for our future tour through Bashan. They told us that so long as we travelled in the Druse country we should be perfectly safe; no hand, no tongue, would be lifted against us; a welcome would meet us in every village, and a cordial wish for our welfare follow us on every path. We knew this, for we knew that policy as well as the sacred laws of Oriental hospitality, would constrain the Druses to aid and protect us to the utmost of their power. They warned us, however, that some parts of our proposed journey would be attended with considerable risk. They told us plainly that the Mohammedans could not be trusted, and that if we attempted to penetrate the Lejah (Argob), all the power of the Druses might not be sufficient to save us from the fury of excited fanatics. We attributed these warnings to the best motives, but we thought them exaggerated. To our cost we afterwards found that they were only too much needed. Sheikh Fares gave us one of the most intelligent and active of his men as guide and companion, he also supplied horses for our servants and baggage, and a Druse escort. Thus equipped, we bade farewell to our kind and generous host, and set out on our journey southward. For more than an hour we followed the course of a Roman road along the western declivity of the mountain range, passing several old villages on the right and left. At one of these villages, picturesquely situated in a secluded glen, we saw a long procession of Druse women near a clump of newly-made graves. They had a strange unearthly look. The silver horns, which they wear upright on their heads, were nearly two feet long, over these were thrown white veils, enveloping the whole person, and reaching to the ground, thus giving them a stature apparently far exceeding that of mortals. As they marched with stately steps round the tombs, they sung a wild chant that now echoed through the whole glen, and now sunk into the mournful cadence of a death-wail. I asked the meaning of this singular and striking scene, and was told that eleven of the bravest men in the village had fallen in the late war, these were their graves, and now the principal women of Shuhba had come to comfort and mourn with the wives of the slain; just as, in the time of our Lord, many of the Jews came from Jerusalem "to comfort Martha and Mary concerning their brother Lazarus" (John 11:18-31).

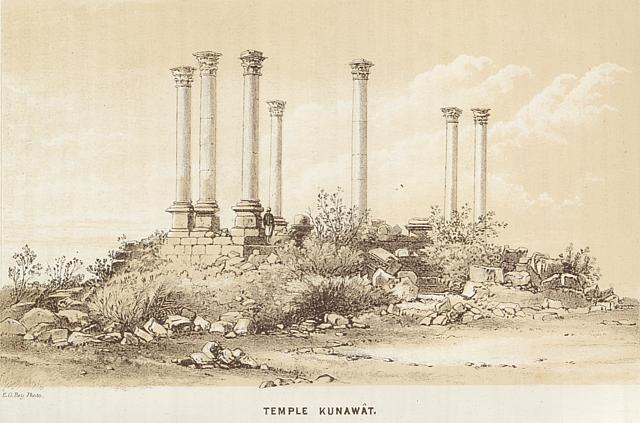

Descending a rugged bank into a rich plain, a quarter of an hour’s gallop brought us to Suleim, a small but ancient town, containing the remains of a beautiful temple, and some other imposing buildings. A few Druses, who find ample accommodation in the old houses, gathered round us, and pressed us to accept of their hospitality. We were compelled to decline, and after examining a group of remarkable subterranean cisterns, we mounted again and turned eastward up a picturesque valley to Kunawât. The scenery became richer and grander as we ascended. The highest peaks of the mountains of Bashan were before us, wooded to their summits. On each side were terraced slopes, broken here and there by a dark cliff or rugged brake, and sprinkled with oaks; in the bottom of the dell below, a tiny stream, the first we bad seen in Bashan, leaped joyously from rock to rock, while luxuriant evergreens embraced each other over its murmuring waters. From the top of every rising ground we looked out over jungle and grove to gray ruins, which here and there reared themselves proudly above dense masses of foliage. Diving into the dell by a path that would try the nerves of a mountain goat, we crossed the streamlet and wound up a rocky bank, among giant oaks and thick underwood, to an old building which crowns a cliff impending over the glen. As we rode up we could obtain a glimpse of its gray walls here and there through dark openings, but on reaching the broad terrace in front of it, and especially on entering its spacious court, we were struck as much with its extent as with the beauty of its architecture. The doorway is encircled by a broad border of the fruit and foliage of the vine, entwined with roses and lilies, sculptured in bold relief, and with equal accuracy of design and delicacy of execution. The court was surrounded by cloisters supported by Ionic columns, but nearly all gone now. On the north side is a projection containing a building at one period used as a church, but probably originally intended for a temple. The ruins of another building, the shrine or sanctuary of the whole, are strewn over the centre of the quadrangle. The graceful pillars, and sculptured pediment, and cornice with its garlands of flowers, lie in shapeless heaps beneath the shade of oak trees, and almost concealed by thorns and thistles. Yes, the curse is visible there, not so painfully visible perhaps as in Western Palestine, where only a few stones or heaps of rubbish mark the site of great cities, yet still visible in crumbling wall and prostrate column, and in those very brambles that weave a beauteous mantle round the fallen monuments of man’s genius and power. "Thorns shall come up in her palaces, nettles and brambles in the fortresses thereof." - They are here.

KENATH.

A few minutes' ride brought us to the brow of a hill commanding a view of Kunawât. On the left was a deep dark ravine, and on the sloping ground along its western bank lie the ruins of the ancient city. The wall, still in many places almost perfect, follows the top of the cliffs for nearly a mile, and then sweeps round in a zigzag course, enclosing a space about half a mile wide. The general aspect of the city is very striking-temples, palaces, churches, theatres, and massive buildings whose original use we cannot tell, are grouped together in picturesque confusion; while beyond the walls, in the glen, on the summits and sides of wooded peaks, away in the midst of oak forests, are clusters of columns and massive towers, and lofty tombs. The leading streets are wide and regular, and the roads radiating from the city gates are unusually numerous and spacious.While the Israelites were engaged in the conquest of the country east of the Jordan, Moses tells us that "Nobah went and took Kenath, and the villages thereof, and called it Nobah, after his own name" (Num. 32:42). Kenath was now before us. The name was changed into Canatha by the Greeks; and the Arabs have made it Kunawât. During the Roman rule it was one of the principal cities east of the Jordan; and at a very early period it had a large Christian population, and became the seat of a bishopric. It appears to have been almost wholly rebuilt about the commencement of our era, and is mentioned by most of those Greek and Roman writers who treat of the geography or history of Syria. At the Saracenic conquest Kenath fell into the hands of the Mohammedans, and then its doom was sealed. There are no traces of any lengthened Mohammedan occupation, for there is not a single mosque in the whole town. The heathen temples were all converted into churches, and two or three new churches were built; but none of these buildings were ever used as mosques, as such buildings were in most of the other great cities of Syria.

We spent the afternoon and some hours of the next day in exploring Kenath. Many of the ruins are beautiful and interesting. The highest part of the site was the aristocratic quarter. Here is a noble palace, no less than three temples, and a hippodrome once profusely adorned with statues. In no other city of Palestine did I see so many statues as there are here. Unfortunately they are all mutilated; but fragments of them - heads, legs, arms, torsos, with equestrian figures, lions, leopards, and dogs-meet one on every side. A colossal head of Ashteroth, sadly broken, lies before a little temple, of which probably it was once the chief idol. The crescent moon which gave the goddess the name Carnaim ("two-horned"), is on her brow. I was much interested in this fragment, because it is a visible illustration of an incidental allusion to this ancient goddess in the very earliest historic reference to Bashan. We read in Gen. 14:5, that the kings of the East, on their way to Sodom, "smote the Rephaims in Ashteroth-Karnaim." May not this be the very city? We found on examination that the whole area in front of the palace has long ranges of lofty arched cisterns beneath it, something like the temple-court at Jerusalem. These seemed large enough to supply the wants of the city during the summer. They were filled by means of an aqueduct excavated in the bank of the ravine, and connected probably with some spring in the mountains. The tombs of Kenath are similar to those of Palmyra-high square towers divided into stories, each story containing a single chamber, with recesses along the sides for bodies. About a quarter of a mile west of the city is a beautiful peripteral temple of the Corinthian order, built on an artificial platform. Many of the columns have fallen, and the walls are much shattered; but enough remains to make this one of the most picturesque ruins in the whole country.

Early in the morning we set out to examine the ruins in the glen, and to scale a high cliff on its opposite bank, where we had noticed a singular round tower and some heavy fragments of walls. The glen appears to have been anciently laid out as a park or pleasure ground. We found terraced walks, and little fountains now dry, and pedestals for statues, a miniature temple, and a rustic opera, whose benches are hewn in the side of the cliff; a Greek inscription in large characters round the front of the stage, tells us that it was erected by a certain Marcus Lusias, at his own expense, and given to his fellow-citizens. From the opera a winding stair-case, hewn in the rock, leads up to the round tower on the summit of the cliff. We ascended, and were well repaid alike for our early start and toil. The tower itself has little interest; it is thirty yards in circuit, and now about twenty feet high; the masonry is colossal and of great antiquity. Beside it are the remains of a castle or palace, built of bevelled stones of enormous size. The doors are all of stone, and some of them are ornamented with panels and fretted mouldings, and wreaths of fruit and flowers sculptured in high relief. In one door I observed a place for a massive lock or bar; perhaps one of those "brazen bars" to which allusion is made by the sacred writers (1 Kings 4:13). But it was the glorious view which these ruins command that mainly charmed us. As I sat down on a great stone on the brow of the ravine, my eye wandered over one of the most beautiful panoramas I ever beheld. From many a spot amid the lofty peaks of Lebanon I had looked on wilder and grander scenery. Standing on the towering summit of the castle at Palmyra, ruins more extensive and buildings far more magnificent lay at my feet. From the Cyclopean walls of the Temple of the Sun at Baalbec I saw prouder monuments of man’s genius, and more exquisite memorials of his taste and skill. But never before had I looked on a scene which nature, and art, and destruction had so combined to adorn. It was not the wild grandeur of Lebanon, with beetling cliff and snow-capped peak; it was not the flat and featureless Baalbec, with its Cyclopean walls and unrivalled columns; it was not the blasted desolation of Palmyra, where white ruins are thickly strewn over a white plain. Here were hill and vale, wooded slopes and wild secluded glens, frowning cliffs and battlemented heights, moss-grown ruins and groups of tapering columns springing up from the dense foliage of the oaks of Bashan. Hitherto I had been struck with the nakedness of Syrian ruins. They are half-buried in dust, or they are strewn over mounds of rubbish, or they lie prostrate on the bare gravelly soil; and, though the shafts are graceful, the capitals chaste, the fretwork of frieze and cornice rich, yet, as pictures, they contrast poorly with the ivy-mantled abbeys of England, and the nature-clothed castles of the Rhine. Amid the hills of Bashan, however, the scene is changed. The fresh foliage hides defects, and enhances the beauty of stately portico and massive wall, while luxuriant creepers twine round the pillars, and wreathe the volutes of the capitals with garlands.

SHEPHERDS LEADING THEIR FLOCKS.

As we sat and looked, almost spell-bound, the silent hill-sides around us were in a moment filled with life and sound. The shepherds led their flocks forth from the gates of the city. They were in full view, and we watched them and listened to them with no little interest. Thousands of sheep and goats were there, grouped in dense, confused masses. The shepherds stood together until all came out. Then they separated, each shepherd taking a different path, and uttering as he advanced a shrill peculiar call. The sheep heard them. At first the masses swayed and moved, as if shaken by some internal convulsion; then points struck out in the direction taken by the shepherds; these became longer and longer until the confused masses were resolved into long, living streams, flowing after their leaders. Such a sight was not new to me, still it had lost none of its interest. It was perhaps one of the most vivid illustrations which human eyes could witness of that beautiful discourse of our Lord recorded by John - "And the sheep hear the shepherd’s voice: and he calleth his own sheep by name, and leadeth them out, and when he putteth forth his own sheep, he goeth before them and the sheep follow him; for they know his voice. And a stranger will they not follow: for they know not the voice of strangers" (10:3-5).The shepherds themselves had none of that peaceful and placid aspect which is generally associated with pastoral life and habits: They looked more like warriors marching to the battle-field-a long gun slung from the shoulder, a dagger and heavy pistols in the belt, a light battle-axe or iron-headed club in the hand. Such were their equipments; and their fierce flashing eyes and scowling countenances showed but too plainly that they were prepared to use their weapons at any moment. They were all Arabs - not the true sons of the desert, but a mongrel race living in the mountains, and acting as shepherds to the Druses while feeding their own flocks. Their costume is different from that of the Druses, and almost the same as that of the desert Arabs - a coarse shirt of blue calico bound round the waist by a leathern girdle, a loose robe of goats' hair, and a handkerchief thrown over the head and fastened by a fillet of camels' hair, - such is their whole costume, and it is filthy besides, and generally in rags.