YOU DON'T HAVE TO COME BACK!

By J. R. Lee,

AOC, USCG, Retired

And Ted A.

Morris, Lt. Col., USAF, Retired

In a sister aircraft, number 59012, the left wing float and five feet of the left wing tip

were torn away during a night JATO lift off from rough open ocean waters.

Pilots MacDowell and Douglas flew the damaged aircraft back to home base.

They made a successful night water landing ending the hazardous rescue mission of April 7-8, 1948.

It has been more than three quarters of a century since

Congress and President Woodrow Wilson merged the United

States Revenue Cutter Service (formed in 1790 by

Alexander Hamilton) and the United States Life Saving

Service (which dates back to 1847) to form the United

States Coast Guard.

The official Coast Guard motto "SEMPER PARATUS", "Always Ready", has been Guiding Light for those worthy members of this service, whose duties have been expanded and added to many times over. The greatest of these duties has always been to preserve the lives of those "who go down to the sea in ships".

More than half a century ago the words spoken by a Coast Guard Surfman at the scene of a surfboat launching have become the unofficial battle cry of Coast Guardsmen to this day. In the teeth of an Atlantic storm, a large merchant vessel foundered. A Coast Guard surfboat was being launched into the surf in an effort to reach the ship and rescue the crew. A reporter at the scene asked the Surfman in charge why they were attempting this seemingly impossible task. The Surfman replied, "They say you must go out and try, they don't say anything about coming back!"

In the tradition of these words, a Coast Guard rescue mission began on 7 April 1948. Late that afternoon, Seventh Coast Guard District's Rescue Coordination Center, Miami, Florida, received a radio message requesting assistance. An explosion and fire on board the British merchant vessel WILCOX in the Gulf of Mexico 300 miles south of Miami, left crew member Wong Cheng with severe burns covering most of his body. Cheng was in desperate need of medical care, much more than was available aboard the WILCOX. Coast Guard Air Station, Miami, at Dinner Key was tasked to provide a medical evacuation "mercy mission".

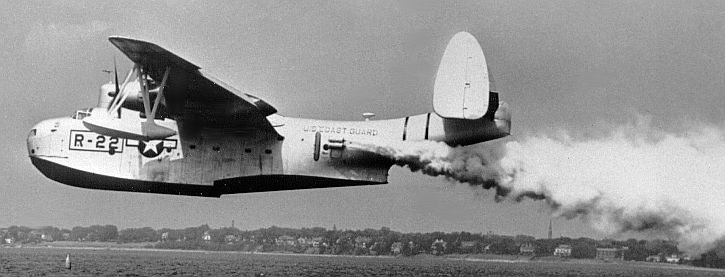

The alert rescue PSM-5 seaplane 59012, under the

command of Lieutenant Charles MacDowell, with Chief

Aviation Pilot R. 0. Douglas as co-pilot, and Lieutenant

Rufus Drury as navigator, was made ready and launched

within minutes of receiving the message to go!

Launching a 30-ton PBM-5 seaplane was a complicated

task requiring much skill and coordination between the

aircraft crew and the beaching crew on shore. The

rescue aircraft crew members scrambled on board, donned

Mae West life jackets and parachutes, and started the

auxiliary power unit to provide electrical power to

start the two large R-2800 Pratt and Whitney double wasp

18 cylinder engines. The radio system was checked

and communication with Air Station Operations

established. The pilot then signaled the

beachmaster Bill Pinkston to launch the PBM-5.

With aircraft engines idling, powerful winches on each side of the ramp pulled on ropes that formed a bridle used to pull the aircraft down the seaplane ramp into the water. A beaching crew member on a caterpillar tractor provided a brake to prevent the aircraft from going down the ramp too fast or sliding side ways.

When the PBM-5 was afloat in the water, the winches

and bridle pulled the aircraft away from shore.

The pilot then gave the signal to the aircraft crew

members to disengage the massive side beaching gear

wheels from the aircraft. A beaching crew member

disengaged the after beaching gear wheels and the

beaching crew hauled these devices ashore. Aircrew

member Walter Pierce released the cable secured to the

tractor, the winches and bridle gear pulled the PBM-5

clear of the shore. Aircrew member Jack McElyea

cast loose the nose bridle from the aircraft.

The aircraft was now free of the shore and Lt.

MacDowell taxied to the seadrome landing and take off

area. The Air Station crashboat cleared all

vessels from the area and stood by as the "mercy

mission" aircraft began its take off run. When the

PBM-5 was airborne, navigator Lt. Drury laid out a

course to the position provided by the WILCOX.

After a Flight of several hours, daylight fading, PBM-5 59012 arrived at the position only to discover an empty sea. Through radio communication, Captain George Bell of the WILCOX was requested to recompute and provide the correct position of his ship. Precious hours of daylight had been used before arriving at the correct WILCOX location.

Lt. MacDowell and CAP Douglas made several low passes over the ship to check the condition of the sea. The surface was becoming rough with swells of three to four feet. A 15-knot wind, strong enough to cause white caps, made a hazardous condition to land the large aircraft. Dropping a smoke float to mark the landing area and monitor wind conditions, Lt. MacDowell requested the WILCOX to launch a small boat to stand by in case of an accident during landing or take off.

The open sea landing was rough, throwing aircrew

members about but causing no injuries. The PBM-5

was thoroughly checked over by the aircrew to insure no

damage had been sustained and that no leaking was taking

place.

The WILCOX's small boat, Wong Cheng aboard, immediately

came alongside the open waist hatch of the PBM-5.

This is a very hazardous operation as it is very easy to

damage the thin skinned aircraft. Coxswain Hurley

Boyd did an excellent job in maneuvering and the

severely burned Cheng was transferred into the pitching

aircraft without incident.

On board the rescue aircraft, U.S. Public Health Service Doctor LCDR J. P. Ciccone quickly checked the condition of his patient and insured Cheng was properly secured for take off and the flight back to medical help.

Daylight was now all but gone as Lt. MacDowell and CAP Douglas maneuvered the aircraft for take off from the increasingly rough seas. Aircrew members attached four Jet Assisted Take Off (JATO) bottles to the external racks. When ignited each JATO bottle provided 1,000 pounds of thrust for 15 seconds to assist in getting the PBM-5 airborne.

The pilots checked everything ready and advanced the engines to take off power as the aircraft bounced and pushed through the sea reaching take off speed. Lt. MacDowell pushed the button to fire the JATO. As the bottles fired, the aircraft bounced across the waves and lurched to the left. A loud noise was heard over the roar of the JATO and the engines.

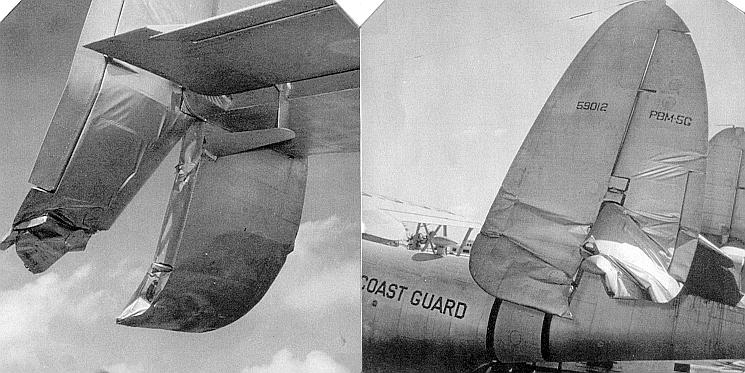

PBM-5 59012 was airborne! The pilots, however,

were having many problems trying to get the aircraft to

climb in a straight and normal attitude. The

control surfaces were extremely difficult to move.

Crewmember Pierce climbed to the aft position up between

the twin rudders. Using a flashlight he could see

that the left rudder appeared damaged and jammed out of

alignment. Checking the left side of the wing, he

discovered the left wing tip float was missing along

with about five feet of the left wing tip. The

left aileron had also been damaged!

Note the damaged left wing tip and aileron, and missing left wing float.

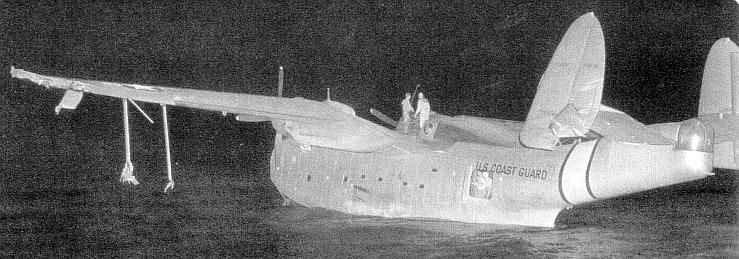

The hazardous night landing was made in Biscayne Bay, and the aircrew taxied the damaged aircraft

onto Sport Island just before the rising tide covered it. The injured seaman, Wong Cheng,

was removed by crash boat and transferred to medical treatment ashore.

Pilots MacDowell and Douglas maintained control of the aircraft with sheer muscle power while navigator Drury set a course for Miami. Rescue Coordination Center in Miami was notified of the emergency situation, that the crew would make every effort to bring the "mercy mission" back home.

A PBM-5 From Coast Guard Air Station, St. Petersburg, and a PBY-5A From Dinner Key were launched to provide rescue coverage to 59012 as the aircrew struggled to maintain control of the aircraft.

It was now a very dark night, a hazardous condition For a water landing even For an aircraft in good condition. The PBM-5 was a seaplane, it did not have wheels. Unlike the amphibious model, the PBM-5A, it could not land on land. MacDowell, Douglas and the aircrew members discussed what their options could be. Try to land the damaged aircraft on land at Opalocka Naval Air Station after bailing out the crew, with the exception of the pilots and severely burned patient. Or, try a water landing back at Dinner Key without a wing tip float and a very difficult aircraft to control. With the confidence of the aircrew in their pilots, the decision to attempt to complete the mission at Dinner Key was made.

Commander R. F. Schuck, commander of Air Station, Miami, alerted all available resources to aid in the landing. Coast Guard crash boats from the Air Station, vessels from the Coast Guard base on MacArthur Causeway, the Miami harbor patrol and a fireboat, yachts from the Coast Guard auxiliary, all reported to the seadrome landing area. The area was cleared of all vessels and debris, floodlights were positioned to light the area.

Pilots MacDowell and Douglas, their strength having been drained by the great effort to manually manhandle the controls, were relieved at times by navigator Drury and flight engineer Leo Thompson.

As 59012 approached to make the landing, aircrew members checked that the patient and Doctor Ciccone were securely in place, that all water tight compartments were secured and everyone in-place for the landing.

Pilots MacDowell and Douglas tested all controls and prepared for a hazardous night landing. As they brought their 30-ton seaplane to an extremely smooth landing in the sheltered waters of Biscayne Bay, the top hatch was opened and crew members Pierce, McElyea and Q. C. Frazier scrambled out onto the top of the aircraft and onto the right wing. The right side was made heavy so that the left wing would not dip into the water causing the aircraft to water loop as it slowed down. An Air Station crash boat maneuvered into position under the left wing float position to prevent the aircraft from capsizing.

PBM-5 59012 was then taxied onto a small sand spit named Sporl Island and came to rest. Dr. J.P. Ciccone and patient Wong Cheng were lowered into a crash boat and soon on the way to medical care. The "mercy mission" of PBM-5 59012 and its courageous air crew was over.

"You have to go out and try, you don't have to come back". Some rescue attempts by Coast Guard personnel have not always had the success of PBM-5 59012, but they have always tried.

The "mercy mission" air crew, Coast Guardsmen LTs

Charles MacDowell and Rufus Drury, Chief R. 0. Douglas,

and crewmen Leo Thompson, Walter Pierce, Q. C. Frazier,

Jack McElyea, Wade Midciff, and Public Health Service

Doctor J. P. Ciccone were honored at a General Muster by

Commandant Admiral Merlin O'Neill For a hazardous job

well done.

Showing the damage to the left tail fin and rudder.

Showing the damage to the left wingtip and aileron, and the struts to the missing left wingfloat.