| Types of Government

The United States has established a representative democracy

that serves as a model for government and inspires people around the world.

Students in China in 1989 marched for “government of the people, by the

people, and for the people.” Yet other forms of government outnumber true

democracies. Over the centuries, people have organized their governments

in many different ways. In Saudi Arabia, for example, the ruling

royal family controls the government and its resources. Family members

choose the king from among themselves. Thousands of miles away, in

Burkina Faso in Africa, a small group of wealthy landowners and military

officers governs that country. In Sweden the people elect the Riksdag,

the national legislature, which in turn selects the prime minister to carry

out the laws.

Major Types of Government

Governments can be classified in many ways. The

most time-honored system comes from the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher

Aristotle. It is based on a key question: Who governs the state?

Under this system of classification, all governments belong to one of three

major groups: (1) autocracy—rule by one person; (2) oligarchy—rule by a

few persons; or (3) democracy—rule by many persons.

Autocracy

| Any system of government in which the power and authority

to rule are in the hands of a single individual is an autocracy.

This is the oldest and one of the most common forms of government.

Historically, most autocrats have maintained their positions of authority

by inheritance or the ruthless use of military or police power. Several

forms of autocracy exist. One is an absolute or totalitarian dictatorship.

In a totalitarian dictatorship, the ideas of a single leader or

group of leaders are glorified. The government seeks to control all

aspects of social and economic life. Examples of totalitarian dictatorship

include Adolf Hitler’s government in Nazi Germany (from 1933 to 1945),

Benito Mussolini’s rule in Italy (from 1922 to 1943), and Joseph Stalin’s

regime in the Soviet Union (from 1924 to 1953). In such dictatorships,

government is not responsible to the people, and the people lack the power

to limit their rulers. |

|

Napoleon Bonaparte, especially

as emperor, became an absolute dictator in his rule over what is known

as the French Empire. |

Monarchy is another form of autocratic government.

In a monarchy a king, queen, or emperor exercises the supreme powers of

government. Monarchs usually inherit their positions. Absolute

monarchs have complete and unlimited power to rule their people.

The king of Saudi Arabia, for example, is such an absolute monarch.

Absolute

monarchs are rare today, but from the 1400s to the 1700s, kings or

queens with absolute powers ruled most of Western Europe.

Today some countries, such as Great Britain, Sweden, Japan,

and the Netherlands, have constitutional monarchs. These monarchs

share governmental powers with elected legislatures or serve mainly as

the ceremonial leaders of their governments.

Oligarchy

An oligarchy is any system of government in which

a small group holds power. The group derives its power from wealth,

military power, social position, or a combination of these elements.

Sometimes religion is the source of power. Today the governments

of Communist countries, such as China, are mostly oligarchies. In

such countries, leaders in the Communist Party and the armed forces control

the government.

Both dictatorships and oligarchies sometimes claim they

rule for the people. Such governments may try to give the appearance

of control by the people. For example, they might hold elections,

but offer only one candidate, or control the election results in other

ways. Such governments may also have some type of legislature or

national assembly elected by or representing the people.

These legislatures, however, approve only policies and

decisions already made by the leaders. As in a dictatorship, oligarchies

usually suppress all political opposition—sometimes ruthlessly.

Democracy

A democracy is any system of government in which

rule is by the people. The term democracy comes from the Greek demos

(meaning “the people”) and kratia (meaning “rule”). The ancient Greeks

used the word democracy to mean government by the many in contrast to government

by the few. Pericles, a great leader of ancient Athens, declared,

“Our constitution is named a democracy because it is in the hands not of

the few, but of the many.”

The key idea of democracy is that the people hold sovereign

power. Abraham Lincoln captured this spirit best when he described

democracy as “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

Democracy may take one of two forms. In a direct

democracy, the people govern themselves by voting on issues individually

as citizens. Direct democracy exists only in very small societies

where citizens can actually meet regularly to discuss and decide key issues

and problems. Direct democracy is still found in some New England

town meetings and in some of the smaller states, called cantons, of Switzerland.

No country today, however, has a government based on direct democracy.

In an indirect or representative democracy, the people

elect representatives and give them the responsibility and power to make

laws and conduct government. An assembly of the people’s representatives

may be called a council, a legislature, a congress, or a parliament.

Representative democracy is practiced in cities, states, provinces, and

countries where the population is too large to meet regularly in one place.

It is the most efficient way to ensure that the rights of individual citizens,

who are part of a large group, are represented.

In a republic, voters are the source of the government’s

authority. Elected representatives who are responsible to the people

exercise that power. As Benjamin Franklin was leaving the Constitutional

Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, a woman approached him and asked, “What

kind of government have you given us, Dr. Franklin? A republic or

a monarchy?” Franklin answered, “A republic, Madam, if you can keep it.”

Franklin’s response indicated that the Founders preferred

a republic over a monarchy but that a republic requires citizen participation.

For most Americans today, the terms representative democracy,

republic,

and constitutional republic mean the same thing: a system

of limited government where the people are the ultimate source of governmental

authority. It should be understood, however, that throughout the

world not every democracy is a republic. Great Britain, for example,

is a democracy but not a republic because it has a constitutional monarch

as its head of state.

What are the major types of government?

Characteristics of Democracy

Today some nations of the world misuse the word democracy.

Many countries call their governments “democratic” or “republican” whether

they really are or not. The government of North Korea, for example,

is an oligarchy, because a small number of Communist Party leaders run

the government. Yet their country is called the Democratic People’s

Republic of Korea. A true democratic government, as opposed to one

that only uses the term democratic in its name, has characteristics that

distinguish it from other forms of government.

Individual Liberty

No individual, of course, can be completely free to do

absolutely anything he or she wants. That would result in chaos.

Rather, democracy requires that all people be as free as possible to develop

their own capacities. Government in a democracy works to promote

the kind of equality in which all people have an equal opportunity to develop

their talents to the fullest extent possible.

Majority Rule with Minority Rights

Democracy also requires that government decisions be based

on majority rule. In a democracy people usually accept decisions

made by the majority of voters in a free election. Representative

democracy means that laws enacted in the legislatures represent the will

of the majority of lawmakers. Because these lawmakers are elected

by the people, the laws are accepted by the people.

At the same time, the American concept of democracy includes

a concern about the possible tyranny of the majority. The Constitution

helps ensure that the rights of the minority will be protected.

Respect for minority rights can be difficult to maintain,

especially when society is under great stress. For example, during

World War II, the government imprisoned more than 100,000 Japanese Americans

in relocation camps because it feared they would be disloyal. The

relocation program caused severe hardships for many Japanese Americans

and deprived them of their basic liberties. Even so, the program

was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1944 in Korematsu v. United States

1 and in two similar cases.

Endo v. United States

The Supreme Court, however, upheld the rights of Mitsuye

Endo in 1944. A native-born citizen, Endo was fired from a California

state job in 1942 and sent to a relocation center. Her lawyer challenged

the War Relocation board’s right to detain a loyal American citizen.

The case finally reached the Supreme Court in 1944.

On the day after the exclusionary order was revoked by

the military commander, the Court ruled that Mitsuye Endo could no longer

be held in custody. Justice Frank Murphy wrote:

“Detention in Relocation Centers of people

of Japanese ancestry regardless of loyalty is not only unauthorized by

Congress or the Executive, but is another example of the unconstitutional

resort to racism inherent in the entire evacuation program. ... Racial

discrimination of this nature bears no reasonable relation to military

necessity and is utterly foreign to the ideals and traditions of American

people.”

—Justice Frank Murphy, 1944

In recent years the wartime relocation program has been

criticized as a denial of individual rights and as proof that tyranny can

occur in even the most democratic societies. In 1988 Congress acknowledged

the “grave injustice” of the relocation experience and offered payments

of $20,000 to those Japanese Americans still living who had been relocated.

Free Elections

As we have seen, democratic governments receive their

legitimacy by the consent of the governed. The authority to create

and run the government rests with the people. All genuine democracies

have free and open elections. Free elections give people the chance

to choose their leaders and to voice their opinions on various issues.

Free elections also help ensure that public officials pay attention to

the wishes of the people.

In a democracy several characteristics mark free elections.

First, everyone’s vote carries the same weight—a principle often expressed

in the phrase “one person, one vote.” Second, all candidates have

the right to express their views freely, giving voters access to competing

ideas. Third, citizens are free to help candidates or support issues.

Fourth, the legal requirements for voting, such as age, residence, and

citizenship, are kept to a minimum. Thus, racial, ethnic, religious,

or other discriminatory tests cannot be used to restrict voting.

Fifth, citizens may vote freely by secret ballot, without coercion or fear

of punishment for their voting decisions.

Competing Political Parties

Political parties are an important element of democratic

government. A political party is a group of individuals with

broad common interests who organize to nominate candidates for office,

win elections, conduct government, and determine public policy. In

the United States, while any number of political parties may compete, a

two-party system in which the Republicans and the Democrats have become

the major political parties has developed. Rival parties help make

elections meaningful.

They give voters a choice among candidates. They

also help simplify and focus attention on key issues for voters.

Finally, in democratic countries, the political party or parties that are

out of power serve as a “loyal opposition.” That is, by criticizing the

policies and actions of the party in power, they can help make those in

power more responsible to the people.

What are the characteristics

of a democracy?

The Soil of Democracy

Historically, few nations have practiced democracy.

One reason may be that real democracy seems to require a special environment.

Democratic government is more likely to succeed in countries which to some

degree meet five general criteria that reflect the quality of life of citizens.

Active Citizen Participation

Democracy requires citizens who are willing to participate

in civic life. Countries in which citizens are able to inform themselves

about issues, to vote in elections, to serve on juries, to work for candidates,

and to run for government office are more likely to maintain a strong democracy

than countries where citizens do not participate fully in their government.

A Favorable Economy

Democracy succeeds more in countries that do not have

extremes of wealth and poverty and that have a large middle class.

The opportunity to control one’s economic decisions provides a base for

making independent political decisions. In the United States this

concept is called free enterprise. If people do not have control

of their economic lives, they will not likely be free to make political

decisions.

Countries with stable, growing economies seem better able

to support democratic government. In the past, autocrats who promised

citizens jobs and food have toppled many democratic governments during

times of severe economic depression. People who are out of work or

unable to feed their families often become more concerned about security

than about voting or exercising other political rights.

Widespread Education

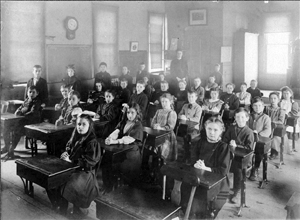

| Democracy is more likely to succeed in countries with

an educated public. The debate over public education in America was

settled in the 1830s. For example, in 1835 Pennsylvania voted to

fund public schools. Thaddeus Stevens, speaking to the Pennsylvania

state legislature in favor of the funding legislation, said: |

|

|

“If an elective republic is to endure for

any great length of time, every elector must have sufficient information...

to direct wisely the legislature, the ambassadors, and the executive of

the nation. ... [I]t is the duty of government to see that the means

of information be diffused to every citizen.”

—Thaddeus Stevens, April 1835

Strong Civil Society

Democracy is not possible without a civil society,

a complex network of voluntary associations, economic groups, religious

organizations, and many other kinds of groups that exist independently

of government. The United States has thousands of such organizations—the

Red Cross, the Humane Society, the Sierra Club, the National Rifle Association,

your local church and newspaper, labor unions, and business groups.

These organizations give citizens a way to make their views known to government

officials and the general public. They also give citizens a means

to take responsibility for protecting their rights, and they give everyone

a chance to learn about democracy by participating in it.

A Social Consensus

Democracy also prospers where most people accept democratic

values such as individual liberty and equality for all. Such countries

are said to have a social consensus. There also must be general

agreement about the purpose and limits of government.

History shows that conditions in the American colonies

favored the growth of democracy. Many individuals had an opportunity

to get ahead economically. The American colonists were among the

most educated people of the world at the time. Thomas Jefferson remarked

that Americans

“... seem to have deposited the monarchial

and taken up the republican government with as much ease as... [they] would

throwing off an old and putting on a new suit of clothes.”

—Thomas Jefferson, 1776

The English heritage provided a consensus of political

and social values. In time, the benefits of democracy would extend

to all Americans.

What are the requirements of

a democratic society? |