The Giant Cities of Bashan and Syria’s Holy Places

Rev. J. L. Porter D. D.

LONDON: T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW;

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK

1877

Pages: 11 - 29

|

|

I.

"All Bashan, unto Salchah and Edrei, cities of the kingdom of Og in Bashan. For only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the giants; behold, his bedstead was a bedstead of iron; is it not in Rabbath of the children of Ammon? nine cubits the length thereof, and four cubits the breadth of it, after the cubit of a man. ... And the rest of Gilead, and all Bashan, the kingdom of Og, gave I unto the half tribe of Manasseh; all the region of Argob, with all Bashan, which was called the land of giants." - DEUT. 3:10-13.

HISTORICAL NOTICES.

BASHAN is the land of

sacred romance. From the remotest historic period down to our own day

there has ever been something of mystery and of strange wild interest

connected with that old kingdom. In the memorable raid of the Arab

chiefs of Mesopotamia into Eastern and Central Palestine, we read that

the "Rephaim in Ashteroth-Karnaim" bore the first brunt of the onset. The Rephaim, - that is, "the giants,"

for such is the meaning of the name, men of stature, beside whom the

Jewish spies said long afterwards that they were as grasshoppers (Num.

13:33). These were the aboriginal inhabitants of Bashan,

and probably of the greater part of Canaan. Most of them died out, or

were exterminated at a very early period; but a few remarkable

specimens of the race - such as Goliath, and Sippai, and Lahmi

(1 Chron. 20) - were the terror of the Israelites, and the champions of

their foes, as late as the time of David; - and, strange to say,

traditionary memorials of these primeval giants

exist even now in almost every section of Palestine, in the form of

graves of enormous dimensions, - as the grave of Abel, near Damascus, thirty feet long; that of Seth, in Anti-Lebanon, about the same size; and that of Noah, in Lebanon, which measures no less than seventy yards! The capital and stronghold of the Rephaim in Bashan

was Ashteroth-Karnaim; so called from the goddess there worshipped, -

the mysterious "two-horned Astarte." We shall presently see, if my

readers will accompany me in my proposed tour, that the cities built

and occupied some forty centuries ago by these old giants

exist even yet. I have traversed their streets; I have opened the doors

of their houses; I have slept peacefully in their long-deserted halls.

We shall see, too, that among the massive ruins of these wonderful cities lie sculptured images of Astarte, with the crescent moon, which gave her the name Carnaim,

upon her brow. Of one of these mutilated statues I took a sketch in the

city of Kenath; and in the same place I bought from a shepherd an old

coin with the full figure of the goddess stamped upon it.

Four hundred years after the incursion of Chedorlaomer and his allies, another and a far more formidable enemy, emerging from the southern deserts, suddenly appeared on the borders of Bashan. Sihon, the warlike king of the Amorites, who reigned in Heshbon, had tried in vain to bar their progress. The rich plains, and wooded hills, and noble pasture-lands of Bashan offered a tempting prospect to the shepherd tribes of Israel. They came not on a sudden raid, like the Nomadic Arabs of the desert; they aimed at a complete conquest, and a permanent settlement. The aboriginal Rephaim were now all but extinct: "Only Og, king of Bashan, remained of the remnant of the giants." The last of his race in this region, he was still the ruler of his country; and the whole Amorite inhabitants, from Hermon to the Jabbok, and from the Jordan to the desert, acknowledged the supremacy of this giant warrior. Og resolved to defend his country. It was a splendid inheritance, and he would not resign it without a struggle. Collecting his forces, he marshalled them on the broad plain before Edrei. We have no details of the battle; but, doubtless, the Amorites and their leader fought bravely for country and for life. It was in vain; a stronger than human arm warred for Israel. Og’s army was defeated, and he himself slain. It would seem that the Ammonites, like the Bedawźn of the present day, followed in the wake of the Israelitish army; and after the defeat and flight of the Amorites, pillaged their deserted capital, Edrei, and carried off as a trophy the iron bedstead of Og. "Is it not," says the Jewish historian, "in Rabbath of the children of Ammon? nine cubits the length thereof, and four cubits the breadth of it, after the cubit of a man" (Deut. 3:11).

The conquest of Bashan, begun under the leadership of Moses in person, was completed by Jair, one of the most distinguished chiefs of the tribe of Manasseh. In narrating his achievements, the sacred historian brings out another remarkable fact connected with this kingdom of Bashan. In Argob, one of its little provinces, Jair took no less than sixty great cities, "fenced with high walls, gates, and bars; besides unwalled towns a great many" (Deut. 3:4, 5, 14). Such a statement seems all but incredible. It would not stand the arithmetic of Bishop Colenso for a moment. Often, when reading the passage, I used to think that some strange statistical mystery hung over it; for how could a province measuring not more than thirty miles by twenty support such a number of fortified cities, especially when the greater part of it was a wilderness of rocks? But mysterious, incredible as this seemed, on the spot, with my own eyes, I have seen that it is literally true. The cities are there to this day. Some of them retain the ancient names recorded in the Bible. The boundaries of Argob are as clearly defined by the hand of nature as those of our own island home. These ancient cities of Bashan contain probably the very oldest specimens of domestic architecture now existing in the world.

Though Bashan was conquered by the Israelites, and allotted to the half tribe of Manasseh, some of its native tribes were not exterminated. Leaving the fertile plains and rich pasturelands to the conquerors, these took refuge in the rocky recesses of Argob, and amid the mountain fastnesses of Hermon. "The Geshurites and the Maacathites," Joshua tells us, "dwell among the Israelites until this day" (13:13). The former made their home among the rocks of Argob. David, in some of his strange wanderings, met with, and married the daughter of Talmai, their chief; and she became the mother of Absalom. The wild acts of his life were doubtless, to some extent, the result of maternal training; they were at least characteristic of the stock from which she sprung. After murdering his brother Amnon, he fled to his uncle in Geshur, and found a safe asylum there amid its natural fastnesses, until his father’s wrath was appeased. It is a remarkable fact, - and it shows how little change three thousand years have produced on this Eastern land, - that Bashan is still the refuge for all offenders. If a man can only reach it, no matter what may have been his crimes or his failings, he is safe; the officers of government dare not follow him, and the avenger of blood even turns away in despair. During a short tour in Bashan, I met more than a dozen refugees, who, like Absalom in Geshur, awaited in security some favourable turn of events.

Bashan was regarded by the poet-prophets of Israel as almost an earthly paradise. The strength and grandeur of its oaks (Ezek. 27:6), the beauty of its mountain scenery (Ps. 68:6), the unrivalled luxuriance of its pastures (Jer. 1:19), the fertility of its wide-spreading plains, and the excellence of its cattle (Ps. 22:12; Micah 7:14), - all supplied the sacred penmen with lofty imagery. Remnants of the oak forests still clothe the mountain-sides; the soil of the plains and the pastures on the downs are rich as of yore; and though the periodic raids of Arab tribes have greatly thinned the flocks and herds, as they have desolated the cities, yet such as remain, - the rams, and lambs, and goats, and bulls,- may be appropriately described in the words of Ezekiel, as "all of them fatlings of Bashan" (39:18).

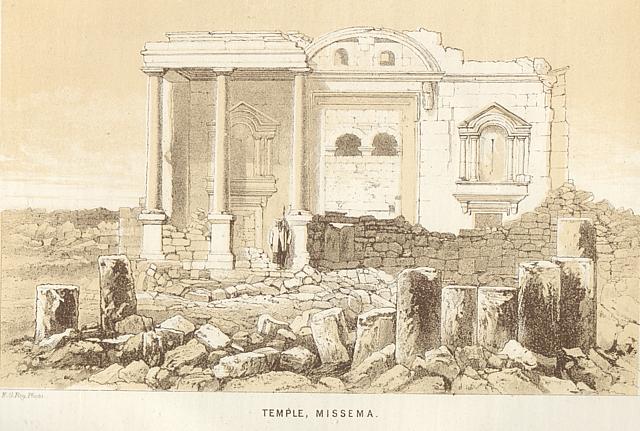

Lying on an exposed frontier, bordering on the restless and powerful kingdom of Damascus, and in the route of the warlike monarchs of Nineveh and Babylon, Bashan often experienced the horrors of war, and the desolating tide of conquest often rolled past and over it. The traces of ancient warfare are yet visible, as we shall see, in its ruinous fortresses; and we shall also see that it is now as much exposed as ever to the ravages of enemies. It was the first province of Palestine that fell before the Assyrian invaders; and its inhabitants were the first who sat and wept as captives by the banks of the rivers of the East. Bashan appears to have lost its unity with its freedom. It had been united under Og, and it remained united in possession of the half tribe of Manasseh; but after the captivity its very name, as a geographical term, disappears from history. When the Israelites were taken captive, the scattered remnants of the ancient tribes came back, - some from the parched plains of the great desert, some from the rocky defiles of Argob, and some from the heights and glens of Hermon, - and they tilled and occupied the whole country. Henceforth the name "Bashan" is never once mentioned by either sacred or classic writer; but the four provinces into which it was then rent are often referred to, - and these provinces were not themselves new. Gaulanitis is manifestly the territory of Golan, the ancient Hebrew city of refuge; Auranitis is only the Greek form of the Haurān of Ezekiel (48:16); Batanea, the name then given to the eastern mountain range, is but a corruption of Bashan; and Trachonitis, embracing that singularly wild and rocky district on the north, is just a Greek translation of the old Argob, "the stony." This last province is the only one mentioned in the New Testament. It formed part of the tetrachy of Philip, son of the great Herod (Luke 3:1). But though Bashan is not mentioned by name, it was the scene of a few of the most interesting events of New Testament history. It was down the western slopes of Bashan’s high table-land that the demons, expelled by Jesus from the poor man, chased the herd of swine into the Sea of Galilee. It was on the grassy slopes of Bashan’s hills that the multitudes were twice miraculously fed by the merciful Saviour. And that "high mountain," to which He led Peter, and James, and John, and on whose summit they beheld the glories of the transfiguration, was that very Hermon which forms the boundary of Bashan. And the sacred history of this old kingdom does not end here. Paul travelled through it on his way to Damascus; and, after his conversion, Bashan, which then formed the principal part of the kingdom of Arabia, was the first field of his labours as an apostle of Jesus. "When it pleased God," he tells us, "who separated me from my mother’s womb, and called me by his grace, to reveal his Son in me, that I might preach him among the heathen; immediately I conferred not with flesh and blood: neither went I up to Jerusalem to them which were apostles before me; but I went into Arabia" (Gal. 1:15-17). His mission to Arabia, or to Bashan, seems to have been eminently successful; and that Church, which may be called the first-fruits of his labours, made steady progress. In the fourth century nearly the whole inhabitants were Christian; heathen temples were converted into churches, and new churches were built in every town and village. At that period there were no fewer than thirty-three bishoprics in the single ecclesiastical province of Arabia. The Christians are now nearly all gone; but their churches, as we shall see, are there still, - two or three turned into mosques, but the vast majority of them standing desolate in deserted cities. Noble structures some of them are, with marble colonnades and stately porticos, showing us alike the wealth and the taste of their founders, and now remaining almost perfect, as if awaiting the influx of a new Christian population. There was something to me inexpressibly mournful in passing from the silent street into the silent church; and specially in reading, as I often read, Greek inscriptions over the doors, telling how such an one, at such a date, had consecrated this building, formerly a temple of Jupiter, or Venus, or Astarte, as the case might be, to the worship of the Triune God, and had called it by the name of the blessed saint or martyr So-and-so. Now there are no worshippers in those churches and the people who for twelve centuries have held supreme authority in the land, have been the constant and ruthless persecutors of Christians and Christianity. But their power is on the wane; their reign is well-nigh at an end; and the time is not far distant when Christian influence, and power, and industry, shall again repeople the deserted cities, and fill the vacant churches, and cultivate the desolate fields of Palestine.

The foregoing notices will show my readers that Bashan is, in many respects, among the most interesting of the provinces of Palestine. It is comparatively unknown, besides, Western Palestine is traversed every year; it forms a necessary part of the Grand Tour, and it has been described in scores of volumes. But the travellers who have hitherto succeeded in exploring Bashan scarcely amount to half-a-dozen; and the state of the country is so unsettled, and many of the people who inhabit it are so hostile to Europeans, and, in fact, to strangers in general, that there seems to be but little prospect of an increase of tourist in that region. This very isolation of Bashan added immensely to the charm and instructiveness of my visit. Both land and people remain thoroughly Oriental. Nowhere else is patriarchal life so fully or so strikingly exemplified. The social state of the country and the habits of the people are just what they were in the days of Abraham or Job. The raids of the eastern tribes are as frequent and as devastating now as they were then. The flocks of a whole village are often swept away in a single incursion, and the fruits of a whole harvest carried off in a single night. The arms used are, with the exception of a few muskets, similar to those with which Chedorlaomer conquered the Rephaim. The implements of husbandry, too, are as rude and as simple as they were when Isaac cultivated the valley of Gerar. And the hospitality is everywhere as profuse and as genuine as that which Abraham exercised in his tents at Mamre. I could scarcely get over the feeling, as I rode across the plains of Bashan and climbed the wooded hills through the oak forests, and saw the primitive ploughs and yokes of oxen and goads, and heard the old Bible salutations given by every passer-by, and received the urgent invitations to rest and eat at every village and hamlet, and witnessed the killing of the kid or lamb, and the almost incredible despatch with which it is cooked and served to the guests, - I could scarcely get over the feeling, I say, that I had been somehow spirited away back thousands of years, and set down in the land of Nod, or by the patriarch’s tents at Beersheba. Common life in Bashan I found to be a constant enacting of early Bible stories. Western Palestine has been in a great measure spoiled by travellers. In the towns frequented by tourists, and in their usual lines of route, I always found a miserable parody of Western manners, and not unfrequently of Western dress and language; but away in this old kingdom one meets with nothing in dress, language, or manners, save the stately and instructive simplicity of patriarchal times.

Another peculiarity of Bashan I cannot refrain from communicating to my readers. The ancient cities and even the villages of Western Palestine have been almost annihilated; with the exception of Jerusalem, Hebron, and two or three others, not one stone has been left upon another. In some cases we can scarcely discover the exact spot where a noted city stood, so complete has been the desolation. Even in Jerusalem itself only a very few vestiges of the ancient buildings remain: the Tower of David, portions of the wall of the Temple area, and one or two other fragments, - just enough to form the subject of dispute among antiquaries. Zion is "ploughed like a field." I have seen the plough at work on it, and with the hand that writes these lines I have plucked ears of corn in the fields of Zion. I have pitched my tent on the site of ancient Tyre, and searched, but searched in vain, for a single trace of its ruins. Then, but not till then, did I realize the full force and truth of the prophetic denunciation upon it: "Thou shalt be sought for, yet shalt thou never be found again" (Ezek. 26:21). The very ruins of Capernaum - that city which, in our Lord’s day, was "exalted unto heaven" - have been so completely obliterated, that the question of its site never has been, and probably never will be, definitely settled. And these are not solitary cases: Jericho has disappeared; Bethel is "come to nought" (Amos 5:5); Samaria is "as an heap of the field, as plantings of a vineyard" (Micah 1:6). The state of Bashan is totally different: it is literally crowded with towns and large villages; and though the vast majority of them are deserted, they are not ruined. I have more than once entered a deserted city in the evening, taken possession of a comfortable house, and spent the night in peace. Many of the houses in the ancient cities of Bashan are perfect, as if only finished yesterday. The walls are sound, the roofs unbroken, the doors, and even the window-shutters in their places. Let not my readers think that I am transcribing a passage from the "Arabian Nights." I am relating sober facts; I am simply telling what I have seen, and what I purpose just now more fully to describe. "But how," you ask me, "can we account for the preservation of ordinary dwellings in a land of ruins? If one of our modern English cities were deserted for a millennium, there would scarcely be a fragment of a wall standing." The reply is easy enough.

The houses of Bashan are not ordinary houses. Their walls are from five to eight feet thick, built of large squared blocks of basalt; the roofs are formed of slabs of the same material, hewn like planks, and reaching from wall to wall; the very doors and window-shutters are of stone, hung upon pivots projecting above and below. Some of these ancient cities have from two to five hundred houses still perfect, but not a man to dwell in them. On one occasion, from the battlements of the Castle of Salcah, I counted some thirty towns and villages, dotting the surface of the vast plain, many of them almost as perfect as when they were built, and yet for more than five centuries there has not been a single inhabitant in one of them. It may easily be imagined with what feelings I read on that day, and on that spot, the remarkable words of Moses: "The generation to come of your children that shall rise up after you, and the stranger that shall come from a far land, shall say when they see the plagues of this land, even all nations shall say, Wherefore hath the Lord done this unto this land? what meaneth the heat of this great anger?"

My readers are now prepared, I trust, to make a pleasant and profitable excursion to the giant cities of Bashan. I shall promise not to make too large a demand upon their time and patience, and yet to give them a tolerably clear and full view of one of the most interesting countries in the world.

After riding about seven miles, during which we passed straggling groups of men - some on foot, some on horses and, donkeys, and some on camels, most of them dressed like our guide, and all hurrying on in the same direction as ourselves - we reached the eastern extremity of the Black Mountains, and found ourselves on the side of a narrow green vale, through the centre of which flows the river Pharpar. A bridge here spans the stream; and beyond it, in the rich meadows, the Haurān Caravan was being marshalled. Up to this point the road is safe, and may be travelled almost at any time; but on crossing the Awaj, we enter the domains of the Bedawīn, whose law is the sword, and whose right is might. Our further progress was liable to be disputed at any moment. The attacks of the Bedawīn, when made, are sudden and impetuous; and resistance, to be effectual, must be prompt and decided. During the winter season, this eastern route is in general pretty secure, as the Arab tribes have their encampments far distant on the banks of the Euphrates, or in the interior of the desert; but the war between the Druses and the government, which had just been concluded, had drawn these daring marauders from their customary haunts, and they endured the rain and cold of the Syrian frontier in the hope of plunder. All seemed fully aware of this, and appeared to feel, here as elsewhere, that the hand of the Ishmaelite is against every man. Consequently, stragglers hurried up and fell into the ranks; bales and packages on mules and camels were re-arranged and more carefully adjusted; muskets and pistols were examined, and cartridges got into a state of readiness; armed men were placed in something like order along the sides of the file of animals; and a few horsemen were sent on in front, to scour the neighbouring hills and the skirts of the great plain beyond, so as to prevent surprise. A number of Druses who here joined the caravan, and who were easily distinguished by their snow-white turbans, and bold, manly bearing, appeared to take the chief direction in these warlike preparations, though, as the caravan was mainly made up of Christians, one of themselves, called Mūsa, was the nominal leader. It was a strange and exciting scene, and one would have thought that any attempt to reduce such a refractory and heterogeneous multitude of men and animals to anything like order would be absolutely useless. Some of the camels and donkeys breaking loose, scattered their loads over the plain, and spread confusion all round them; others growled, and kicked, and brayed; drivers shouted and gesticulated; men and boys ran through the crowd, asking for missing brothers or companions; horsemen galloped from group to group, entreating and threatening by turns. At length, however, the order was given to march. It passed along from front to rear, and the next moment every sound was hushed; the very beasts seemed to comprehend its meaning, for they fell quietly into their places, and the long files, now four and five abreast, began to move over the grassy plain with a stillness which was almost painful.

Leaving the fertile valley of the Pharpar, and crossing a low, bleak ridge, we entered one of the dreariest regions I had hitherto seen in Syria. A reach of rolling table-land extended for several miles on each side-shut in on the right by black hills, and on the left, by bare rugged banks. Not a house, nor a tree, nor a green shrub, nor a living creature, was within the range of vision. Loose black stones and boulders of basalt were strewn thickly over the whole surface, and here and there thrown into rude heaps; but whether by the hands of man, or by some freak of nature, seemed doubtful. For nearly two hours we wound our weary way through this wilderness; now listening to the stories of Mūsa, and now following him to the top of some hillock, in the hope of getting a peep at a more inviting landscape. At length we came to the brow of a short descent leading into a green meadow, with the traces of an old camp at one side round a little fountain, near which were some tombs with rude headstones. We were told that this is a favourite camping-ground of the Anezeh during the spring. Immediately beyond the meadow a plain opened up before us, stretching on the east and west far as the eye could see, and southward reaching to the base of the Haurān mountains. It is flat as a lake, covered with deep, rich, black soil, without rock or stone, and, even at this early season, giving promise of luxuriant pasturage. Some conical tells are seen at intervals, rising up from its smooth surface, like rocky islets in the ocean. This is the plain of Bashan, and though now desolate and forsaken, it showed us how rich were the resources of that old kingdom.

With increased speed-but still in the deepest silence-the caravan swept onward over this noble plain. We could scarcely distinguish any track, though Mūsa assured us we were on the Sultāny, or "king’s highway." It seemed to us that his course was directed by a conical hill away on the southern horizon, rather than by any trace of a road on the plain itself. As we advanced, we began to notice a black line extending across the plain, in the distance in front. Gradually it became more and more defined, and, ere daylight waned, it seemed like a Cyclopean wall built in some bygone age, and afterwards shattered by an earthquake. Riding up to Mūsa, I asked what it was. "That," said he, "is the Lejah." Lejah is the name now given to the ancient province of Trachonitis; and this bank of shattered rocks turned out to be its northern border. The Lejah, as we shall see hereafter, is a vast field of basalt, placed in the midst of the fertile plain of Bashan. Its surface has an elevation of some thirty feet above the plain, and its border is everywhere as clearly defined by the broken cliffs as any shore-line. In fact, it strongly reminded me of some parts of the coast of Jersey. And this remarkable feature has not been overlooked in the topography of the Bible. Lejah, my readers will remember, corresponds to the ancient Argob. Now, in every instance in which that province is mentioned by the sacred historians, there is one descriptive word attached to it - chebel; which our translators have unfortunately rendered in one passage "region," and in another, "country" (Deut. 3:4, 13, 14; 1 Kings 4:13), but which means "a sharply-defined border, as if measured off by a rope" (chebel); and it thus describes, with singular accuracy and minuteness, the rocky rampart which encircles the Lejah.

I looked with no little interest round the apartment of which we had taken such unceremonious possession; but the light was so dim, and the walls, roof, and floor so black, that I could make out nothing satisfactorily. Getting a torch from one of the servants I lighted it, and proceeded to examine the mysterious mansion; for, though drenched with rain, and wearied with a twelve hours' ride, I could not rest. I felt an excitement such as I never before had experienced. I could scarcely believe in the reality of what I saw, and what I heard from my guides in reply to eager questions. The house seemed to have undergone little change from the time its old master had left it; and yet the thick nitrous crust on the. floor showed that it had been deserted for long ages. The walls were perfect, nearly five feet thick, built of large blocks of hewn stones, without lime or cement of any kind. The roof was formed of large slabs of the same black basalt, lying as regularly, and jointed as closely, as if the workmen had only just completed them. They measured twelve feet in length, eighteen inches in breadth, and six inches in thickness. The ends rested on a plain stone cornice, projecting about a foot from each side wall. The chamber was twenty feet long, twelve wide, and ten high. The outer door was a slab of stone, four and a half feet high, four wide, and eight inches thick. It hung upon pivots, formed of projecting parts of the slab, working in sockets in the lintel and threshold; and though so massive, I was able to open and shut it with ease. At one end of the room was a small window with a stone shutter. An inner door, also of stone, but of finer workmanship, and not quite so heavy as the other, admitted to a chamber of the same size and appearance. From it a much larger door communicated with a third chamber, to which there was a descent by a flight of stone steps. This was a spacious hall, equal in width to the two rooms, and about twenty-five feet long by twenty high. A semicircular arch was thrown across it, supporting the stone roof; and a gate so large that camels could pass in and out, opened on the street. The gate was of stone, and in its place; but some rubbish had accumulated on the threshold, and it appeared to have been open for ages. Here our horses were comfortably installed. Such were the internal arrangements of this strange old mansion. It had only one story; and its simple, massive style of architecture gave evidence of a very remote antiquity. On a large stone which formed the lintel of the gateway, there was a Greek inscription; but it was so high up, and my light so faint, that I was unable to decipher it, though I could see that the letters were of the oldest type. It is probably the same which was copied by Burckhardt, and which bears a date apparently equivalent to the year B.C. 306!

Owing to the darkness of the night, and the shortness of our stay, I was unable to ascertain, from personal observation, either the extent of Burāk, or the general character of its buildings; but the men who gathered round me, when I returned to my chamber, had often visited it. They said the houses were all like the one we occupied, only some smaller, and a few larger, and that there were no great buildings. Burāk stands on the north-east corner of the Lejah, and was thus one, of the frontier towns of ancient Argob. It is built upon rocks, and encompassed by rocks so wild and rugged as to render it a natural fortress.

After a few hours' rest the order for march was again given. We found our horses at the door, and mounting at once we followed Mūsa. The rain had ceased, the sky was clear, and the moon shone brightly, half revealing the savage features of the environs of Burāk. I can never forget that scene. Huge masses of shapeless rock rose up here and there among and around the houses, to the height of fifteen and twenty feet - their summits jagged, and their sides all shattered. Between them were pits and yawning fissures, as many feet in depth; while the flat surfaces of naked rock were thickly strewn with huge boulders of basalt. The narrow tortuous road by which Mūsa led us out was in places carried over chasms, and in places cut through cliffs. An ancient aqueduct ran alongside it, which, in former days, conveyed a supply of water from a neighbouring winter stream to the tanks and reservoirs from which the town gets its present name, Burāk ("the tanks"). A slow but fatiguing ride of an hour brought us out of this labyrinth of rocks, and over a torrent bed into a fine plain. We soon after passed the caravan, which had started some time before us; and, as there was no danger to be apprehended, we continued at a rapid pace southward. The dawn of morning showed us the rugged features and rocky border of the Lejah close upon our right, thickly studded with old towns and villages; while upon our left a fertile plain stretched away to the horizon. And here we observed with surprise, that there was not a trace of human habitation, except on the tops of the little conical hills which rise up at long intervals. This plain is the home of the Ishmaelite, who has always dwelt "in the presence (literally, in the face) of his brethren" (Gen. 16:12), and against whose bold incursions there never has been any effectual barrier except the munitions of rocks and the heights of hills.

We rode on. The hills of Bashan were close in front; their summits clothed with oak forests, and their sides studded with old towns. As we ascended them, the rock-fields of the Lejah were spread out on the right; and there, too, the ancient cities were thickly planted. Not less than thirty of the threescore cities of Argob were in view at one time on that day; their black houses and ruins half concealed by the black rocks amid which they are built, and their massive towers rising up here and there like the "keeps" of old Norman fortresses. How we longed to visit and explore them! But political reasons made it necessary we should, in the first place, pay our respects to one of the leading Druse chiefs. On them depended the success of our future researches. Without their protection we could not ride in safety a single mile through Haurān. I felt confident that protection would be cheerfully granted; still I thought it best not to draw bridle until we reached the town of Hiyāt, from whence, after a short pause to drink coffee with the Sheikh, who would not let us pass, we rode to the residence of Asad Amer, at Hit, where we met with a reception worthy of the hospitality of the old patriarchs.

Four hundred years after the incursion of Chedorlaomer and his allies, another and a far more formidable enemy, emerging from the southern deserts, suddenly appeared on the borders of Bashan. Sihon, the warlike king of the Amorites, who reigned in Heshbon, had tried in vain to bar their progress. The rich plains, and wooded hills, and noble pasture-lands of Bashan offered a tempting prospect to the shepherd tribes of Israel. They came not on a sudden raid, like the Nomadic Arabs of the desert; they aimed at a complete conquest, and a permanent settlement. The aboriginal Rephaim were now all but extinct: "Only Og, king of Bashan, remained of the remnant of the giants." The last of his race in this region, he was still the ruler of his country; and the whole Amorite inhabitants, from Hermon to the Jabbok, and from the Jordan to the desert, acknowledged the supremacy of this giant warrior. Og resolved to defend his country. It was a splendid inheritance, and he would not resign it without a struggle. Collecting his forces, he marshalled them on the broad plain before Edrei. We have no details of the battle; but, doubtless, the Amorites and their leader fought bravely for country and for life. It was in vain; a stronger than human arm warred for Israel. Og’s army was defeated, and he himself slain. It would seem that the Ammonites, like the Bedawźn of the present day, followed in the wake of the Israelitish army; and after the defeat and flight of the Amorites, pillaged their deserted capital, Edrei, and carried off as a trophy the iron bedstead of Og. "Is it not," says the Jewish historian, "in Rabbath of the children of Ammon? nine cubits the length thereof, and four cubits the breadth of it, after the cubit of a man" (Deut. 3:11).

The conquest of Bashan, begun under the leadership of Moses in person, was completed by Jair, one of the most distinguished chiefs of the tribe of Manasseh. In narrating his achievements, the sacred historian brings out another remarkable fact connected with this kingdom of Bashan. In Argob, one of its little provinces, Jair took no less than sixty great cities, "fenced with high walls, gates, and bars; besides unwalled towns a great many" (Deut. 3:4, 5, 14). Such a statement seems all but incredible. It would not stand the arithmetic of Bishop Colenso for a moment. Often, when reading the passage, I used to think that some strange statistical mystery hung over it; for how could a province measuring not more than thirty miles by twenty support such a number of fortified cities, especially when the greater part of it was a wilderness of rocks? But mysterious, incredible as this seemed, on the spot, with my own eyes, I have seen that it is literally true. The cities are there to this day. Some of them retain the ancient names recorded in the Bible. The boundaries of Argob are as clearly defined by the hand of nature as those of our own island home. These ancient cities of Bashan contain probably the very oldest specimens of domestic architecture now existing in the world.

Though Bashan was conquered by the Israelites, and allotted to the half tribe of Manasseh, some of its native tribes were not exterminated. Leaving the fertile plains and rich pasturelands to the conquerors, these took refuge in the rocky recesses of Argob, and amid the mountain fastnesses of Hermon. "The Geshurites and the Maacathites," Joshua tells us, "dwell among the Israelites until this day" (13:13). The former made their home among the rocks of Argob. David, in some of his strange wanderings, met with, and married the daughter of Talmai, their chief; and she became the mother of Absalom. The wild acts of his life were doubtless, to some extent, the result of maternal training; they were at least characteristic of the stock from which she sprung. After murdering his brother Amnon, he fled to his uncle in Geshur, and found a safe asylum there amid its natural fastnesses, until his father’s wrath was appeased. It is a remarkable fact, - and it shows how little change three thousand years have produced on this Eastern land, - that Bashan is still the refuge for all offenders. If a man can only reach it, no matter what may have been his crimes or his failings, he is safe; the officers of government dare not follow him, and the avenger of blood even turns away in despair. During a short tour in Bashan, I met more than a dozen refugees, who, like Absalom in Geshur, awaited in security some favourable turn of events.

Bashan was regarded by the poet-prophets of Israel as almost an earthly paradise. The strength and grandeur of its oaks (Ezek. 27:6), the beauty of its mountain scenery (Ps. 68:6), the unrivalled luxuriance of its pastures (Jer. 1:19), the fertility of its wide-spreading plains, and the excellence of its cattle (Ps. 22:12; Micah 7:14), - all supplied the sacred penmen with lofty imagery. Remnants of the oak forests still clothe the mountain-sides; the soil of the plains and the pastures on the downs are rich as of yore; and though the periodic raids of Arab tribes have greatly thinned the flocks and herds, as they have desolated the cities, yet such as remain, - the rams, and lambs, and goats, and bulls,- may be appropriately described in the words of Ezekiel, as "all of them fatlings of Bashan" (39:18).

Lying on an exposed frontier, bordering on the restless and powerful kingdom of Damascus, and in the route of the warlike monarchs of Nineveh and Babylon, Bashan often experienced the horrors of war, and the desolating tide of conquest often rolled past and over it. The traces of ancient warfare are yet visible, as we shall see, in its ruinous fortresses; and we shall also see that it is now as much exposed as ever to the ravages of enemies. It was the first province of Palestine that fell before the Assyrian invaders; and its inhabitants were the first who sat and wept as captives by the banks of the rivers of the East. Bashan appears to have lost its unity with its freedom. It had been united under Og, and it remained united in possession of the half tribe of Manasseh; but after the captivity its very name, as a geographical term, disappears from history. When the Israelites were taken captive, the scattered remnants of the ancient tribes came back, - some from the parched plains of the great desert, some from the rocky defiles of Argob, and some from the heights and glens of Hermon, - and they tilled and occupied the whole country. Henceforth the name "Bashan" is never once mentioned by either sacred or classic writer; but the four provinces into which it was then rent are often referred to, - and these provinces were not themselves new. Gaulanitis is manifestly the territory of Golan, the ancient Hebrew city of refuge; Auranitis is only the Greek form of the Haurān of Ezekiel (48:16); Batanea, the name then given to the eastern mountain range, is but a corruption of Bashan; and Trachonitis, embracing that singularly wild and rocky district on the north, is just a Greek translation of the old Argob, "the stony." This last province is the only one mentioned in the New Testament. It formed part of the tetrachy of Philip, son of the great Herod (Luke 3:1). But though Bashan is not mentioned by name, it was the scene of a few of the most interesting events of New Testament history. It was down the western slopes of Bashan’s high table-land that the demons, expelled by Jesus from the poor man, chased the herd of swine into the Sea of Galilee. It was on the grassy slopes of Bashan’s hills that the multitudes were twice miraculously fed by the merciful Saviour. And that "high mountain," to which He led Peter, and James, and John, and on whose summit they beheld the glories of the transfiguration, was that very Hermon which forms the boundary of Bashan. And the sacred history of this old kingdom does not end here. Paul travelled through it on his way to Damascus; and, after his conversion, Bashan, which then formed the principal part of the kingdom of Arabia, was the first field of his labours as an apostle of Jesus. "When it pleased God," he tells us, "who separated me from my mother’s womb, and called me by his grace, to reveal his Son in me, that I might preach him among the heathen; immediately I conferred not with flesh and blood: neither went I up to Jerusalem to them which were apostles before me; but I went into Arabia" (Gal. 1:15-17). His mission to Arabia, or to Bashan, seems to have been eminently successful; and that Church, which may be called the first-fruits of his labours, made steady progress. In the fourth century nearly the whole inhabitants were Christian; heathen temples were converted into churches, and new churches were built in every town and village. At that period there were no fewer than thirty-three bishoprics in the single ecclesiastical province of Arabia. The Christians are now nearly all gone; but their churches, as we shall see, are there still, - two or three turned into mosques, but the vast majority of them standing desolate in deserted cities. Noble structures some of them are, with marble colonnades and stately porticos, showing us alike the wealth and the taste of their founders, and now remaining almost perfect, as if awaiting the influx of a new Christian population. There was something to me inexpressibly mournful in passing from the silent street into the silent church; and specially in reading, as I often read, Greek inscriptions over the doors, telling how such an one, at such a date, had consecrated this building, formerly a temple of Jupiter, or Venus, or Astarte, as the case might be, to the worship of the Triune God, and had called it by the name of the blessed saint or martyr So-and-so. Now there are no worshippers in those churches and the people who for twelve centuries have held supreme authority in the land, have been the constant and ruthless persecutors of Christians and Christianity. But their power is on the wane; their reign is well-nigh at an end; and the time is not far distant when Christian influence, and power, and industry, shall again repeople the deserted cities, and fill the vacant churches, and cultivate the desolate fields of Palestine.

The foregoing notices will show my readers that Bashan is, in many respects, among the most interesting of the provinces of Palestine. It is comparatively unknown, besides, Western Palestine is traversed every year; it forms a necessary part of the Grand Tour, and it has been described in scores of volumes. But the travellers who have hitherto succeeded in exploring Bashan scarcely amount to half-a-dozen; and the state of the country is so unsettled, and many of the people who inhabit it are so hostile to Europeans, and, in fact, to strangers in general, that there seems to be but little prospect of an increase of tourist in that region. This very isolation of Bashan added immensely to the charm and instructiveness of my visit. Both land and people remain thoroughly Oriental. Nowhere else is patriarchal life so fully or so strikingly exemplified. The social state of the country and the habits of the people are just what they were in the days of Abraham or Job. The raids of the eastern tribes are as frequent and as devastating now as they were then. The flocks of a whole village are often swept away in a single incursion, and the fruits of a whole harvest carried off in a single night. The arms used are, with the exception of a few muskets, similar to those with which Chedorlaomer conquered the Rephaim. The implements of husbandry, too, are as rude and as simple as they were when Isaac cultivated the valley of Gerar. And the hospitality is everywhere as profuse and as genuine as that which Abraham exercised in his tents at Mamre. I could scarcely get over the feeling, as I rode across the plains of Bashan and climbed the wooded hills through the oak forests, and saw the primitive ploughs and yokes of oxen and goads, and heard the old Bible salutations given by every passer-by, and received the urgent invitations to rest and eat at every village and hamlet, and witnessed the killing of the kid or lamb, and the almost incredible despatch with which it is cooked and served to the guests, - I could scarcely get over the feeling, I say, that I had been somehow spirited away back thousands of years, and set down in the land of Nod, or by the patriarch’s tents at Beersheba. Common life in Bashan I found to be a constant enacting of early Bible stories. Western Palestine has been in a great measure spoiled by travellers. In the towns frequented by tourists, and in their usual lines of route, I always found a miserable parody of Western manners, and not unfrequently of Western dress and language; but away in this old kingdom one meets with nothing in dress, language, or manners, save the stately and instructive simplicity of patriarchal times.

Another peculiarity of Bashan I cannot refrain from communicating to my readers. The ancient cities and even the villages of Western Palestine have been almost annihilated; with the exception of Jerusalem, Hebron, and two or three others, not one stone has been left upon another. In some cases we can scarcely discover the exact spot where a noted city stood, so complete has been the desolation. Even in Jerusalem itself only a very few vestiges of the ancient buildings remain: the Tower of David, portions of the wall of the Temple area, and one or two other fragments, - just enough to form the subject of dispute among antiquaries. Zion is "ploughed like a field." I have seen the plough at work on it, and with the hand that writes these lines I have plucked ears of corn in the fields of Zion. I have pitched my tent on the site of ancient Tyre, and searched, but searched in vain, for a single trace of its ruins. Then, but not till then, did I realize the full force and truth of the prophetic denunciation upon it: "Thou shalt be sought for, yet shalt thou never be found again" (Ezek. 26:21). The very ruins of Capernaum - that city which, in our Lord’s day, was "exalted unto heaven" - have been so completely obliterated, that the question of its site never has been, and probably never will be, definitely settled. And these are not solitary cases: Jericho has disappeared; Bethel is "come to nought" (Amos 5:5); Samaria is "as an heap of the field, as plantings of a vineyard" (Micah 1:6). The state of Bashan is totally different: it is literally crowded with towns and large villages; and though the vast majority of them are deserted, they are not ruined. I have more than once entered a deserted city in the evening, taken possession of a comfortable house, and spent the night in peace. Many of the houses in the ancient cities of Bashan are perfect, as if only finished yesterday. The walls are sound, the roofs unbroken, the doors, and even the window-shutters in their places. Let not my readers think that I am transcribing a passage from the "Arabian Nights." I am relating sober facts; I am simply telling what I have seen, and what I purpose just now more fully to describe. "But how," you ask me, "can we account for the preservation of ordinary dwellings in a land of ruins? If one of our modern English cities were deserted for a millennium, there would scarcely be a fragment of a wall standing." The reply is easy enough.

The houses of Bashan are not ordinary houses. Their walls are from five to eight feet thick, built of large squared blocks of basalt; the roofs are formed of slabs of the same material, hewn like planks, and reaching from wall to wall; the very doors and window-shutters are of stone, hung upon pivots projecting above and below. Some of these ancient cities have from two to five hundred houses still perfect, but not a man to dwell in them. On one occasion, from the battlements of the Castle of Salcah, I counted some thirty towns and villages, dotting the surface of the vast plain, many of them almost as perfect as when they were built, and yet for more than five centuries there has not been a single inhabitant in one of them. It may easily be imagined with what feelings I read on that day, and on that spot, the remarkable words of Moses: "The generation to come of your children that shall rise up after you, and the stranger that shall come from a far land, shall say when they see the plagues of this land, even all nations shall say, Wherefore hath the Lord done this unto this land? what meaneth the heat of this great anger?"

My readers are now prepared, I trust, to make a pleasant and profitable excursion to the giant cities of Bashan. I shall promise not to make too large a demand upon their time and patience, and yet to give them a tolerably clear and full view of one of the most interesting countries in the world.

THE CARAVAN.

On a bright and balmy morning in February, a party of seven cavaliers defiled from the East Gate of Damascus, rode for half-an-hour among the orchards that skirt the old city, and then, turning to the left, struck out, along a broad beaten path through the open fields, in a south-easterly direction. The leader Was a wild-looking figure. His dress was a red cotton tunic or shirt, fastened round the waist by a broad leathern girdle. Over it was a loose jacket of dressed sheepskin, the wool inside. His feet and legs were bare. On his head was a flame-coloured handkerchief, fastened above by a coronet of black camel’s hair, which left the ends and long fringe to flow over his shoulders. He was mounted on an active, shaggy pony, with a pad for a saddle, and a hair halter for a bridle. Before him, across the back of his little steed, he carried a long rifle, his, only weapon. Immediately behind him, on powerful Arab horses, were three men in Western costume: one of these was the writer. Next came an Arab, who acted as dragoman or rather courier; and two servants on stout hacks brought up the rear. On gaining the beaten track, our guide struck into a sharp canter. The great city was soon left far behind, and, on turning, we could see its tall white minarets shooting up from the sombre - foliage, and thrown into bold relief by the dark background of Anti-Lebanon. The plain spread out on each side, smooth as a lake, covered with the delicate green of the young grain. Here and there were long belts and large clumps of dusky olives, from the midst of which rose the gray towers of a mosque or the white dome of a saint’s tomb. On the south the plain was shut in by a ridge of black, bare hills, appropriately named Jebel-el-Aswad, "the Black Mountains;" while away on the west, in the distance, Hermon rose in all its majesty, a pyramid of spotless snow. From whatever point one sees it, there are few landscapes in the world which, for richness and soft enchanting beauty, can be compared with the plain of Damascus.After riding about seven miles, during which we passed straggling groups of men - some on foot, some on horses and, donkeys, and some on camels, most of them dressed like our guide, and all hurrying on in the same direction as ourselves - we reached the eastern extremity of the Black Mountains, and found ourselves on the side of a narrow green vale, through the centre of which flows the river Pharpar. A bridge here spans the stream; and beyond it, in the rich meadows, the Haurān Caravan was being marshalled. Up to this point the road is safe, and may be travelled almost at any time; but on crossing the Awaj, we enter the domains of the Bedawīn, whose law is the sword, and whose right is might. Our further progress was liable to be disputed at any moment. The attacks of the Bedawīn, when made, are sudden and impetuous; and resistance, to be effectual, must be prompt and decided. During the winter season, this eastern route is in general pretty secure, as the Arab tribes have their encampments far distant on the banks of the Euphrates, or in the interior of the desert; but the war between the Druses and the government, which had just been concluded, had drawn these daring marauders from their customary haunts, and they endured the rain and cold of the Syrian frontier in the hope of plunder. All seemed fully aware of this, and appeared to feel, here as elsewhere, that the hand of the Ishmaelite is against every man. Consequently, stragglers hurried up and fell into the ranks; bales and packages on mules and camels were re-arranged and more carefully adjusted; muskets and pistols were examined, and cartridges got into a state of readiness; armed men were placed in something like order along the sides of the file of animals; and a few horsemen were sent on in front, to scour the neighbouring hills and the skirts of the great plain beyond, so as to prevent surprise. A number of Druses who here joined the caravan, and who were easily distinguished by their snow-white turbans, and bold, manly bearing, appeared to take the chief direction in these warlike preparations, though, as the caravan was mainly made up of Christians, one of themselves, called Mūsa, was the nominal leader. It was a strange and exciting scene, and one would have thought that any attempt to reduce such a refractory and heterogeneous multitude of men and animals to anything like order would be absolutely useless. Some of the camels and donkeys breaking loose, scattered their loads over the plain, and spread confusion all round them; others growled, and kicked, and brayed; drivers shouted and gesticulated; men and boys ran through the crowd, asking for missing brothers or companions; horsemen galloped from group to group, entreating and threatening by turns. At length, however, the order was given to march. It passed along from front to rear, and the next moment every sound was hushed; the very beasts seemed to comprehend its meaning, for they fell quietly into their places, and the long files, now four and five abreast, began to move over the grassy plain with a stillness which was almost painful.

Leaving the fertile valley of the Pharpar, and crossing a low, bleak ridge, we entered one of the dreariest regions I had hitherto seen in Syria. A reach of rolling table-land extended for several miles on each side-shut in on the right by black hills, and on the left, by bare rugged banks. Not a house, nor a tree, nor a green shrub, nor a living creature, was within the range of vision. Loose black stones and boulders of basalt were strewn thickly over the whole surface, and here and there thrown into rude heaps; but whether by the hands of man, or by some freak of nature, seemed doubtful. For nearly two hours we wound our weary way through this wilderness; now listening to the stories of Mūsa, and now following him to the top of some hillock, in the hope of getting a peep at a more inviting landscape. At length we came to the brow of a short descent leading into a green meadow, with the traces of an old camp at one side round a little fountain, near which were some tombs with rude headstones. We were told that this is a favourite camping-ground of the Anezeh during the spring. Immediately beyond the meadow a plain opened up before us, stretching on the east and west far as the eye could see, and southward reaching to the base of the Haurān mountains. It is flat as a lake, covered with deep, rich, black soil, without rock or stone, and, even at this early season, giving promise of luxuriant pasturage. Some conical tells are seen at intervals, rising up from its smooth surface, like rocky islets in the ocean. This is the plain of Bashan, and though now desolate and forsaken, it showed us how rich were the resources of that old kingdom.

With increased speed-but still in the deepest silence-the caravan swept onward over this noble plain. We could scarcely distinguish any track, though Mūsa assured us we were on the Sultāny, or "king’s highway." It seemed to us that his course was directed by a conical hill away on the southern horizon, rather than by any trace of a road on the plain itself. As we advanced, we began to notice a black line extending across the plain, in the distance in front. Gradually it became more and more defined, and, ere daylight waned, it seemed like a Cyclopean wall built in some bygone age, and afterwards shattered by an earthquake. Riding up to Mūsa, I asked what it was. "That," said he, "is the Lejah." Lejah is the name now given to the ancient province of Trachonitis; and this bank of shattered rocks turned out to be its northern border. The Lejah, as we shall see hereafter, is a vast field of basalt, placed in the midst of the fertile plain of Bashan. Its surface has an elevation of some thirty feet above the plain, and its border is everywhere as clearly defined by the broken cliffs as any shore-line. In fact, it strongly reminded me of some parts of the coast of Jersey. And this remarkable feature has not been overlooked in the topography of the Bible. Lejah, my readers will remember, corresponds to the ancient Argob. Now, in every instance in which that province is mentioned by the sacred historians, there is one descriptive word attached to it - chebel; which our translators have unfortunately rendered in one passage "region," and in another, "country" (Deut. 3:4, 13, 14; 1 Kings 4:13), but which means "a sharply-defined border, as if measured off by a rope" (chebel); and it thus describes, with singular accuracy and minuteness, the rocky rampart which encircles the Lejah.

THE DESERTED CITY.

The sun went down, and the short twilight was made shorter by heavy clouds which drifted across the face of the sky. A thick rain began to fall, which made the prospect of a night march or a bivouac equally unpleasant. Still I rode on through the darkness, striving to dispel gloomy forebodings by the stirring memory of Bashan’s ancient glory, and the thought that I was now treading its soil, and on my way to the great cities founded and inhabited four thousand years ago by the giant Rephaim. Before the darkness set in, Mūsa had pointed out to me the towers of three or four of these cities rising above the rocky barrier of the Lejah. How I strained my eyes in vain to pierce the deepening gloom! Now I knew that some of them must be close at hand. The sharp ring of my horse’s feet on pavement startled me. This was followed by painful stumbling over loose stones, and the twisting of his limbs among jagged rocks. The sky was black overhead; the ground black beneath; the rain was drifting in my face, so that nothing could be seen. A halt was called; and it was with no little pleasure I heard the order given for the caravan to rest till the moon rose. - "Is there any spot," I asked of an Arab at my side, "where we could get shelter from the rain?" "There is a house ready for you," he answered. "A house! Is there a house here?" "Hundreds of them; this is the town of Burāk." We were conducted up a rugged winding path, which seemed, so far as we could make out in the dark and by the motion of our horses, to be something like a ruinous staircase. At length the dark outline of high walls began to appear against the sky, and presently we entered a paved street. Here we were told to dismount and give our horses to the servants. An Arab struck a light, and, inviting us to follow, passed through a low, gloomy door, into a spacious chamber.I looked with no little interest round the apartment of which we had taken such unceremonious possession; but the light was so dim, and the walls, roof, and floor so black, that I could make out nothing satisfactorily. Getting a torch from one of the servants I lighted it, and proceeded to examine the mysterious mansion; for, though drenched with rain, and wearied with a twelve hours' ride, I could not rest. I felt an excitement such as I never before had experienced. I could scarcely believe in the reality of what I saw, and what I heard from my guides in reply to eager questions. The house seemed to have undergone little change from the time its old master had left it; and yet the thick nitrous crust on the. floor showed that it had been deserted for long ages. The walls were perfect, nearly five feet thick, built of large blocks of hewn stones, without lime or cement of any kind. The roof was formed of large slabs of the same black basalt, lying as regularly, and jointed as closely, as if the workmen had only just completed them. They measured twelve feet in length, eighteen inches in breadth, and six inches in thickness. The ends rested on a plain stone cornice, projecting about a foot from each side wall. The chamber was twenty feet long, twelve wide, and ten high. The outer door was a slab of stone, four and a half feet high, four wide, and eight inches thick. It hung upon pivots, formed of projecting parts of the slab, working in sockets in the lintel and threshold; and though so massive, I was able to open and shut it with ease. At one end of the room was a small window with a stone shutter. An inner door, also of stone, but of finer workmanship, and not quite so heavy as the other, admitted to a chamber of the same size and appearance. From it a much larger door communicated with a third chamber, to which there was a descent by a flight of stone steps. This was a spacious hall, equal in width to the two rooms, and about twenty-five feet long by twenty high. A semicircular arch was thrown across it, supporting the stone roof; and a gate so large that camels could pass in and out, opened on the street. The gate was of stone, and in its place; but some rubbish had accumulated on the threshold, and it appeared to have been open for ages. Here our horses were comfortably installed. Such were the internal arrangements of this strange old mansion. It had only one story; and its simple, massive style of architecture gave evidence of a very remote antiquity. On a large stone which formed the lintel of the gateway, there was a Greek inscription; but it was so high up, and my light so faint, that I was unable to decipher it, though I could see that the letters were of the oldest type. It is probably the same which was copied by Burckhardt, and which bears a date apparently equivalent to the year B.C. 306!

Owing to the darkness of the night, and the shortness of our stay, I was unable to ascertain, from personal observation, either the extent of Burāk, or the general character of its buildings; but the men who gathered round me, when I returned to my chamber, had often visited it. They said the houses were all like the one we occupied, only some smaller, and a few larger, and that there were no great buildings. Burāk stands on the north-east corner of the Lejah, and was thus one, of the frontier towns of ancient Argob. It is built upon rocks, and encompassed by rocks so wild and rugged as to render it a natural fortress.

After a few hours' rest the order for march was again given. We found our horses at the door, and mounting at once we followed Mūsa. The rain had ceased, the sky was clear, and the moon shone brightly, half revealing the savage features of the environs of Burāk. I can never forget that scene. Huge masses of shapeless rock rose up here and there among and around the houses, to the height of fifteen and twenty feet - their summits jagged, and their sides all shattered. Between them were pits and yawning fissures, as many feet in depth; while the flat surfaces of naked rock were thickly strewn with huge boulders of basalt. The narrow tortuous road by which Mūsa led us out was in places carried over chasms, and in places cut through cliffs. An ancient aqueduct ran alongside it, which, in former days, conveyed a supply of water from a neighbouring winter stream to the tanks and reservoirs from which the town gets its present name, Burāk ("the tanks"). A slow but fatiguing ride of an hour brought us out of this labyrinth of rocks, and over a torrent bed into a fine plain. We soon after passed the caravan, which had started some time before us; and, as there was no danger to be apprehended, we continued at a rapid pace southward. The dawn of morning showed us the rugged features and rocky border of the Lejah close upon our right, thickly studded with old towns and villages; while upon our left a fertile plain stretched away to the horizon. And here we observed with surprise, that there was not a trace of human habitation, except on the tops of the little conical hills which rise up at long intervals. This plain is the home of the Ishmaelite, who has always dwelt "in the presence (literally, in the face) of his brethren" (Gen. 16:12), and against whose bold incursions there never has been any effectual barrier except the munitions of rocks and the heights of hills.

We rode on. The hills of Bashan were close in front; their summits clothed with oak forests, and their sides studded with old towns. As we ascended them, the rock-fields of the Lejah were spread out on the right; and there, too, the ancient cities were thickly planted. Not less than thirty of the threescore cities of Argob were in view at one time on that day; their black houses and ruins half concealed by the black rocks amid which they are built, and their massive towers rising up here and there like the "keeps" of old Norman fortresses. How we longed to visit and explore them! But political reasons made it necessary we should, in the first place, pay our respects to one of the leading Druse chiefs. On them depended the success of our future researches. Without their protection we could not ride in safety a single mile through Haurān. I felt confident that protection would be cheerfully granted; still I thought it best not to draw bridle until we reached the town of Hiyāt, from whence, after a short pause to drink coffee with the Sheikh, who would not let us pass, we rode to the residence of Asad Amer, at Hit, where we met with a reception worthy of the hospitality of the old patriarchs.