The Giant Cities of Bashan and Syria’s Holy Places

Rev. J. L. Porter D. D.

LONDON: T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW;

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK

1877

Pages: 78 - 96V.

Salcah is situated on the south-eastern corner of Bashan. Standing on the lofty battlements of its castle, Moab

and Arabia lay before me - the former on the right, the latter on the

left, each a boundless plain reaching from the city walls to the

horizon. Behind me rose in terraced slopes the mountains of Bashan,

and over their southern declivities the eye took in a wide expanse of

its plain. Everywhere on that vast panorama, - on plain and mountain

side, in Bashan, Moab, and

Arabia, far as the eye could see and the telescope command, - were

towns and villages thickly scattered; and all deserted, though not

ruined. Many people might have thought, and a few still believe, that

there was a large amount of Eastern exaggeration in the language of

Moses when describing the conquest of this country three thousand years

ago: "We took all his cities at that time, ... threescore cities, all the region of Argob, the kingdom of Og in Bashan. All these cities were fenced with high walls, gates, and bars; beside unwalled towns a great many" (Deut. 3:4, 5). No man who has traversed Bashan,

or who has climbed the hill of Salcah, will ever again venture to bring

such a charge against the sacred historian. The walled cities, with

their ponderous gates of stone, are there now as

they were when the Israelites invaded the land. The great numbers of

unwalled towns are there too, standing testimonies to, the truth and

accuracy of Moses, and monumental protests against the poetical

interpretations of modern rationalists. There are the roads once

thronged by the teeming population; there are the fields they enclosed

and cultivated; there are the terraces they built up; there are the

vineyards and orchards they planted; all alike desolate, not poetically

or ideally, but literally "without man, and without inhabitant, and

without beast."

My friend Mr. Cyril Graham, who followed so far in my track and who was the first of European travellers to penetrate those plains beyond, which I have been trying to describe, bears his testimony to the literal fulfilment of prophecy. Some of his descriptions of what he saw are exceedingly interesting and graphic; and one is only sorry they are so very brief. Of Beth-gamul he says: "On reaching this city, I left my Arabs at one particular spot, and wandered about quite alone in the old streets of the town, entered one by one the old houses, went up stairs, visited the rooms, and, in short, made a careful examination of the whole place; but so perfect was every street, every house, every room, that I almost fancied I was in a dream, wandering alone in this city of the dead, seeing all perfect, yet not hearing a sound. I don't wish to moralize too much, but one cannot help reflecting on a people once so great and so powerful, who, living in these houses of stone within their walled cities, must have thought themselves invincible; who had their palaces and their sculptures, and who, no doubt, claimed to be the great nation, as all Eastern nations have done; and that this people should have so passed away, that for so many centuries the country they inhabited has been reckoned as a desert, until some traveller from a distant land, curious to explore these regions, finds these old towns standing alone, and telling of a race long gone by, whose history is unknown, and whose very name is matter of dispute. Yet this very state of things is predicted by Jeremiah. Concerning this very country he says these very words, - 'For the cities thereof shall be desolate, without any to dwell therein' (Jer. 48:9); and the people (Moab) 'shall be destroyed from being a people' (ver. 42). Here I think there can be no ambiguity. Visit these ancient cities, and turn to that ancient Book - no further comment is necessary."

No less than eleven of the old cities which I saw from Salcah, lying between Bozrah and Beth-gamul, were visited by Mr. Graham. Their ramparts, their houses, their streets, their gates and doors, are nearly all perfect; and yet they are "desolate, without man." This enterprising and daring traveller also made a long journey into the hitherto unexplored country east of the mountains of Bashan. There he found ancient cities, and roads, and vast numbers of inscriptions in unknown characters, but not a single inhabitant. The towns and villages east of the mountain range are all, without exception, deserted; the soil is uncultivated, and "the highways lie waste." In the whole of those vast plains, north and south, east and west, DESOLATION reigns supreme. The cities, the highways, the vineyards, the fields, are all alike silent as the grave, except during the periodical migrations of the Bedawîn, whose flocks, herds, and people eat, trample down, and waste all before them. The long predicted doom of Moab is now fulfilled: "The spoiler shall come upon every city, and no city shall escape: the valley also shall perish, and the plain shall be destroyed, as the Lord hath spoken. Give wings unto Moab, that it may flee and get away; for the cities thereof shall be desolate, without any to dwell therein." ... But why should I transcribe more? Why should I continue to compare the predictions of the Bible with the state of the country? The harmony is complete. No traveller can possibly fail to see it; and no conscientious man can fail to acknowledge it. The best, the fullest, the most instructive commentary I ever saw on the forty-eighth chapter of Jeremiah, was that inscribed by the finger of God on the panorama spread out around me as I stood on the battlements of the castle of Salcah.

It was a sad and solemn scene, - a scene of utter and terrible desolation, - the result of sin and folly; and yet I turned away from it with much reluctance. I would gladly have seen more of those old cities, and penetrated farther into that uninhabited plain. A tempting field lay there for the ecclesiastical antiquarian and the student of sacred history; but the time was not suitable for such a journey, and other duties summoned me away. *

Remounting our horses we rode along the silent streets and passed out of the deserted gates into the desolate country. After winding down the steep hill-side amid mounds of rubbish we halted in the centre of an ancient cemetery to take a last look of Salcah. The castle rose high over us on the crest of its conical hill, while the towers, walls, and terraced houses of the city extended in a serried line down the southern declivity to the plain, where they met the old gardens and vineyards. Everything seemed so complete, so habitable, so life-like, that once and again I looked and examined as the question rose in my mind, "Can this city be totally deserted?" Yes, it was so; - "without man, and without beast."

In two hours we reached Kureiyeh, and received a cordial welcome from its warlike Druse chief, Ismail el-Atrash. The town is situated in a wide valley at the south-western base of the mountains of Bashan. The ruins are of great extent, covering a space at least as large as Salcah. The houses which remain have the same general appearance as those in other towns. No large public building now exists entire; but there are traces of many; and in the streets and lanes are numerous fragments of columns and other vestiges of ancient grandeur. I copied several Greek inscriptions bearing dates of the first and second centuries in our era.

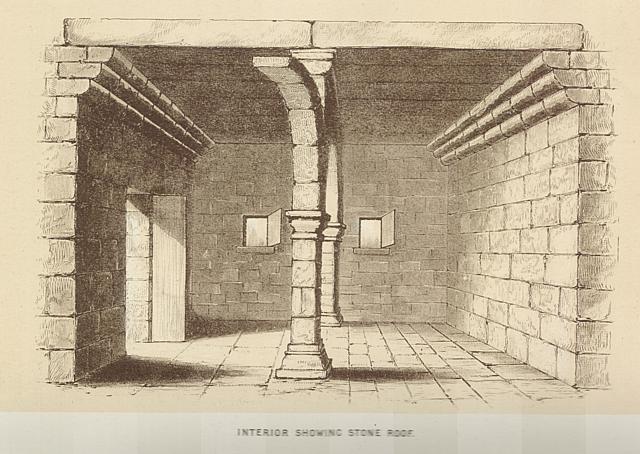

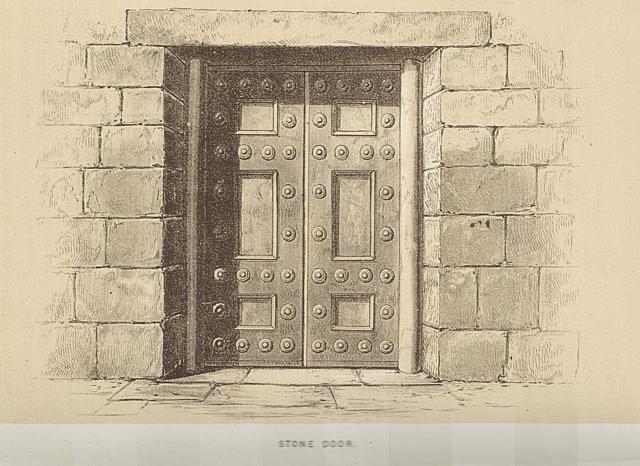

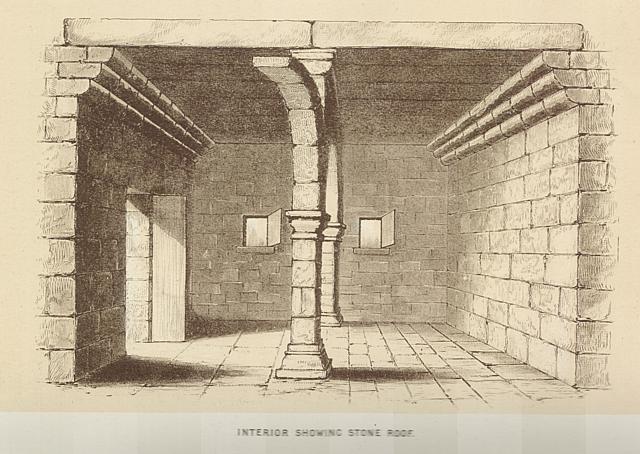

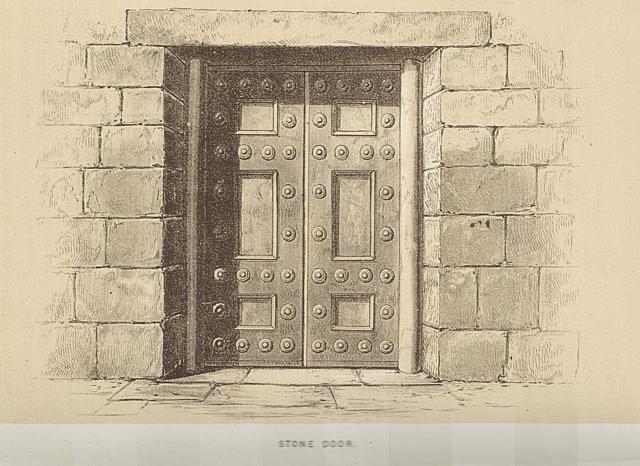

Among the cities in the plain of Moab upon which judgment is pronounced by Jeremiah, KERIOTH occurs in connection with Beth-gamul and Bozrah; and here, on the side of the plain, only five miles distant from Bozrah, stands Kureiyeh, manifestly an Arabic form of the Hebrew Kerioth. Kerioth was reckoned one of the strongholds of the plain of Moab (Jer. 48:41). Standing in the midst of wide-spread rock-fields, the passes through which could be easily defended; and encircled by massive ramparts, the remains of which are still there, - I saw, and every traveller can see, how applicable is Jeremiah’s reference, and how strong this city must, once have been. I could not but remark, too, while wandering through the streets and lanes, that the private houses bear the marks of the most remote antiquity. The few towers and fragments of temples, which inscriptions show to have been erected in the first centuries of the Christian era, are modern in comparison with the colossal walls and massive stone doors of the private houses. The simplicity of their style, their low roofs, the ponderous blocks of roughly hewn stone with which they are built, the great thickness of the walls, and the heavy slabs which form the ceilings, all point to a period far earlier than the Roman age, and probably even antecedent to the conquest of the country by the Israelites. Moses makes special mention of the strong cities of Bashan, and speaks of their high walls and gates. He tells us, too, in the same connection, that Bashan was called the land of the giants (or Rephaim, Deut. 3:13); leaving us to conclude that the cities were built by giants. Now the houses of Kerioth and other towns in Bashan appear to be just such dwellings as a race of giants would build. The walls, the roofs, but especially the ponderous gates, doors, and bars, are in every way characteristic of a period when architecture was in its infancy, when giants were masons, and when strength and security were the grand requisites. I measured a door in Kerioth: it was nine feet high, four and a half feet wide, and ten inches thick, - one solid slab of stone. I saw the folding gates of another town in the mountains still larger and heavier. Time produces little effect on such buildings as these. The heavy stone slabs of the roofs resting on the massive walls make the structure as firm as if built of solid masonry; and the black basalt used is almost as hard as iron. There can scarcely be a doubt, therefore, that these are the very cities erected and inhabited by the Rephaim, the aboriginal occupants of Bashan; and the language of Ritter appears to be true: "These buildings remain as eternal witnesses of the conquest of Bashan by Jehovah."

We have thus at Kerioth and its sister cities some of the most ancient houses of which the world can boast; and in looking at them and wandering among them, and passing night after night in them, my mind was led away back to the time, now nearly four thousand years ago, when the kings of the East warred with the Rephaim in Ashteroth-Karnaim, and with the Emim in the plain of Kiriathaim (Gen. 14:5). Some of the houses in which I slept were most probably standing at the period of that invasion. How strange to occupy houses of which giants were the architects, and a race of giants the original owners! The temples and tombs of Upper Egypt are of great interest, as the works of one of the most enlightened nations of antiquity; the palaces of Nineveh are still more interesting, as the memorials of a great city which lay buried for two thousand years; but the massive houses of Kerioth scarcely yield in interest to either. They are antiquities of another kind. In size they cannot vie with the temples of Karnac; in splendour they do not approach the palaces of Khorsabad; yet they are the memorials of a race of giant warriors that has been extinct for more than three thousand years, and of which Og, king of Bashan, was one of the last representatives; and they are, I believe, the only specimens in the world of the ordinary private dwellings of remote antiquity. The monuments designed by the genius and reared by the wealth of imperial Rome are fast mouldering to ruin in this land; temples, palaces, tombs, fortresses, are all shattered, or prostrate in the dust; but the simple, massive houses of the Rephaim are in many cases perfect as if only completed yesterday.

It is worthy of note here, as tending to prove

the truth of my statements, and to illustrate the words of the sacred

writers, that the towns of Bashan were

considered ancient even in the days of the Roman historian Ammianus

Marcellinus, who says regarding this country: "Fortresses and strong

castles have been erected by the ancient inhabitants among the retired mountains and forests. Here in the midst of numerous towns, are some great cities, such as Bostra and Gerasa, encompassed by massive walls." Mr. Graham, the only other traveller since Burckhardt, who traversed eastern Bashan, entirely agrees with me in my conclusions. "When we find," he writes, "one after another, great stone cities, walled and unwalled, with stone gates, and so crowded

together that it becomes almost a matter of wonder how all the people

could have lived in so small a place; when we see houses built of such

huge and massive stones

that no force which can be brought against them in that country could

ever batter them down; when we find rooms in these houses so large and

lofty that many of them would be considered fine rooms in a palace in

Europe; and, lastly, when we find some of these towns bearing the very

names which cities in that very country bore before the Israelites came

out of Egypt, I think we cannot help feeling the strongest conviction

that we have before us the cities of the Rephaim of which we read in the Book of Deuteronomy."

It is worthy of note here, as tending to prove

the truth of my statements, and to illustrate the words of the sacred

writers, that the towns of Bashan were

considered ancient even in the days of the Roman historian Ammianus

Marcellinus, who says regarding this country: "Fortresses and strong

castles have been erected by the ancient inhabitants among the retired mountains and forests. Here in the midst of numerous towns, are some great cities, such as Bostra and Gerasa, encompassed by massive walls." Mr. Graham, the only other traveller since Burckhardt, who traversed eastern Bashan, entirely agrees with me in my conclusions. "When we find," he writes, "one after another, great stone cities, walled and unwalled, with stone gates, and so crowded

together that it becomes almost a matter of wonder how all the people

could have lived in so small a place; when we see houses built of such

huge and massive stones

that no force which can be brought against them in that country could

ever batter them down; when we find rooms in these houses so large and

lofty that many of them would be considered fine rooms in a palace in

Europe; and, lastly, when we find some of these towns bearing the very

names which cities in that very country bore before the Israelites came

out of Egypt, I think we cannot help feeling the strongest conviction

that we have before us the cities of the Rephaim of which we read in the Book of Deuteronomy."

Kerioth is a frontier town. It is on the confines of the uninhabited plain, where the fierce Ishmaelite roams at will, "his hand against every man." The Druses of Kerioth are all armed, and they always carry their arms. With their goats on the hillside, with their yokes of oxen in the field, with their asses or camels on the road, at all hours, in all places, their rifles are slung, their swords by their side, and their pistols in their belts. Their daring chief, too, goes forth on his expeditions equipped in a helmet of steel and a coat of linked mail. In this respect also the words of prophecy are fulfilled: "Moab hath been at ease from his youth. ... Therefore, behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will send unto him wanderers, that shall cause him to wander, and shall empty his vessels, and break his bottles" (Jer. 48:12). What could be more graphic than this? The wandering Bedawîn are now the scourge of Moab; they cause the few inhabitants that remain in it to settle down amid the fastnesses of the rocks and mountains, and often to wander from city to city, in the vain hope of finding rest and security.

On one of the southern peaks of the mountain range, some two thousand feet above the vale of Kerioth, stands the town of Hebrân. Its shattered walls and houses looked exceedingly picturesque, as we wound up a deep ravine, shooting out far overhead from among the tufted foliage of the evergreen oak. Our little cavalcade was seen approaching, and ere we reached the brow of the hill the whole population had come out to meet and welcome us. The sheikh, a noble-looking young Druse, had already sent a man to bring a kid from the nearest flock to make a feast for us, and we saw him bounding away through an opening in the forest. He returned in half an hour with the kid on his shoulder. We assured the hospitable sheikh that it was impossible for us to remain. Our servants were already far away over the plain, and we had a long journey before us. He would listen to no excuse. The feast must be prepared. "My lord could not pass by his servant’s house without honouring him by eating a morsel of bread, and partaking of the kid which is being made ready. The sun is high; the day is long; rest for a time under my roof; eat and drink, and then pass on in peace." There was so much of the true spirit of patriarchal hospitality here, so much that recalled to mind scenes in the life of Abraham (Gen. 18:2), and Manoah (Judges 13:15), and other Scripture celebrities, that we found it hard to refuse. Time pressed, however, and we were reluctantly compelled to leave before the kid was served.

In the town of Hebrân are many objects of interest. The ruins of a beautiful temple, built in A.D. 155, and of several other public edifices, are strewn over the summit and rugged sides of the hill. But the simple, massive, primeval houses were to us objects of greater attraction. Many of them are perfect, and in them the modern inhabitants find ample and comfortable accommodation. The stone doors appeared even more massive than those of Kerioth; and we found the walls of the houses in some instances more than seven feet thick. Hebrân must have been one of the most ancient cities of Bashan. The view from it is magnificent. The whole country, from Kerioth to Bozrah, and from Bozrah to Salcah, was spread out before me like an embossed map; while away beyond, east, south, and west, the panorama stretched to the horizon. Two miles below me, on a projecting ridge, lay the deserted town of Afîneh, thought by some to be the ancient Ashteroth-Karnaim; about three miles eastward the grey towers of Sehweh, a large town and castle, rose up from the midst of a dense oak forest. About the same distance northward is Kufr, another town whose walls still stand, and its stone gates, about ten feet high, remain in their places. Yet the town is deserted. Truly one might repeat, in every part of Bashan, the remarkable words of Isaiah: "In the city is left desolation; and the gate is smitten with destruction" (Isa. 14:12). We observed in wandering through Hebrân, as we had done previously at Kerioth and other cities, that the large buildings, - temples, palaces, churches, and mosques, are now universally used as folds for sheep and cattle. We saw hundreds of animals in the palaces of Kerioth, and the large buildings of Hebrân were so filled with their dung that we could scarcely walk through them. This also was foreseen and foretold by the Hebrew prophets: "The defenced city shall be desolate, and left like a wilderness; there shall the calf feed, and there shall, he lie down. ... The palaces shall be forsaken, ... the forts and towers shall be for dens for ever, a joy of wild asses, a pasture of flocks" (Isa. 27:10; 32:14). And of Moab Isaiah says: "The cities of Aroer are forsaken; they shall be for flocks, which shall lie down, and none shall make them afraid" (Isa. 17:2).

From Hebrân we rode along the mountain side in a

north westerly direction, crossing a Roman road which formerly

connected the capital, Bozrah, with Kufr, Kanterah, and other large

towns among the mountains. It is now "desolate," like all the highways of Bashan,

and in places completely covered over with the branches of oak trees

and straggling brambles. In an hour we passed a group of large

villages, occupied by a few families of Druses. Here, too, we found

that the largest houses are now used as stables for camels and folds

for sheep. Continuing to descend the terraced but desolate hill-sides,

crossing several streamlets flowing through picturesque glens, and

leaving a number of deserted villages to the right and left, we at

length reached Suweideh, which we had previously visited on our way to

Bozrah.

From Hebrân we rode along the mountain side in a

north westerly direction, crossing a Roman road which formerly

connected the capital, Bozrah, with Kufr, Kanterah, and other large

towns among the mountains. It is now "desolate," like all the highways of Bashan,

and in places completely covered over with the branches of oak trees

and straggling brambles. In an hour we passed a group of large

villages, occupied by a few families of Druses. Here, too, we found

that the largest houses are now used as stables for camels and folds

for sheep. Continuing to descend the terraced but desolate hill-sides,

crossing several streamlets flowing through picturesque glens, and

leaving a number of deserted villages to the right and left, we at

length reached Suweideh, which we had previously visited on our way to

Bozrah.

I had now crossed over the southern section of the ridge, and had completed my short tour among the mountains of Bashan. It was not without feelings of regret that, after a visit so brief, I was about to turn away from this interesting region, most probably for ever. I felt glad, however, that I had been privileged to visit, even for so brief a period, a country renowned in early history, and sacred as one of the first provinces bestowed by God on his ancient people. The freshness and picturesque beauty of the scenery, the extent and grandeur of the ruins, the hearty and repeated welcomes of the people, the truly patriarchal hospitality with which I was everywhere entertained, but, above all, the convincing, overwhelming testimony afforded at every step to the minute accuracy of Scripture history, and the literal fulfilment of prophecy, filled my mind with such feelings of joy and of thankfulness as I had never before experienced. I had often read of Bashan, - how the Lord had delivered into the hands of the tribe of Manasseh, Og, its giant king, and all his people. I had observed the statement that a single province of his kingdom, Argob, contained threescore great cities, fenced with high walls, gates, and bars, besides unwalled towns a great many. I had examined my map, and had found that the whole of Bashan is not larger than an ordinary English county. I confess I was astonished; and though my faith in the Divine Record was not shaken, yet I felt that some strange statistical mystery hung over the passage, which required to be cleared up. That one city, nurtured by the commerce of a mighty empire, might grow till her people could be numbered by millions, I could well believe; that two or even three great commercial cities might spring up in favoured localities, almost side by side, I could believe too. But that sixty walled cities, besides unwalled towns a great many, should exist in a small province, at such a remote age, far from the sea, with no rivers and little commerce, appeared to be inexplicable. Inexplicable, mysterious though it appeared, it was true. On the spot, with my own eyes, I had now verified it. A list of more than one hundred ruined cities and villages, situated in these mountains alone, I had in my hands; and on the spot I had tested it, and found it accurate, though not complete. More than thirty of these I had myself visited or passed close by. Many. others I had seen in the distance. The extent of some of them I measured, and have already stated. Of their high antiquity I could not, after inspecting them, entertain a doubt; and I have explained why. Here, then, we have a venerable Record, more than three thousand years old, containing incidental descriptions, statements, and statistics, which few men would be inclined to receive on trust, which not a few are now attempting to throw aside as "glaring absurdities," and "gross exaggerations," and yet which close and thorough examination proves to be accurate in the most minute details. Here, again, are prophecies of ruin and utter desolation, pronounced and recorded when this country was in the height of its prosperity, - when its vast plains waved with corn, when its hill-sides were clothed with vineyards, when its cities and villages resounded with the busy hum of a teeming population; and now, after my survey of Bashan, if I were asked to describe the present state of plains, mountains, towns, and villages, I could not possibly select language more appropriate, more accurate, or more graphic, than the language of these very prophecies. My unalterable conviction is, that the eye of the Omniscient God alone could have foreseen a doom so terrible as that which has fallen on Moab and Bashan.

Nejrân stands just within the southern border of the Lejah. Around the city, and far as I could see westward and northward, was one vast wilderness of rocks; - here piled up in shapeless, jagged masses; there spread out in flat, rugged fields, intersected by yawning fissures and chasms. The Bible name of the province, Argob,** "the Stony," is strikingly descriptive of its physical features. I made a vigorous effort to penetrate to the interior of the Lejah, in order to visit those strange old cities which I saw in the distance from the towers of Nejrân, and of which I had heard so much; but no one would undertake to guide me, and the Druses absolutely refused to be responsible for my safety should I make the attempt. The Lejah, in fact, is the sanctuary, the great natural stronghold of the people. When fleeing from the Bedawîn, and when in rebellion against the government, they find themselves perfectly safe in its rocky recesses. They are consequently jealous of all strangers, and they will not, under any ordinary circumstances, guide travellers through its intricate and secret passes. Argob, Trachonitis, or Lejah, - for by each name has it been successively called, - has been an asylum for all malefactors and refugees ever since the time when Absalom fled to it after the murder of his brother.

Being prevented from passing through the centre of the Lejah, we turned westward to Edrei, hoping to be more fortunate in obtaining guides there. The path along which we were led was intricate, difficult, and in places even dangerous. We had often to scramble over smooth ledges of basalt, where our horses could scarcely keep their feet; and these were separated by deep fissures and chasms, here and there half filled with muddy water. A stranger would have sought in vain for the road, if road it can be called. In half an hour we reached the plain; and then continued to ride along the side of the Lejah, whose boundary resembles the rugged line of broken cliffs which gird a great part of the eastern coast of England. The Hebrew name given to it in the Bible is, most appropriate, and shows how observant the sacred writers were. The word is Chebel, signifying literally "a rope," but which describes with singular accuracy the remarkably defined boundary line which encircles the whole province like a rocky shore.

We passed in succession the deserted towns of Kirâtah, Taârah, and Duweireh, all built within the Lejah; and we saw many others on the plain to the left, and among the rocks on me right. We entered the town of Busr el-Harîry, but were received with such scowling looks and savage threats and curses by its Moslem inhabitants, that we were glad to effect our escape. We now felt that on leaving the Druse territory we had left hospitality and welcome behind, and that henceforth outbursts of Moslem fanaticism awaited us everywhere.

Under the guidance of our host, we went out in the afternoon to inspect the principal buildings of the city. A crowd of fanatical Moslems gathered round, and followed us wherever we went, trying every means to annoy and insult us. We paid no attention to them, and hoped thus to escape worse treatment. Unfortunately our hopes were vain. I was suddenly struck down by a blow of a club while copying an inscription. The crowd then rushed upon us in a body with stones, clubs, swords, and knives. I was separated from my companions, pursued by some fifty or sixty savages, all thirsting for my blood. After some hard struggles, which I cannot look back to even yet without a shudder, I succeeded in reaching our temporary home. Here I found my companions, like myself, severely wounded, and almost faint from loss of blood. Our Druse guard defended the house till midnight, and then, thanks to a merciful Providence, we made our escape from Edrei.

Edrei was the capital city of the giant Og. On the plain beside it he marshalled his forces to oppose the advancing host of the Israelites. He fell, his army was totally routed, and Edrei was taken by the conquerors (Num. 21:33; Deut. 3:1-4). Probably it did not remain long in the hands of the Israelites, for we hear no more of it in the Bible. The monuments now found in it show that it was one of the most important cities of Bashan in the time of the Romans. After the Saracenic conquest, it gradually dwindled down from a metropolitan city to a poor village; and now, though the ruins are some three miles in circuit, it does not contain more than five hundred inhabitants. How applicable are the words of Ezekiel both to the physical and to the social state of Edrei! "Thus saith the Lord, ... Behold, I, even I, will bring a sword upon you, and I will destroy your high places. ... In all your dwellingplaces the cities shall be laid waste, and the high places shall be desolate" (Ezek. 6:3, 6). "I will bring the worst of the heathen, and they shall possess their houses. ... Say unto the people of the land, Thus saith the Lord God, ... They shall eat their bread with carefulness, and drink their water with astonishment, ... because of the violence of all them that dwell therein. Every one that passeth thereby shall be astonished" (Ezek. 7:24; 12:19, &c .)

In darkness and silence we rode out of Edrei. For more than an hour we were led through rugged and intricate paths among the rocks, scarcely venturing to hope that we should ever reach the plain in safety. We did reach it, however, and with grateful hearts we rode on, guided by the stars. Before long we were again entangled in the rocky mazes of this wild region, and resolved, after several vain attempts to get out, to wait for daylight. The night wind was cold, bitterly cold; my wounds were stiff and painful; and there was no shelter from the blast save that of the shattered rocks. The spot, too, was neither safe nor pleasant for a bivouac. The mournful howl of the jackal, the sharp ringing bark of the wolf, and the savage growl of the hyena, were heard all round us. Gradually they came nearer and closer. Our poor horses quivered in every limb. We were forced to keep marching round them; for we saw, by the bright star-light and the flashing eyes, that the rocks on every side were tenanted with enemies almost as dangerous and bloodthirsty as the men of Edrei. There I knew for the first time what it was to spend a night with the wild beasts; and there I had, too, a practical and painful illustration of Isaiah’s remarkable prediction, "The wild beasts of the desert shall also, meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow," &c. (Isa. 34:14.)

Day-light came at last - not with the slow, stealing step of the West, but with the swiftness and beauty of Eastern climes. Mounting our jaded horses, we rode on between huge black stones and crags of naked rock. Climbing to the top of a little hill, we got a wide view over the Lejah. I could only compare it to the ruins of a Cyclopean city prostrate and desolate. There was not one pleasing feature. The very trees that grow amid the rocks have a blasted look. Yet, strange as it may seem, this forbidding region is thickly studded with ancient towns and villages, long ago deserted. Passing through the Lejah to the town of Khubab, we rode on northward along its border, leaving the towns of Hazkîn, Eib, Musmieh, and others, on our right. They are all deserted, and there is not a single inhabited spot east of Khubab. The rich and beautiful plain on the north of the Lejah is now desolate as the Lejah itself, and in a ride of ten miles we did not see a human being. We pursued our route to Deir Ali, and thence over the Pharpar, at Kesweh, to Damascus.

Thus ended my tour through eastern Bashan, and my explorations of its giant cities.

* Another traveller has of late traversed part of Bashan, and penetrated the desert eastward. I refer to Dr. J. G. Wetzstein, whom I had the pleasure of knowing as Prussian consul in Damascus. His little work, Reisebericht uber Haurân und die Trachonen, Berlin, 1860, is interesting and instructive. It contains the fullest account hitherto published of that remarkable region, the Safa.

** Argob appears to have been the home of the warlike tribe of Geshurites. Absalom’s mother was Maacab, daughter of Talmai, king of Geshur (2 Sam. 3:3); and when he slew his brother Amnon he fled, "and went to Geshur, and was there three years" (13:38). Probably much of Absalom’s wild and wayward spirit may be attributed to maternal training, and to the promptings of his relatives the Geshurites.

My friend Mr. Cyril Graham, who followed so far in my track and who was the first of European travellers to penetrate those plains beyond, which I have been trying to describe, bears his testimony to the literal fulfilment of prophecy. Some of his descriptions of what he saw are exceedingly interesting and graphic; and one is only sorry they are so very brief. Of Beth-gamul he says: "On reaching this city, I left my Arabs at one particular spot, and wandered about quite alone in the old streets of the town, entered one by one the old houses, went up stairs, visited the rooms, and, in short, made a careful examination of the whole place; but so perfect was every street, every house, every room, that I almost fancied I was in a dream, wandering alone in this city of the dead, seeing all perfect, yet not hearing a sound. I don't wish to moralize too much, but one cannot help reflecting on a people once so great and so powerful, who, living in these houses of stone within their walled cities, must have thought themselves invincible; who had their palaces and their sculptures, and who, no doubt, claimed to be the great nation, as all Eastern nations have done; and that this people should have so passed away, that for so many centuries the country they inhabited has been reckoned as a desert, until some traveller from a distant land, curious to explore these regions, finds these old towns standing alone, and telling of a race long gone by, whose history is unknown, and whose very name is matter of dispute. Yet this very state of things is predicted by Jeremiah. Concerning this very country he says these very words, - 'For the cities thereof shall be desolate, without any to dwell therein' (Jer. 48:9); and the people (Moab) 'shall be destroyed from being a people' (ver. 42). Here I think there can be no ambiguity. Visit these ancient cities, and turn to that ancient Book - no further comment is necessary."

No less than eleven of the old cities which I saw from Salcah, lying between Bozrah and Beth-gamul, were visited by Mr. Graham. Their ramparts, their houses, their streets, their gates and doors, are nearly all perfect; and yet they are "desolate, without man." This enterprising and daring traveller also made a long journey into the hitherto unexplored country east of the mountains of Bashan. There he found ancient cities, and roads, and vast numbers of inscriptions in unknown characters, but not a single inhabitant. The towns and villages east of the mountain range are all, without exception, deserted; the soil is uncultivated, and "the highways lie waste." In the whole of those vast plains, north and south, east and west, DESOLATION reigns supreme. The cities, the highways, the vineyards, the fields, are all alike silent as the grave, except during the periodical migrations of the Bedawîn, whose flocks, herds, and people eat, trample down, and waste all before them. The long predicted doom of Moab is now fulfilled: "The spoiler shall come upon every city, and no city shall escape: the valley also shall perish, and the plain shall be destroyed, as the Lord hath spoken. Give wings unto Moab, that it may flee and get away; for the cities thereof shall be desolate, without any to dwell therein." ... But why should I transcribe more? Why should I continue to compare the predictions of the Bible with the state of the country? The harmony is complete. No traveller can possibly fail to see it; and no conscientious man can fail to acknowledge it. The best, the fullest, the most instructive commentary I ever saw on the forty-eighth chapter of Jeremiah, was that inscribed by the finger of God on the panorama spread out around me as I stood on the battlements of the castle of Salcah.

It was a sad and solemn scene, - a scene of utter and terrible desolation, - the result of sin and folly; and yet I turned away from it with much reluctance. I would gladly have seen more of those old cities, and penetrated farther into that uninhabited plain. A tempting field lay there for the ecclesiastical antiquarian and the student of sacred history; but the time was not suitable for such a journey, and other duties summoned me away. *

Remounting our horses we rode along the silent streets and passed out of the deserted gates into the desolate country. After winding down the steep hill-side amid mounds of rubbish we halted in the centre of an ancient cemetery to take a last look of Salcah. The castle rose high over us on the crest of its conical hill, while the towers, walls, and terraced houses of the city extended in a serried line down the southern declivity to the plain, where they met the old gardens and vineyards. Everything seemed so complete, so habitable, so life-like, that once and again I looked and examined as the question rose in my mind, "Can this city be totally deserted?" Yes, it was so; - "without man, and without beast."

|

"Slumber is there, but not of rest: Here her forlorn and weary nest The famish'd hawk has found. The wild dog howls at fall of night, The serpent’s rustling coils affright The traveller on his round." |

KERIOTH.

We turned westward to Kerioth, and soon fell into the line of the ancient road, its pavement in many places perfect, though here and there torn up and swept away by mountain torrents. On our right, about two miles distant, lay Ayűn, a deserted city as large as Salcah. Kuweiris, Ain, Muneiderah, and many others were visible, - some in quiet green vales, some perched like fortresses on the sides and summits of rugged hills. The country through which our route lay was very rocky; but though now desolate, the signs of former industry are there. The loose stones have been gathered into great heaps, and little fields formed; and terraces can be traced along every hill-side from bottom to top.In two hours we reached Kureiyeh, and received a cordial welcome from its warlike Druse chief, Ismail el-Atrash. The town is situated in a wide valley at the south-western base of the mountains of Bashan. The ruins are of great extent, covering a space at least as large as Salcah. The houses which remain have the same general appearance as those in other towns. No large public building now exists entire; but there are traces of many; and in the streets and lanes are numerous fragments of columns and other vestiges of ancient grandeur. I copied several Greek inscriptions bearing dates of the first and second centuries in our era.

Among the cities in the plain of Moab upon which judgment is pronounced by Jeremiah, KERIOTH occurs in connection with Beth-gamul and Bozrah; and here, on the side of the plain, only five miles distant from Bozrah, stands Kureiyeh, manifestly an Arabic form of the Hebrew Kerioth. Kerioth was reckoned one of the strongholds of the plain of Moab (Jer. 48:41). Standing in the midst of wide-spread rock-fields, the passes through which could be easily defended; and encircled by massive ramparts, the remains of which are still there, - I saw, and every traveller can see, how applicable is Jeremiah’s reference, and how strong this city must, once have been. I could not but remark, too, while wandering through the streets and lanes, that the private houses bear the marks of the most remote antiquity. The few towers and fragments of temples, which inscriptions show to have been erected in the first centuries of the Christian era, are modern in comparison with the colossal walls and massive stone doors of the private houses. The simplicity of their style, their low roofs, the ponderous blocks of roughly hewn stone with which they are built, the great thickness of the walls, and the heavy slabs which form the ceilings, all point to a period far earlier than the Roman age, and probably even antecedent to the conquest of the country by the Israelites. Moses makes special mention of the strong cities of Bashan, and speaks of their high walls and gates. He tells us, too, in the same connection, that Bashan was called the land of the giants (or Rephaim, Deut. 3:13); leaving us to conclude that the cities were built by giants. Now the houses of Kerioth and other towns in Bashan appear to be just such dwellings as a race of giants would build. The walls, the roofs, but especially the ponderous gates, doors, and bars, are in every way characteristic of a period when architecture was in its infancy, when giants were masons, and when strength and security were the grand requisites. I measured a door in Kerioth: it was nine feet high, four and a half feet wide, and ten inches thick, - one solid slab of stone. I saw the folding gates of another town in the mountains still larger and heavier. Time produces little effect on such buildings as these. The heavy stone slabs of the roofs resting on the massive walls make the structure as firm as if built of solid masonry; and the black basalt used is almost as hard as iron. There can scarcely be a doubt, therefore, that these are the very cities erected and inhabited by the Rephaim, the aboriginal occupants of Bashan; and the language of Ritter appears to be true: "These buildings remain as eternal witnesses of the conquest of Bashan by Jehovah."

We have thus at Kerioth and its sister cities some of the most ancient houses of which the world can boast; and in looking at them and wandering among them, and passing night after night in them, my mind was led away back to the time, now nearly four thousand years ago, when the kings of the East warred with the Rephaim in Ashteroth-Karnaim, and with the Emim in the plain of Kiriathaim (Gen. 14:5). Some of the houses in which I slept were most probably standing at the period of that invasion. How strange to occupy houses of which giants were the architects, and a race of giants the original owners! The temples and tombs of Upper Egypt are of great interest, as the works of one of the most enlightened nations of antiquity; the palaces of Nineveh are still more interesting, as the memorials of a great city which lay buried for two thousand years; but the massive houses of Kerioth scarcely yield in interest to either. They are antiquities of another kind. In size they cannot vie with the temples of Karnac; in splendour they do not approach the palaces of Khorsabad; yet they are the memorials of a race of giant warriors that has been extinct for more than three thousand years, and of which Og, king of Bashan, was one of the last representatives; and they are, I believe, the only specimens in the world of the ordinary private dwellings of remote antiquity. The monuments designed by the genius and reared by the wealth of imperial Rome are fast mouldering to ruin in this land; temples, palaces, tombs, fortresses, are all shattered, or prostrate in the dust; but the simple, massive houses of the Rephaim are in many cases perfect as if only completed yesterday.

Kerioth is a frontier town. It is on the confines of the uninhabited plain, where the fierce Ishmaelite roams at will, "his hand against every man." The Druses of Kerioth are all armed, and they always carry their arms. With their goats on the hillside, with their yokes of oxen in the field, with their asses or camels on the road, at all hours, in all places, their rifles are slung, their swords by their side, and their pistols in their belts. Their daring chief, too, goes forth on his expeditions equipped in a helmet of steel and a coat of linked mail. In this respect also the words of prophecy are fulfilled: "Moab hath been at ease from his youth. ... Therefore, behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will send unto him wanderers, that shall cause him to wander, and shall empty his vessels, and break his bottles" (Jer. 48:12). What could be more graphic than this? The wandering Bedawîn are now the scourge of Moab; they cause the few inhabitants that remain in it to settle down amid the fastnesses of the rocks and mountains, and often to wander from city to city, in the vain hope of finding rest and security.

THE MOUNTAINS AND OAKS OF BASHAN.

Leaving Kerioth I turned my back on Moab’s desolate plain, and began to climb the Mountains of Bashan. Bleak and rocky at the base, they soon assume bolder outlines and exhibit grander features. Ravines cut deeply into their sides; bare cliffs shoot out from tangled jungles of dwarf ilex, woven together with brambles and creeping plants; pointed cones of basalt, strewn here and there with cinders and ashes, tower up until a wreath of snow is wound round their heads; straggling trees of the great old oaks of Bashan dot thinly the lower declivities, higher up little groves of them appear, and higher still, around the loftiest peaks, are dense forests. Our road was a goat-track, which wound along the side of a brawling mountain torrent, now scaling a dizzy crag high over it, and now diving down again till the spray of its miniature cascades dashed over our horses. For nearly two hours we rode up that wild and picturesque mountain side. We passed several small villages perched like fortresses on projecting cliffs, and we saw other larger ones in the distance; they are all deserted; and during those two hours we did not meet, nor see, nor hear a human being. We saw partridges among the rocks, and eagles sweeping in graceful circles round the mountain tops, and two or three foxes and one hyena, startled from their lairs by the sound of our horses feet; but we saw no man, no herd, no flock. The time of judgment predicted by Isaiah has surely come to this part of the land of Israel: "Behold, the Lord maketh the land empty, and maketh it waste, and turneth it upside down, and scattereth abroad the inhabitants thereof. The land shall be utterly emptied, and utterly spoiled; for the Lord hath spoken this word" (Isa. 24:1, 3).On one of the southern peaks of the mountain range, some two thousand feet above the vale of Kerioth, stands the town of Hebrân. Its shattered walls and houses looked exceedingly picturesque, as we wound up a deep ravine, shooting out far overhead from among the tufted foliage of the evergreen oak. Our little cavalcade was seen approaching, and ere we reached the brow of the hill the whole population had come out to meet and welcome us. The sheikh, a noble-looking young Druse, had already sent a man to bring a kid from the nearest flock to make a feast for us, and we saw him bounding away through an opening in the forest. He returned in half an hour with the kid on his shoulder. We assured the hospitable sheikh that it was impossible for us to remain. Our servants were already far away over the plain, and we had a long journey before us. He would listen to no excuse. The feast must be prepared. "My lord could not pass by his servant’s house without honouring him by eating a morsel of bread, and partaking of the kid which is being made ready. The sun is high; the day is long; rest for a time under my roof; eat and drink, and then pass on in peace." There was so much of the true spirit of patriarchal hospitality here, so much that recalled to mind scenes in the life of Abraham (Gen. 18:2), and Manoah (Judges 13:15), and other Scripture celebrities, that we found it hard to refuse. Time pressed, however, and we were reluctantly compelled to leave before the kid was served.

In the town of Hebrân are many objects of interest. The ruins of a beautiful temple, built in A.D. 155, and of several other public edifices, are strewn over the summit and rugged sides of the hill. But the simple, massive, primeval houses were to us objects of greater attraction. Many of them are perfect, and in them the modern inhabitants find ample and comfortable accommodation. The stone doors appeared even more massive than those of Kerioth; and we found the walls of the houses in some instances more than seven feet thick. Hebrân must have been one of the most ancient cities of Bashan. The view from it is magnificent. The whole country, from Kerioth to Bozrah, and from Bozrah to Salcah, was spread out before me like an embossed map; while away beyond, east, south, and west, the panorama stretched to the horizon. Two miles below me, on a projecting ridge, lay the deserted town of Afîneh, thought by some to be the ancient Ashteroth-Karnaim; about three miles eastward the grey towers of Sehweh, a large town and castle, rose up from the midst of a dense oak forest. About the same distance northward is Kufr, another town whose walls still stand, and its stone gates, about ten feet high, remain in their places. Yet the town is deserted. Truly one might repeat, in every part of Bashan, the remarkable words of Isaiah: "In the city is left desolation; and the gate is smitten with destruction" (Isa. 14:12). We observed in wandering through Hebrân, as we had done previously at Kerioth and other cities, that the large buildings, - temples, palaces, churches, and mosques, are now universally used as folds for sheep and cattle. We saw hundreds of animals in the palaces of Kerioth, and the large buildings of Hebrân were so filled with their dung that we could scarcely walk through them. This also was foreseen and foretold by the Hebrew prophets: "The defenced city shall be desolate, and left like a wilderness; there shall the calf feed, and there shall, he lie down. ... The palaces shall be forsaken, ... the forts and towers shall be for dens for ever, a joy of wild asses, a pasture of flocks" (Isa. 27:10; 32:14). And of Moab Isaiah says: "The cities of Aroer are forsaken; they shall be for flocks, which shall lie down, and none shall make them afraid" (Isa. 17:2).

I had now crossed over the southern section of the ridge, and had completed my short tour among the mountains of Bashan. It was not without feelings of regret that, after a visit so brief, I was about to turn away from this interesting region, most probably for ever. I felt glad, however, that I had been privileged to visit, even for so brief a period, a country renowned in early history, and sacred as one of the first provinces bestowed by God on his ancient people. The freshness and picturesque beauty of the scenery, the extent and grandeur of the ruins, the hearty and repeated welcomes of the people, the truly patriarchal hospitality with which I was everywhere entertained, but, above all, the convincing, overwhelming testimony afforded at every step to the minute accuracy of Scripture history, and the literal fulfilment of prophecy, filled my mind with such feelings of joy and of thankfulness as I had never before experienced. I had often read of Bashan, - how the Lord had delivered into the hands of the tribe of Manasseh, Og, its giant king, and all his people. I had observed the statement that a single province of his kingdom, Argob, contained threescore great cities, fenced with high walls, gates, and bars, besides unwalled towns a great many. I had examined my map, and had found that the whole of Bashan is not larger than an ordinary English county. I confess I was astonished; and though my faith in the Divine Record was not shaken, yet I felt that some strange statistical mystery hung over the passage, which required to be cleared up. That one city, nurtured by the commerce of a mighty empire, might grow till her people could be numbered by millions, I could well believe; that two or even three great commercial cities might spring up in favoured localities, almost side by side, I could believe too. But that sixty walled cities, besides unwalled towns a great many, should exist in a small province, at such a remote age, far from the sea, with no rivers and little commerce, appeared to be inexplicable. Inexplicable, mysterious though it appeared, it was true. On the spot, with my own eyes, I had now verified it. A list of more than one hundred ruined cities and villages, situated in these mountains alone, I had in my hands; and on the spot I had tested it, and found it accurate, though not complete. More than thirty of these I had myself visited or passed close by. Many. others I had seen in the distance. The extent of some of them I measured, and have already stated. Of their high antiquity I could not, after inspecting them, entertain a doubt; and I have explained why. Here, then, we have a venerable Record, more than three thousand years old, containing incidental descriptions, statements, and statistics, which few men would be inclined to receive on trust, which not a few are now attempting to throw aside as "glaring absurdities," and "gross exaggerations," and yet which close and thorough examination proves to be accurate in the most minute details. Here, again, are prophecies of ruin and utter desolation, pronounced and recorded when this country was in the height of its prosperity, - when its vast plains waved with corn, when its hill-sides were clothed with vineyards, when its cities and villages resounded with the busy hum of a teeming population; and now, after my survey of Bashan, if I were asked to describe the present state of plains, mountains, towns, and villages, I could not possibly select language more appropriate, more accurate, or more graphic, than the language of these very prophecies. My unalterable conviction is, that the eye of the Omniscient God alone could have foreseen a doom so terrible as that which has fallen on Moab and Bashan.

ARGOB.

From Suweideh I rode north-west across the noble plain of Bashan, passing in succession the villages of Welgha, Rimeh, Mezraah, and Sijn, and seeing many others away on the right and left. Most of them contain a few families of Druses; but not one-tenth of the habitable houses in them are inhabited. These houses are in every respect similar to those in the mountains. I was now approaching the remarkable province of Lejah, the ancient Argob, properly so called. A four hours' ride brought me to Nejrân, whose massive black walls and heavy square towers rise up lonely and desolate from the midst of a wilderness of rocks. The town has still a comparatively large population; that is, there are probably a hundred families settled in the old houses, which cover a space more than two miles in circumference. It contains a number of public buildings, the largest of which is a church, dedicated, as a Greek inscription informs us, in the year A.D. 564.Nejrân stands just within the southern border of the Lejah. Around the city, and far as I could see westward and northward, was one vast wilderness of rocks; - here piled up in shapeless, jagged masses; there spread out in flat, rugged fields, intersected by yawning fissures and chasms. The Bible name of the province, Argob,** "the Stony," is strikingly descriptive of its physical features. I made a vigorous effort to penetrate to the interior of the Lejah, in order to visit those strange old cities which I saw in the distance from the towers of Nejrân, and of which I had heard so much; but no one would undertake to guide me, and the Druses absolutely refused to be responsible for my safety should I make the attempt. The Lejah, in fact, is the sanctuary, the great natural stronghold of the people. When fleeing from the Bedawîn, and when in rebellion against the government, they find themselves perfectly safe in its rocky recesses. They are consequently jealous of all strangers, and they will not, under any ordinary circumstances, guide travellers through its intricate and secret passes. Argob, Trachonitis, or Lejah, - for by each name has it been successively called, - has been an asylum for all malefactors and refugees ever since the time when Absalom fled to it after the murder of his brother.

Being prevented from passing through the centre of the Lejah, we turned westward to Edrei, hoping to be more fortunate in obtaining guides there. The path along which we were led was intricate, difficult, and in places even dangerous. We had often to scramble over smooth ledges of basalt, where our horses could scarcely keep their feet; and these were separated by deep fissures and chasms, here and there half filled with muddy water. A stranger would have sought in vain for the road, if road it can be called. In half an hour we reached the plain; and then continued to ride along the side of the Lejah, whose boundary resembles the rugged line of broken cliffs which gird a great part of the eastern coast of England. The Hebrew name given to it in the Bible is, most appropriate, and shows how observant the sacred writers were. The word is Chebel, signifying literally "a rope," but which describes with singular accuracy the remarkably defined boundary line which encircles the whole province like a rocky shore.

We passed in succession the deserted towns of Kirâtah, Taârah, and Duweireh, all built within the Lejah; and we saw many others on the plain to the left, and among the rocks on me right. We entered the town of Busr el-Harîry, but were received with such scowling looks and savage threats and curses by its Moslem inhabitants, that we were glad to effect our escape. We now felt that on leaving the Druse territory we had left hospitality and welcome behind, and that henceforth outbursts of Moslem fanaticism awaited us everywhere.

EDREI.

Soon after leaving Busr, the towers of Edrei came in sight, exploding along the summit of a projecting ledge of rocks in front, and running some distance into the interior of the Lejah an the right. Crossing a deep ravine, and ascending the rugged ridge of rocks by a winding path like a goat track, we came suddenly on the ruins of this ancient city. The situation is most remarkable: - without a single spring of living water; without river or stream; without access, except over rocks and through defiles all but impassable; without tree or garden. In selecting the site, everything seems to have been sacrificed to security and strength. Shortly after my arrival I went up to the terraced roof of a house, to obtain a general view of the ruins. Their aspect was far from inviting; it was wild and savage in the extreme. The huge masses of shattered masonry could scarcely be distinguished from the rocks that encircle them; and all, ruins and rocks alike, are black, as if scathed by lightning. I saw several square towers, and remains of temples, churches, and mosques. The private houses are low, massive, gloomy, and manifestly of the highest antiquity. The inhabitants are chiefly Moslems; but as there is a little Christian community, we selected the house of their sheikh as our temporary residence.Under the guidance of our host, we went out in the afternoon to inspect the principal buildings of the city. A crowd of fanatical Moslems gathered round, and followed us wherever we went, trying every means to annoy and insult us. We paid no attention to them, and hoped thus to escape worse treatment. Unfortunately our hopes were vain. I was suddenly struck down by a blow of a club while copying an inscription. The crowd then rushed upon us in a body with stones, clubs, swords, and knives. I was separated from my companions, pursued by some fifty or sixty savages, all thirsting for my blood. After some hard struggles, which I cannot look back to even yet without a shudder, I succeeded in reaching our temporary home. Here I found my companions, like myself, severely wounded, and almost faint from loss of blood. Our Druse guard defended the house till midnight, and then, thanks to a merciful Providence, we made our escape from Edrei.

Edrei was the capital city of the giant Og. On the plain beside it he marshalled his forces to oppose the advancing host of the Israelites. He fell, his army was totally routed, and Edrei was taken by the conquerors (Num. 21:33; Deut. 3:1-4). Probably it did not remain long in the hands of the Israelites, for we hear no more of it in the Bible. The monuments now found in it show that it was one of the most important cities of Bashan in the time of the Romans. After the Saracenic conquest, it gradually dwindled down from a metropolitan city to a poor village; and now, though the ruins are some three miles in circuit, it does not contain more than five hundred inhabitants. How applicable are the words of Ezekiel both to the physical and to the social state of Edrei! "Thus saith the Lord, ... Behold, I, even I, will bring a sword upon you, and I will destroy your high places. ... In all your dwellingplaces the cities shall be laid waste, and the high places shall be desolate" (Ezek. 6:3, 6). "I will bring the worst of the heathen, and they shall possess their houses. ... Say unto the people of the land, Thus saith the Lord God, ... They shall eat their bread with carefulness, and drink their water with astonishment, ... because of the violence of all them that dwell therein. Every one that passeth thereby shall be astonished" (Ezek. 7:24; 12:19, &c .)

In darkness and silence we rode out of Edrei. For more than an hour we were led through rugged and intricate paths among the rocks, scarcely venturing to hope that we should ever reach the plain in safety. We did reach it, however, and with grateful hearts we rode on, guided by the stars. Before long we were again entangled in the rocky mazes of this wild region, and resolved, after several vain attempts to get out, to wait for daylight. The night wind was cold, bitterly cold; my wounds were stiff and painful; and there was no shelter from the blast save that of the shattered rocks. The spot, too, was neither safe nor pleasant for a bivouac. The mournful howl of the jackal, the sharp ringing bark of the wolf, and the savage growl of the hyena, were heard all round us. Gradually they came nearer and closer. Our poor horses quivered in every limb. We were forced to keep marching round them; for we saw, by the bright star-light and the flashing eyes, that the rocks on every side were tenanted with enemies almost as dangerous and bloodthirsty as the men of Edrei. There I knew for the first time what it was to spend a night with the wild beasts; and there I had, too, a practical and painful illustration of Isaiah’s remarkable prediction, "The wild beasts of the desert shall also, meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow," &c. (Isa. 34:14.)

Day-light came at last - not with the slow, stealing step of the West, but with the swiftness and beauty of Eastern climes. Mounting our jaded horses, we rode on between huge black stones and crags of naked rock. Climbing to the top of a little hill, we got a wide view over the Lejah. I could only compare it to the ruins of a Cyclopean city prostrate and desolate. There was not one pleasing feature. The very trees that grow amid the rocks have a blasted look. Yet, strange as it may seem, this forbidding region is thickly studded with ancient towns and villages, long ago deserted. Passing through the Lejah to the town of Khubab, we rode on northward along its border, leaving the towns of Hazkîn, Eib, Musmieh, and others, on our right. They are all deserted, and there is not a single inhabited spot east of Khubab. The rich and beautiful plain on the north of the Lejah is now desolate as the Lejah itself, and in a ride of ten miles we did not see a human being. We pursued our route to Deir Ali, and thence over the Pharpar, at Kesweh, to Damascus.

Thus ended my tour through eastern Bashan, and my explorations of its giant cities.

* Another traveller has of late traversed part of Bashan, and penetrated the desert eastward. I refer to Dr. J. G. Wetzstein, whom I had the pleasure of knowing as Prussian consul in Damascus. His little work, Reisebericht uber Haurân und die Trachonen, Berlin, 1860, is interesting and instructive. It contains the fullest account hitherto published of that remarkable region, the Safa.

** Argob appears to have been the home of the warlike tribe of Geshurites. Absalom’s mother was Maacab, daughter of Talmai, king of Geshur (2 Sam. 3:3); and when he slew his brother Amnon he fled, "and went to Geshur, and was there three years" (13:38). Probably much of Absalom’s wild and wayward spirit may be attributed to maternal training, and to the promptings of his relatives the Geshurites.

Giant Cities of Bashan - Index