MASSACRE CANYON in the Black Range -- In 1976 Jim Grider and I took several Boy Scouts from T or C on a camping trip in the Black Range. While on that trip we also located a number of burial sites of U.S. Cavalry troopers, Indian Scouts and at least one civilian killed in an all-day firefight with Victorio and his men in 1879. I had first been to the location in 1973.

Last Saturday I was able to return to that battle site through the kindness and assistance of the ranch family who owns the property that the grave sites are on, adjacent to forest lands administered by the U.S. Forest Service. Most, but not all, of the actual battle site is on public forest lands, but extremely difficult to reach unless you are on horseback or willing and able to hike 10 miles and climb up and over a 7800 foot peak in and out of the area.

On September 18, 1879, Navajo scouts attached to Company B and Company E of the U.S. Ninth Cavalry, tracked Victorio, War Chief of the Warm Springs Apaches and about 60 warriors, up Las Animas Creek. Troopers from Companies B, C, E, and G were in pursuit of Victorio after he had left the reservation at Fort Stanton, refusing to be transported back to Arizona. His stated desire was to remain at Ojo Caliente, which the federal government refused. Ojo Caliente, on the fringes of the Black Range, was the historical home of the Warm Springs Apaches. And Victorio's people, after having been promised that they could remain at Ojo Caliente, were forced to move to Arizona to live among other Apaches who were their enemies, and on a reservation on the desert best known for its pestilence and the death of hundreds of Apache men, women and children. Victorio did not stay there long. His people came from the high country and that fact was totally ignored by the government after giving him the promise that he and his people could remain in their home lands if they turned themselves in and became reservation residents.

Victorio eventually turned himself in at Fort Stanton, again asking to return to Ojo Caliente. That request was again refused and he was told that he and his people would be returned to Arizona. It was the string of broken promises that lead up to the Massacre.

After leaving Stanton and the Mescalero Reservation on September 3, 1879, Victorio attacked near Camp Ojo Caliente, capturing eighteen mules, fifty cavalry horses, and killing five Black troopers and three civilians guarding the animals.

After that attack the cavalry made an all-out effort to capture Victorio and Col. Edward Hatch put four companies of the Ninth Cavalry in the field to find Victorio and either capture him or kill him. They did neither.

And what became known as the "Victorio War" began.

In the past Victorio had encountered troopers from the Ninth Cavalry and each and every time was victorious in the field. Why anyone in command of the four companies that met him head on on Las Animas Creek could possibly think that this time is would be different is still an unanswered question today.

Victorio was perhaps the finest guerilla fighter ever known and most certainly, one of the finest the United States Army had ever had occasion to meet in the field, and he was an old man.

Throughout the so-called "Victorio War" the chief never had more than one hundred warriors, and usually less than 50. The Army had more than one thousand men in the field chasing him.

On the morning of September 18, 1879, Company B, under command of Lt. Byron Dawson, and Company E, under command of Capt. Ambrose Hooker, following their Navajo scouts, rode up Las Animas Creek and into the history books. The cavalry units were assigned part-time to Camp Ojo Caliente.

Their intent apparently was to surprise Victorio. What they apparently did not know was that they were riding not only into a trap but approaching one of the Warm Springs Apaches' main mountaintop camp sites, today called Vic's Peak and Victoria Park. The incorrect use of the name Victoria instead of Victorio has never been corrected.

The troopers fell under a heavy concentration of rifle and arrow fire at the junction of Las Animas Creek (and Canyon) and a side canyon now known as Massacre Canyon.

The troopers were caught in a three-way trap with Victorio's men firing from the heights of Las Animas and the side canyon, with nothing to hide behind but boulders, a few rock shelves and trees. Victorio had command of all the heights surrounding the two companies and there was no way the troopers could approach the Apaches without being hit.

All the men in both companies, now dismounted, were pinned down and most certainly would have been wiped out. However, the gunfire was heard echoing and re-echoing down the canyon by men with Companies C and G and they rushed to the battle scene only to be pinned down as well.

All four companies withdrew at nightfall.

There are conflicting reports about just how many troopers were killed and wounded in that battle. One official report says five troopers killed, one wounded, thirty-six horses killed, six wounded, three Navajo scouts killed and one civilian killed. Another report places the count at six troopers killed, the horse count is the same, but two Navajo scouts killed and one civilian. Yet three Medals of Honor were awarded to three different men who saved wounded troopers, therefore I do not believe any of the official reports are very accurate.

None of these figures account for 32 or more graves located near the battle site.

Official Army estimates place Victorio's strength at 120 men and has to be grossly inflated. Correct figures would be more like 50 to 60.

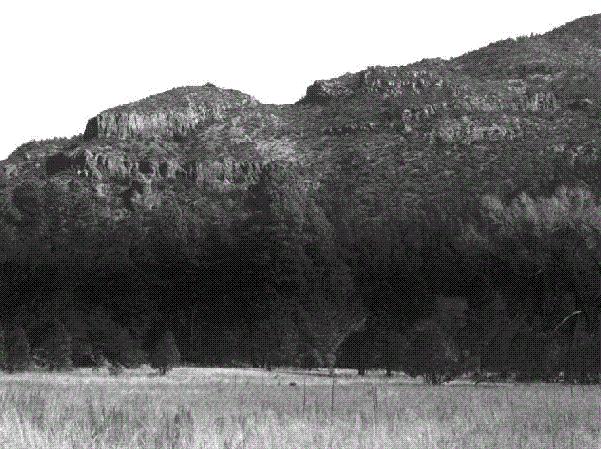

Victorio chose his ambush site with care. It was on his home turf and at a location which the Army found, to their chagrin, to be impossible to overrun or for them to defend themselves. the Animas drops off the Continental Divide in the Black Range eastward to the Rio Grande and is surrounded by high cliffs at elevations running from seven to nine thousand feet, with heavy timber.

The canyon walls in Las Animas and the surrounding side canyons are rugged, some pinnacled, a maze of side canyons with numerous caves and overhangs, all highly defensible by those waiting in ambush. Victorio used his knowledge of the terrain to the fullest. Victorio and his men left the immediate area the next day and shortly thereafter met head on with some of the same troopers again on Las Palomas Creek, but that is another story.

Several days later Lt. Dawson escorted Major Albert Morrow, commander of all military operations in southern New Mexico, over the battle site and Morrow reported that it took him 120 minutes to climb to the Apache camp and under fire it would have been an "absolute impossibility for any number of men to take the position by storm."

Late in the battle Lt. Matthias Day carried a wounded trooper to safety after refusing to leave the battle field and his wounded and in so doing was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. For heroism in the same battle Sgt. John Denny was also awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for saving a wounded private by the name of Freeland. Lt. Robert Emmet was also awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions that day.

There is no known record of how many men Victorio may have lost, if any, but walking over the battle site can only make one wonder how in the world anyone would be dumb enough to possibly think that they could dislodge Victorio or anyone else from their positions.

With the able assistance of Brent Bason the grave sites were found on a flat nearby a homestead cabin maintained as a line cabin for the Bason Ranch. We also walked over a portion of the battle site and found one large boulder that appeared to have been hit by bullets. From the angle and location of the boulder, the rounds striking the boulder had to have come from a higher elevation, therefore it is assumed that they were rounds fired by Victorio's men.

Because Las Animas Creek is mostly on patented lands, originally homesteads which have been acquired by neighboring ranches through the years, the area is comparatively untouched by "modern" civilization. And the area of the battle site on forest lands is so difficult to reach that generally things are as they were in 1879, although now there appears to be a lot of underbrush and smaller trees that may not have been there at the time. Hopefully being untouched will never change. The public has a habit of ruining anything and everything they come in contact with. The whole region has been used for cattle ranching for over 100 years and it is obvious from the look of the range, the abundance of grass and forage and the cattle, that the land has been well-managed and taken care of for a very long time by those ranching and raising cattle in the region. And bison are also grazing on some portions of Las Animas as well. It is a portion of our State that if at all possible, should remain as it is and in private hands so that it is never ruined or exploited as so many places have been.

Standing on a portion of the battle site, in the silence of the mountains, it was not difficult to imagine how that day in September 1879 must have gone for the cavalry, they did not have a prayer.

In the 1930s members of the Civilian Conservation Corps replaced wooden crosses that had been erected at the grave site but those crosses long ago fell down, were dislodged or simply disintegrated with time.

And bear, looking for bugs, have rolled the stones covering the graves over and scattered many of the rocks, making it difficult to identify each individual grave site today.

Jimmy Bason, owner of the land which the graves are located on, said that he intends to secure the site and perhaps re-mark each grave that he identified, and we will sure pitch in and help him do that financially and work-wise. Jim Paxton, District Ranger for the Black Range District, had indicated that the Forest Service would be interested in doing the same thing.

Why there are apparently thirty-two or more graves at the site instead of the eight or nine indicated in military reports is unknown. But the most accepted theory is that more men were lost in the battle than the Army was prepared to admit.

The graves lay in two rows separated by a 20 to 30 foot span, on level ground above Las Animas Creek. There are also at least three more graves apart from the two rows mentioned above and it has been suggested that those three may be the burial sites of the Navajo scouts.

The beauty and silence of the spot today, the last resting place for men, mostly Black Buffalo Soldiers, who fought against Victorio, stands as a reminder of the foolishness and dishonesty of some of those in our government of the time. The battle never had to happen, nor many of the others of the Apache Wars that took so many lives on both sides and all the civilians caught in the middle. All our government had to do was keep its word and maintain the treaties and promises made by government officials to the Apaches. That was not done..