|

By

Ted A. Morris, Lt. Col., USAF, Retired

Go

to the Photo

Album

for this Story! Its picture-heavy, and may

take a while to load, but I think you'll like it!

Today, Dhahran is quite a modern Arabian center with a first class airfield, but in 1950-1951 it was a small, almost Beau Gueste outpost, with Quonset huts and tents, a few stone buildings and a couple of runways instead of a legionnaire fortress. The 1414th Air Base Group, MATS, operated Dhahran Air Field and during most of my 15 month tour, Flight “D” was the only tactical unit assigned. Flight “D” was only half the normal size of a Rescue Flight. We had two lifeboat-carrying SB-17G aircraft and one H-5H helicopter mounted on floats. The SB-17Gs were replaced in the summer of 1950 with the first two SA-16A aircraft assigned to an overseas unit. Another vital Flight 'D' mission wag the operation of a Land Rescue component with two 6x6, 4-ton 'Diamond T' trucks and a 4x4 Dodge ambulance specialty adapted for desert travel. There were 11 officers and 30 enlisted personnel assigned to Flight -D-. There were only 225 U.S. military personnel assigned to the base.

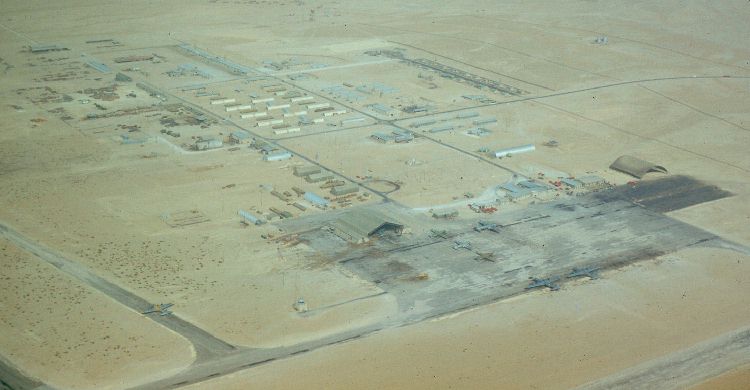

Dhahran Air Field, Saudi Arabia, 1950. Located just inland of the Persion Gulf. In 1950, Dhahran was the easternmost major US Air Force installation. On the parking ramp sit two WB-29, three C-47, and one C-54 aircraft. A Flight 'D' SB-17G is on the taxiway to the left. Quonset huts, tents, stone and tin buildings made up the bulk of the facilities. The hangar in the center of the photo lacked doors, pruducing a venturi effect during sand storms, making it virtually impossible to use. Saudi Arabia, in 1950, was a nation ruled by an absolute monarch, King Ibn Saud. Through force of arms and intermarriage, King Saud brought together the numerous fiercely independent Arab tribes into the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The main sources of national income were oil revenues from the just-beginning Arabian American Oil Company (ARAMCO), and a tax on every Moslem making their once in a lifetime pilgrimage to Islam's holy city of Mecca. Anyone not a Mohammedan was considered an infidel and King Saud kept tight control on the number permitted in his nation, especially those who did not contribute to the national wealth. There were lots of ARAMCO employees producing money for the country, but the U.S. Air Force was not, hence the tight limit of 225 military at Dhahran. Personnel changes at Dhahran were permitted only twice yearly, in January and July, except for emergencies and these had to be approved by the King's representative. As replacements, we arrived in January 1950 on a Tuesday MATS Atlantic Division C-54 from Westover AFB, Massachusetts, via Argentina NAS, Newfoundland; Lages AB, Azores; Port Lyouty NAS, Morocco; Wheelus AB, Tripoli; and Nicosia RAFB, Cyprus. Because of the tight Saudi control on personnel numbers, the men we were replacing left on the same plane the next morning for the return flight. This meant a very short introduction to one's duties! The normal tour was 12 months. Trans World Airlines, affectionately called 'Teenie Weenie Air' by all of us, operated a Constellation round-trip flight three times a week from New York to Bombay, India. These TWA flights delivered our biggest morale booster -Air Mail; we usually received a letter the same week it wag mailed stateside. Regular surface mail came via a MATS flight and usually took four weeks for delivery. The next big morale booster was our dining hall. We probably had the best food and food service of any military establishment during those years. The cooks were Italian chefs, former colonists of Mussolini's Eritrea and Somaliland provinces. In the mess, six men sat to a table set with table cloths and china while Italian waiters served the meals. Fresh vegetables, fruits and meat came from Asmara, Eritrea, on the 1414th Base Flight C-54. The cooks and waiters provided outstanding service to us enlisted men. At the close of a satisfactory three-year contract Italian employees were provided return passage to Italy; with a five-year contract they were allowed to immigrate to the U.S. This provided tremendous incentive to do good job and complete the contracts. With the exceptions of the air mail and excellent food, everything else was close to being the pits. We lived in Quonset huts and had to walk anywhere we needed to go, although the base was only several hundred acres in size. The base theater used 16 mm films with one projector and everyone was admitted--Saudi Army Arabs, Italians and U.S personnel. In those days, many of the Saudis were quite literally 'Camel Jockeys,' and with their lack of bathing facilities the odor in the theater sometimes got pretty ripe. We sat on wooden benches or the floor, but the movies were free. Initially there had been an Officers' Club and an NCO Club, but following a fight between a sergeant and the Saudi Army colonel in charge of the Arabian troops the clubs were closed and the base became 'dry.' Some troops suffered some severe withdrawal problems. The 'D' Flight three-vehicle Land Rescue Team was an important part of the overall operation, and equipped for desert travel, rescue and recovery. The 4x4 Dodge ambulance was fitted with C-47 main gear tires and the two 6x6 4-ton Diamond T Trucks were equipped with ARAMCO designed low pressure tires to enable us to travel across the desert sands. One of the 6x6 trucks was painted red and carried 800-gallons of gas, 50-gallons of oil, spare parts, tools and maintenance equipment. The other 6x6 Diamond T was painted white and carried 500-gallons of drinking water, rations, a PE-2 electric generator, and VHF and LF radio sets. Team personnel were volunteers and performed as drivers, mechanics, radio operators, ‘wreck painters’, and 'specimen collectors.' One of the missions for the Land Rescue Team at Dhahran wag collecting information for an Air Force pamphlet on desert survival. Desert survival training trips were conducted throughout Saudi Arabia. I participated in three--a 15 day trip in February 1950 from Dhahran north of the Kuwaiti border, a 21-day trip in April 1950 to the central Harasian Plateau region, and a 31-day trip in June 1950 into the southern 'Empty Quarter,' the desolate Rub al Khali Desert. We practiced rescue operations by searching for and locating old aircraft wrecks, painting them yellow to identify them for future reference. A French Navy F4U, an RAF Anson, and a U.S. B-29 were among the old wrecks located, identified and painted. We also collected anything that crawled, slithered, walked, ran or otherwise moved in the desert. We returned these specimens to the U.S. for evaluation of their benefit or hazard to survival in the desert. Spiders, snakes, lizards, foxes, and gazelles were among some of the more identifiable desert life we collected. Travel by truck over rugged open country was quite an operation. Getting stuck was common and varied from breaking through a hard baked crust into a quagmire that was like wet cement, and which hardened just as readily, to sinking up to the truck bed in soft sand while crossing dunes. Flat tires occurred often and each vehicle carried two ready spare tires. Tire changing was a major job, particularly once both ready spares had been used. It was then necessary to disassemble, patch and reassemble the tires. This was a mean, time-consuming operation, guaranteed to wear several men down in the desert's arid heat. Daytime temperatures often ranged over the 100-degree mark and in the night we felt as though we would freeze. The wind always seemed to blow, often developing into fierce desert sand storms called 'schmalls.' These brought everything to a halt while we tried to survive the onslaught of stinging, blinding sand. It is ironic that with all that desert sand in Arabia, it was necessary to import construction sand to make cement since desert sand crystals are round and will not adhere to one another. On our June, 1950 trip to the Rub al Khali we stopped at the oasis of Whahat Jabrin, 200 miles to the south of Dhahran, where we discovered the remains of several adobe style buildings. A very old Arab there explained through our ever-present King's representative, Saudi Army Liaison Officer Lt. Hakim, that the population of the oasis had been decimated by malaria nearly 100 years earlier. Only his family lived there at the time of our visit, and he was the King's official caretaker of the oasis. After verifying with Lt. Hakim that we had the King's authorization to be traveling through this area of responsibility, we traded several pounds of coffee and canned goods for camel rides and a visit to his 10 by 10 feet home. It was constructed of palm logs, covered by palm fronds and inhabited by the Arab's large family and innumerable bugs. He made tea for us in a very ornate copper and brass teapot and served it scalding hot in small glasses. He was going to kill and cook one of his goats for a feast; however, we were able to convince him to be our guest and eat some of our food. Hospitality was not our only reason as none of us wanted to become a victim of whatever internal parasites might infect his goat. Later, the old Arab visited our campsite near one of the oasis wells. We had built two fires, one for cooking and one to boil some well water for later analysis to see if boiling would remove flukes and other parasites. We also used some hot water for make-shift bucket showers. The caretaker informed us we had built the fires on top of year's accumulation of dead palm vegetation and that the fire would burn downwards many feet and, spreading underground, could get the entire 50-acre oasis aflame. He made us dig down more than six-feet to extinguish the fires. Lt. Hakim later informed us that had we ignored the caretakers' directions and left the Old Arab to be responsible for our carelessness, the King would surely have executed the old fellow, and probably Lt. Hakim as well, for failure to protect royal property.

Flight 'D' Land Rescue Team vehicles crawling up an erk in the Rub al Khali desert. The Rub al Khali desert is the very forbidding 'Empty Quarter' of the southern Arabian peninsula. It is the world's fifth largest desert, covering over 300,000 square miles. A major terrain feature of this desert consists of parallel rows of sand dunes running northeast to southwest. These dunes, called erks, are 300 to 500 feet high and about 1500 yards apart. As our expedition was traveling north to south, we had to cross many of these erks. In order to get a truck up and over these dunes, it was necessary to place the trucks in six-wheel drive, low gear, and attempt to creep up the dune at a shallow angle. At times it required more than a mile of travel to crawl over these sandy obstacles. Many times it was necessary to drive the lighter weight ambulance up the dune, run the Power Take Off winch cable out from the large truck to the ambulance, which acted as an anchor, and then, using 6-wheel drive, low gear range and take up on the PTO winch, more or less winch the truck up and over the erk. These operations required many hours and much manpower, making the distance we were able to travel short on some days. We camped and explored in the Rub al Khali for three days in mid-June at about 19-degrees north latitude which was close to the undefined border of South Yemen and Saudi Arabia. The air temperature exceeded 120-degrees (the limit of our gauge), humidity measured about one percent and the temperature o f the surface sand was over 100-degrees. Even for our Rescue Team, just surviving proved to be a major effort. These was no natural life, no moisture, no shade, and no protection from the fierce wind-driven sand. Our best recommendation to the survival pamphlet authors was for aircrews to never become stranded in the 'Empty Quarter.' During the return from our survival information gathering trip into the Rub al Khali, we were refueled and resupplied by air in a large gravel-plain area called Abu-Bahr on the northern edge of the desert. Selecting a large, fairly level area, we used the large trucks to mark-off a landing zone several miles long by driving back and forth to indicate the actual landing strip. An SB-17G with two three-hundred gallon bomb bay tanks, one filled with truck gas and the other with drinking water, landed and provided replenishment to our very dehydrated desert traveling party. On other resupply flights, mail, food and spare parts, including spare tires, were dropped by parachute from the SB-170. To enable the aircrew to recover the parachutes and outgoing mail when a landing was not possible, a rudimentary rig consisting of a grappling hook on the end of a nylon line was lowered from the SB-17G. On the ground a nylon line and container were strung between the two large trucks. The SB-17G flew between the trucks, quite low to the ground and snatched the pick-up line. The aircrew then hauled the container hand over hand into the aircraft's aft entrance door.

The hard part of our resupply. SB-17G 485746 retrieves the parachutes, outgoing mail, and truck parts in need of major repair. In the fierce desert heat this was a very hazardous task for the aircrew. Flight 'D' conducted several air-sea rescues during my tour of duty. On a Tuesday night in June 1950 an Air France DC-4 attempted to land during a severe sand storm on the nearby island of Bahrain. Unfortunately the pilot lined up, not with the runway, but with a nearby ship pier which extended out into the Persian Gulf. As a result, he crashed into the Gulf. Captain Guy Moshier and aircrew member, SSgt Lonnie Davis immediately launched our H-5H float equipped helicopter into the storm and flew to assist in rescue efforts. Landing in the Gulf at night and taxiing about in the debris of the wreck, Sergeant Davis pulled a lone survivor into the helicopter. The storm continued unabated through Wednesday and Thursday. Capt. Moshier and SSgt Davis continued to search the shark infested waters for bodies, On Thursday night while the storm continued to blanket the area with blinding, stinging sand, a second Air France DC-4 made the exact same mistake, crashing into the Persian Gulf. The helicopter crew members managed to rescue three pitiful survivors from this crash. Four survivors and 97 dead was the horrible tally from these two crashes in 48 hours. Suddenly in June 1950 the U.S. was again at war, this time in Korea. The only armament available to the U.S. troops at Dhahran at the time consisted of .22 cal/410 gauge over-and-under survival rifles packed in Flight 'D' survival packs. There was a frenzy of activity digging trenches and gun emplacements, and making plans to deny the Air Field to anyone that might want it while we awaited a shipment of defensive arms and ammunition. Everyone was assigned a task in defending the base. It was a tense time to our handful of U.S. troops located on the backside of the world. Then, from out of the blue, it was decided to equip Flight 'D' with the brand new SA-16A 'Albatross' amphibian aircraft just entering the Air Force inventory. These were the first SA-16As assigned outside the CONUS. Four pilots, three crew chiefs/flight mechanics (Nilo P. Pollo, Loyd Cameron, and myself), and two radio operators were quickly sent to MacDill AFB, Florida, for two weeks transition training and then to the Grumman Aircraft Factory in New York to pick up the 21st and 22nd SA-16A aircraft delivered to the Air Force. These were 49-074, and my aircraft, 49-075. Behaving as true crew chiefs assigned to a god-forsaken backwater, TSgt Nilo P. Pollo and I scrounged every available spare part not tied down at the Grumman plant in order to get our aircraft to Dhahran and. keep them flying once we arrived. Our return to Dhahran was via Westover AFB, Massachusetts; Goose Bay AB, Labrador; BWI AB, Greenland; Keflavik, Iceland; Burtonwood, AB England; Wiesbaden AB, Germany; Wheelus AB, Tripoli; and Nicosia RAFB, Cyprus. At that time a major problem existed with the exhaust system of the Albatross' R-1820-76A Wright Cyclone engines. Nine cylinders emptied into six exhaust stacks and the clamps holding this system together had a bad habit of cracking and breaking apart. This then allowed the unsupported exhaust stacks to crack and break at the cylinder, creating a severe fire hazard-. Needless to say, we made off with every spare exhaust clamp we could lay our hands on. Another potentially fatal problem we learned the hard way. The SA-16A was equipped with 43D50 Hamilton Hydromatic Reversing Propellers. To permit propeller reversing during water operations there was no interrupt switch mounted on the landing gear such as that normally found on land planes. The propeller were put into reverse by retarding the throttles, located on the overhead quadrant between the pilots, and pushing them up into the reverse detente, which activated a prop-mounted switch which directed the throttles to reverse pitch. Pulling the throttles full back would give up to 70% of rated power for reverse. The prop-mounted switch was located externally on number one propeller blade. We discovered while flying between Greenland and Iceland on our trip back to Dhahran that a very small amount of moisture could keep this switch open and that when the props were in a low blade angle during cruise, the propeller could slip into reverse without any action by the pilot. We were at 8000 feet altitude when the number one engine went into reverse without any warning. The radically changed our attitude of flight! By the time the pilot, Captain Milton Connell, was able to push the feather button, the only action that would bring the propeller out of reverse in this emergency situation, we were passing through 2000 feet on our way to impact with the cold North Atlantic Ocean. I spent WWII in Greenland and on the North Atlantic Ocean with the U.S. Coast Guard, and I didn't want to spend any further time in that area, especially in a rubber raft! Captain Connell regained control and made it into Keflavik. Upon landing the switch was operating normally and the problem could not be duplicated. Only later did we discover the cause of the malfunction, but not before the same thing happened to us again over the Persian Gulf some months later. This problem was finally corrected by a major modification, remounting the switch internally in the propeller hub. But in those early days we could only keep our fingers crossed, for all the help that provided.

My ship! SA-16A 49-075 on the apron at Dhahran, 1950. This was the 22nd aircraft of this type in the Air Force inventory, and the first to go overseas. Notice the AN/APS 31 radar pod located just inboard of the left wing float. Later models had this radar fitted into the bow of the aircraft. This very aircraft is being

restored! Go

here

to read all about it and see the photos! Now that we had an aircraft which could land on water, much training was needed. Our water practice take-offs and landings took place in the Persian Gulf, one of the saltiest bodies of water on earth. Corrosion was a serious problem. The normal water supply at Dhahran was brackish and had to be distilled for drinking. The aircraft washdown procedure involved using the fire truck water supply to wash the salt of f , after which the distilled water supply from the 500-gallon white desert truck was used to wash off the corrosive brackish water. Later in October 1950, while on a training flight in support of our four man para-rescue team practicing an air and land rescue at one of the previously marked aircraft wrecks near the Kuwaiti border, we received word that a 1414th Base Flight C-47 had lost an engine on a flight from Asmara to Dhahran. The aircraft had made an emergency landing on a gravel plain in the desert east of the Saudi capital city, Riyadh. We reached the area and after a search in the late evening darkness, located the C-47 aircraft. We landed and loaded aboard the 23 crew and passengers, made an uneventful night take-off from the open desert gravel plain and brought everyone back to Dhahran. Flight mission time was ten and a half hours. Two days later a crew member aboard the US Navy tanker USS PECOS, suffering from internal injuries received during a fall, required evacuation to medical facilities ashore. After taking on maximum fuel, 675-gallons in the internal tanks and 600-gallons in two drop tanks, plus four ATO bottles, we were airborne for a flight to a rendezvous in the Arabian Sea over 1000 miles from Dhahran. On our arrival the PECOS made a continuous turn attempting to dampen Out two very large ground swells--the smaller swell quartering into the larger one. We circled the landing area several times and elected to attempt a landing on the crest of the larger swell. The APU was started and the portable bilge pumps were made ready just in case! Open sea landings were always a hazardous undertaking. On touch down onto the larger swell the aircraft bounced back into the air and landed in the trough between the two quartering swells. Capt. Connell pushed the throttles into reverse and applied full reverse power. We hit the water and stayed there. Attesting to the ruggedness of the SA-16A construction, no rivets popped and no leaks developed. The sea was running fairly high, but with little wind there were no white caps. However, getting the injured sailor, strapped in a stokes litter, from the large metal lifeboat into the plane proved to be a difficult task. From the aircraft a six-man, cabin-stowed life raft was put over the side, a mooring line secured and the raft inflated and allowed to drift to the life boat. The patient was transferred to the raft and hauled back to the SA-16A. Once taken aboard, the patient's litter was secured to the litter stowage rack, the raft deflated and brought aboard. The ATO bottles were removed from their storage well in the bilge between the wheel wells, installed on the ATO mounts on each aft door and everything made ready for an open-sea take-off. The pilot, with a lot of effort, taxied the aircraft onto the top of the large swell. Keeping the aircraft on the crest of this swell, he applied full power and at about 65 knots air speed fired the four ATO bottles for an extra 4000 pounds thrust for 15 seconds. We broke loose from the suction of the water and staggered into the air for our return to Dhahran. This flight lasted 12 1/2 hours. The patient was treated in the base hospital and, before being evacuated to a more sophisticated medical facility, came by Flight 'D' headquarters to give his personal thanks for a job well done. Thanksgiving Day, 1950, found us once again airborne for another open-sea landing and take-off in the Arabian Sea more than 1000 miles from Dhahran. A sailor on board the USS VALCOUR, the U.S. Navy's Middle East Force flagship, need to return to the U.S. for a serious family emergency. The 10-hour flight required a night open-sea landing, at that time the first of its kind for our new Albatross. The USS VALCOUR provided illumination with search lights, float lights, star shells and two life boats in the landing area. Fortunately the sea was very calm and the landing, transfer of the passenger and ATO take-off were basically routine. The most serious problem of the day was missing out on our Thanksgiving Day dinner. The USS VALCOUR did send over some first rate turkey sandwiches, which were very much appreciated. Late in 1950, the Air Weather Service established a detachment at Dhahran with three WB-29 aircraft. Although their aircraft had no serious problems, we flew almost weekly intercept mission to escort a WB-29 with at least one engine out. To see a Flight “D” rescue SA-16A providing close escort was a welcome sight to those weather fliers. When it came time for my rotation back to the U.S. in 1951, I was the only enlisted ground and aircrew member qualified in the SA-16A still stationed at Dhahran. As a result, I was extended for three additional months until a qualified replacement could be alerted and sent to Dhahran, with, of course, the permission of the King’s representative. Today Dhahran, Saudi Arabia is a large modern complex, but in 1950-1951 it was a truly remote assignment area and duty with Flight “D”, 7th Air Rescue Squadron, was n experience never to be forgotten. |

|

Copyright 2000 by Ted A. Morris |