Studying Our Living Planet

What is ecology?

When biologists want to talk about life on a global scale,

they use the term biosphere.

Biosphere

All life on Earth and all parts of the Earth in which

life exists, including land, water, and the atmosphere

The biosphere contains every organism, from bacteria living

underground to giant trees in rain forests, whales in polar seas, mold

spores drifting through the air—and, of course, humans. The biosphere

extends from about 8 kilometers above Earth’s surface to as far as 11 kilometers

below the surface of the ocean. |

|

|

The Science of Ecology

|

| Organisms in the biosphere interact with each other and

with their surroundings, or environment. The study of these interactions

is called ecology.

Ecology

The scientific study of interactions among organisms

and between organisms and their physical environment. |

|

| The root of the word ecology is the Greek word oikos,

which means “house.” So, ecology is the study of nature’s “houses” and

the organisms that live in those houses.

Interactions within the biosphere produce a web of interdependence

between organisms and the environments in which they live. Organisms

respond to their environments and can also change their environments, producing

an ever-changing, or dynamic, biosphere. |

|

|

Ecology and Economics

The Greek word oikos is also the root of the word

economics. Economics is concerned with human “houses” and human interactions

based on money or trade. Interactions among nature’s “houses” are

based on energy and nutrients. As their common root implies, human

economics and ecology are linked. Humans live within the biosphere

and depend on ecological processes to provide such essentials as food and

drinkable water that can be bought and sold or traded.

Levels of Organization

Ecologists ask many questions about organisms and their

environments. Some ecologists focus on the ecology of individual

organisms. Others try to understand how interactions among organisms

(including humans) influence our global environment. Ecological studies

may focus on levels of organization that include those shown in Figure

3–1.

|

|

|

Individual Organism

A species is a group of similar organisms

that can breed and produce fertile offspring. |

|

Population

A population is a group of individuals

that belong to the same species and live in the same area. |

|

|

|

Community

An assemblage of different populations that live together

in a defined area is called a community. |

|

Ecosystem

All the organisms that live in a place, together with

their physical environment, is known as an ecosystem. |

|

|

|

Biome

A biome is a group of ecosystems that share

similar climates and typical organisms. |

|

Earth

Our entire planet, with all its organisms and physical

environments, is known as the biosphere. |

What is ecology?

REVIEW & DO

NOW

Answer the following questions: |

| What is the biosphere?

What is ecology? |

|

| Name and define the six levels of organization

from the individual to the entire planet. |

|

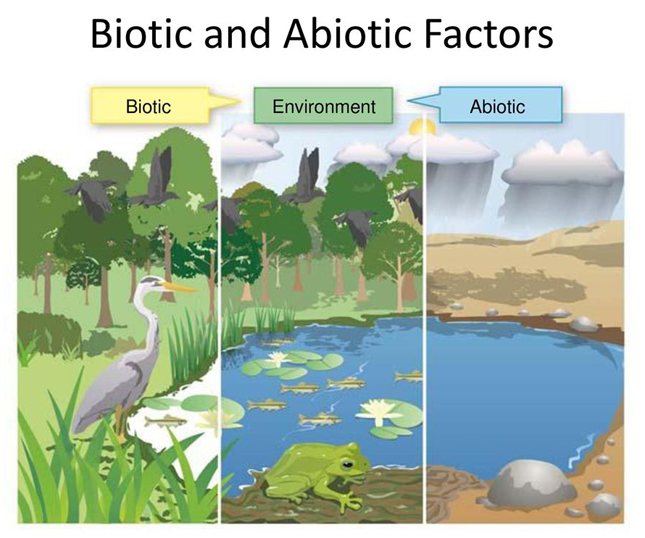

Biotic and Abiotic Factors

What are biotic and abiotic factors?

Ecologists use the word environment to refer

to all conditions, or factors, surrounding an organism. Environmental

conditions include biotic factors and abiotic factors, as shown below.

Biotic Factors

The biological influences on organisms are called biotic

factors.

Biotic Factor

Any part of the environment which is alive or that

comes from a living thing with which an organism might interact

Biotic factors relating to a bullfrog, for example, might

include algae it eats as a tadpole, insects it eats as an adult, herons

that eat bullfrogs, and other species that compete with bullfrogs for food

or space.

Abiotic Factors

Physical components of an ecosystem are called abiotic

factors.

Abiotic Factor

Any nonliving part of the environment, such as sunlight,

heat, precipitation, humidity, wind or water currents, and soil type

For example, a bullfrog could be affected by abiotic factors

such as water availability, temperature, and humidity.

Biotic and Abiotic Factors Together

The difference between biotic and abiotic factors may

seem to be clear and simple. But if you think carefully, you will

realize that many physical factors can be strongly influenced by the activities

of organisms. Bullfrogs hang out, for example, in soft “muck” along

the shores of ponds. You might think that this muck is strictly part

of the physical environment, because it contains nonliving particles of

sand and mud. But typical pond muck also contains leaf mold and other

decomposing plant material produced by trees and other plants around the

pond. That material is decomposing because it serves as “food” for

bacteria and fungi that live in the muck.

Taking a slightly wider view, the “abiotic” conditions

around that mucky shoreline are strongly influenced by living organisms.

A leafy canopy of trees and shrubs often shade the pond’s shoreline from

direct sun and protect it from strong winds. In this way, organisms

living around the pond strongly affect the amount of sunlight the shoreline

receives and the range of temperatures it experiences. A forest around

a pond also affects the humidity of air close to the ground. The

roots of trees and other plants determine how much soil is held in place

and how much washes into the pond. Even certain chemical conditions

in the soil around the pond are affected by living organisms. If

most trees nearby are pines, their decomposing needles make the soil acidic.

If the trees nearby are oaks, the soil will be more alkaline. This

kind of dynamic mix of biotic and abiotic factors shapes every environment.

What are biotic and abiotic factors?

REVIEW & DO

NOW

Answer the following questions: |

| What is the environment?

What are biotic factors?

Give an example of a biotic factor. |

|

What are abiotic factors?

Give an example of an abiotic factor. |

|

The Major Biomes

What abiotic and biotic factors characterize biomes?

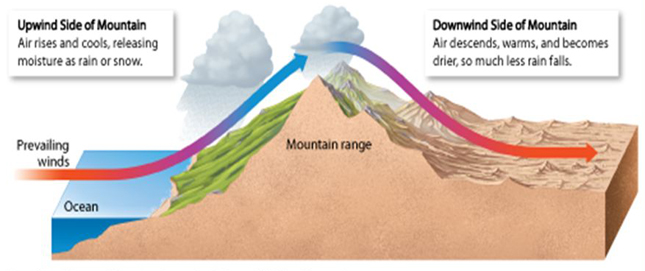

Latitude and the heat transported by winds are two factors

that affect global climate. States like Oregon, Montana, and Vermont

have different climates and biological communities, even though those states

are at similar latitudes and are all affected by prevailing winds that

blow from west to east. Why? The reason is because other factors,

among them an area’s proximity to an ocean or mountain range, can influence

climate.

Regional Climates

Oregon, for example, borders the Pacific Ocean.

Cold ocean currents that flow from north to south have the effect of making

summers in the region cool relative to other places at the same latitude.

Similarly, moist air carried by winds traveling west to east is pushed

upward when it hits the Rocky Mountains. This air expands and cools,

causing the moisture in the air to condense and form clouds. The

clouds drop rain or snow, mainly on the upwind side of the mountains—the

side that faces the winds, as seen below. West and east Oregon, then,

have very different regional climates, and different climates mean different

plant and animal communities.

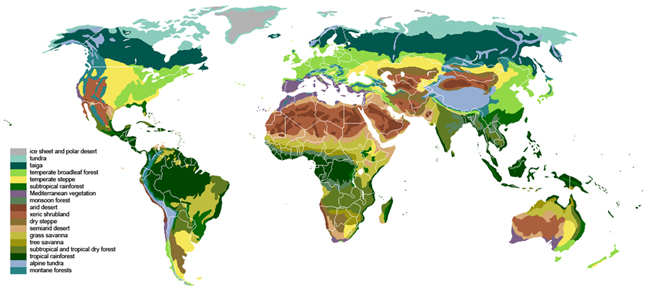

Defining Biomes

Ecologists classify Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems into

at least ten different groups of regional climate communities called biomes.

-

Biomes are described in terms of abiotic factors like

climate and soil type, and biotic factors like plant and animal life.

Major biomes include tropical rain forest, tropical dry forest,

tropical grassland/savanna/shrubland, desert, temperate grassland, temperate

woodland and shrubland, temperate forest, northwestern coniferous forest,

boreal forest/taiga, and tundra. Each biome is associated with seasonal

patterns of temperature and precipitation that can be summarized in a graph

called a climate diagram, like the one shown above. Organisms within

each biome can be characterized by adaptations that enable them to live

and reproduce successfully in the environment. The pages that follow

discuss these adaptations and describe each biome’s climate.

The distribution of major biomes is shown below.

Note that even within a defined biome, there is often considerable

variation among plant and animal communities. These variations can

be caused by differences in exposure, elevation, or local soil conditions.

Local conditions also can change over time because of human activity or

because of the community interactions described in this chapter and the

next.

Earth's Major Biomes

Tropical Rain Forest

|

| Tropical rain forests are home to more species

than all other biomes combined. As the name suggests, rain forests

get a lot of rain—at least 2 meters of it a year! Tall trees form a dense,

leafy covering called a canopy from 50 to 80 meters above

the forest floor. In the shade below the canopy, shorter trees and

vines form a layer called the understory. Organic matter

on the forest floor is recycled and reused so quickly that the soil in

most tropical rain forests is not very rich in nutrients. |

|

• Abiotic factors

Hot and wet year-round; thin, nutrient-poor soils subject

to erosion

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Understory plants compete for sunlight,

so most have large leaves that maximize capture of limited light.

Tall trees growing in poor shallow soil often have buttress roots for support.

Epiphytic plants grow on the branches of tall plants as opposed to soil.

This allows epiphytes to take advantage of available sunlight while obtaining

nutrients through their host.

Animal life: Animals are active all year.

Many animals use camouflage to hide from predators; some can change color

to match their surroundings. Animals that live in the canopy have

adaptations for climbing, jumping, and/or flight. |

|

Tropical Dry Forest

|

| Tropical dry forests grow in areas where

rainy seasons alternate with dry seasons. In most places, a period

of rain is followed by a prolonged period of drought.

• Abiotic factors

Warm year-round; alternating wet and dry seasons; rich

soils subject to erosion |

|

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Adaptations to survive the dry season

include seasonal loss of leaves. A plant that sheds its leaves during

a particular season is called deciduous. Some plants

also have an extra thick waxy layer on their leaves to reduce water loss,

or store water in their tissues.

Animal life: Many animals reduce their need for

water by entering long periods of inactivity called estivation.

Estivation is similar to hibernation, but typically takes place during

a dry season. Other animals, including many birds and primates, move

to areas where water is available during the dry season. |

|

Tropical Grassland

|

The Savanna or Shrubland

This biome receives more seasonal rainfall than deserts

but less than tropical dry forests. Grassy areas are spotted with

isolated trees and small groves of trees and shrubs. Compacted soils,

fairly frequent fires, and the action of large animals—for example, rhinoceroses

and elephants—prevent some areas from turning into dry forest. |

|

• Abiotic factors

Warm; seasonal rainfall; compact soils; frequent fires

set by lightning

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Plant adaptations are similar to those

in the tropical dry forest, including waxy leaf coverings and seasonal

leaf loss. Some grasses have a high silica content that makes them

less appetizing to grazing herbivores. Also, unlike most plants,

grasses grow from their bases, not their tips, so they can continue to

grow after being grazed.

Animal life: Many animals migrate during the dry

season in search of water. Some smaller animals burrow and remain

dormant during the dry season. |

|

Desert

|

| Deserts have less than 25 centimeters of

precipitation annually, but otherwise vary greatly, depending on elevation

and latitude. Many deserts undergo extreme daily temperature changes,

alternating between hot and cold.

• Abiotic factors

Low precipitation; variable temperatures; soils rich

in minerals but poor in organic material |

|

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Many plants, including cacti, store

water in their tissues, and minimize leaf surface area to cut down on water

loss. Cactus spines are actually modified leaves. Many desert

plants employ special forms of photosynthesis that enable them to open

their leaf pores only at night, allowing them to conserve moisture on hot,

dry days.

Animal life: Many desert animals get the water

they need from the food they eat. To avoid the hottest parts of the

day, many are nocturnal—active only at night. Large or elongated

ears and other extremities are often supplied with many blood vessels close

to the surface. These help the animal lose body heat and regulate

body temperature. |

|

Temperate Grassland

|

| Plains and prairies, underlain by fertile

soils, once covered vast areas of the midwestern and central United States.

Periodic fires and heavy grazing by herbivores maintained plant communities

dominated by grasses. Today, most have been converted for agriculture

because their soil is so rich in nutrients and is ideal for growing crops. |

|

• Abiotic factors

Warm to hot summers; cold winters; mode rate seasonal

precipitation; fertile soils; occasional fires

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Grassland plants—especially grasses,

which grow from their base—are resistant to grazing and fire. Dispersal

of seeds by wind is common in this open environment. The root structure

and growth habit of native grassland plants helps establish and retain

deep, rich, fertile topsoil.

Animal life: Because temperate grasslands are such

open, exposed environments, predation is a constant threat for smaller

animals. Camouflage and burrowing are two common protective adaptations. |

|

|

Temperate Woodland

In open woodlands, large areas of grasses and wildflowers

such as poppies are interspersed with oak and other trees. Communities

that are more shrubland than forest are known as chaparral. Dense

low plants that contain flammable oils make fire a constant threat.

• Abiotic factors

Hot dry summers; cool moist winters; thin, nutrient-poor

soils; periodic fires |

|

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Plants in this biome have adapted

to drought. Woody chaparral plants have tough waxy leaves that resist

water loss. Fire resistance is also important, although the seeds

of some plants need fire to germinate.

Animal life: Animals tend to be browsers—meaning

they eat varied diets of grasses, leaves, shrubs, and other vegetation.

In exposed shrubland, camouflage is common. |

|

Temperate Forest

|

| Temperate forests are mostly made up of deciduous

and evergreen coniferous trees. Coniferous trees, or

conifers, produce seed-bearing cones, and most have leaves shaped like

needles, which are coated in a waxy substance that helps reduce water loss.

These forests have cold winters. In autumn, deciduous trees shed

their leaves. In the spring, small plants burst from the ground and

flower. |

|

| Fertile soils are often rich in humus,

a material formed from decaying leaves and other organic matter.

• Abiotic factors

Cold to moderate winters; warm summers; year-round precipitation;

fertile soils

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Deciduous trees drop their leaves

and go into a state of dormancy in winter. Conifers have needlelike

leaves that minimize water loss in dry winter air.

Animal life: Animals must cope with changing weather.

Some hibernate; others migrate to warmer climates. Animals that do

not hibernate or migrate may be camouflaged to escape predation in the

winter when bare trees leave them more exposed. |

|

Northwestern Coniferous Forest

|

| Mild moist air from the Pacific Ocean influenced

by the Rocky Mountains provides abundant rainfall to this biome.

The forest includes a variety of conifers, from giant redwoods to spruce,

fir, and hemlock, along with flowering trees and shrubs such as dogwood

and rhododendron. Moss often covers tree trunks and the forest floor.

Because of its lush vegetation, the northwestern coniferous forest is sometimes

called a “temperate rain forest.” |

|

• Abiotic factors

Mild temperatures; abundant precipitation in fall, winter,

and spring; cool dry summers; rocky acidic soils

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Because of seasonal temperature variation,

there is less diversity in this biome than in tropical rain forests.

However, ample water and nutrients support lush, dense plant growth.

Adaptations that enable plants to obtain sunlight are common. Trees

here are among the world’s tallest.

Animal life: Camouflage helps insects and ground-dwelling

mammals avoid predation. Many animals are browsers—they eat a varied

diet—an advantage in an environment where vegetation changes seasonally. |

|

Boreal Forest

|

| Dense forests of coniferous evergreens along

the northern edge of the temperate zone are called boreal forests, or taiga.

Winters are bitterly cold, but summers are mild and long enough to allow

the ground to thaw. The word boreal comes from the Greek word for

“north,” reflecting the fact that boreal forests occur mostly in the northern

part of the Northern Hemisphere. |

|

• Abiotic factors

Long cold winters; short mild summers; moderate precipitation;

high humidity; acidic, nutrient-poor soils

• Biotic factors

Plant life: Conifers are well suited to the boreal-forest

environment. Their conical shape sheds snow, and their wax-covered

needlelike leaves prevent excess water loss. In addition, the dark

green color of most conifers absorbs heat energy.

Animal life: Staying warm is the major challenge

for animals. Most have small extremities and extra insulation in

the form of fat or downy feathers. Some migrate to warmer areas in

winter. |

|

Tundra

|

| The tundra is characterized by permafrost,

a layer of permanently frozen subsoil. During the short cool summer,

the ground thaws to a depth of a few centimeters and becomes soggy.

In winter, the top layer of soil freezes again. This cycle of thawing

and freezing, which rips and crushes plant roots, is one reason that tundra

plants are small and stunted. Cold temperatures, high winds, a short

growing season, and humus-poor soils also limit plant height. |

|

• Abiotic factors

Strong winds; low precipitation; short and soggy summers;

long, cold, dark winters; poorly developed soils; permafrost

• Biotic factors

Plant life: By hugging the ground, mosses and

other low-growing plants avoid damage from frequent strong winds.

Seed dispersal by wind is common. Many plants have adapted to growth

in poor soil. Legumes, for example, have nitrogen-fixing bacteria

on their roots.

Animal life: Many animals migrate to avoid long

harsh winters. Animals that live in the tundra year-round display

adaptations, among them natural antifreeze, small extremities that limit

heat loss, and a varied diet. |

|

Other Land Areas Not Easily Classified

Some land areas do not fall neatly into one of the major

biomes.

-

Because they are not easily defined in terms of a typical

community of plants and animals, mountain ranges and polar ice caps are

not usually classified into biomes.

Mountain Ranges

Mountain ranges exist on all continents and in many biomes.

On mountains, conditions vary with elevation. From river valley to

summit, temperature, precipitation, exposure to wind, and soil types all

change, and so do organisms. If you climb the Rocky Mountains in

Colorado, for example, you begin in a grassland. |

|

|

|

| You then pass through pine woodland and then a forest

of spruce and other conifers. Thickets of aspen and willow trees

grow along streambeds in protected valleys. Higher up, soils are

thin. Strong winds buffet open fields of wildflowers and stunted

vegetation resembling tundra. Glaciers are found at the peaks of

many ranges. |

|

Polar Ice Caps

| Polar regions border the tundra and are cold year-round.

Plants are few, though some algae grow on snow and ice. Where rocks

and ground are exposed seasonally, mosses and lichens may grow. Marine

mammals, insects, and mites are the typical animals. In the north,

where polar bears live, the Arctic Ocean is covered with sea ice, although

more and more ice is melting each summer. |

|

|

In the south, the continent of Antarctica, inhabited by many

species of penguins, is covered by ice nearly 5 kilometers thick in places.

What abiotic and biotic factors

characterize biomes?

REVIEW & DO

NOW

Answer the following questions: |

| List and distinguish Earth's ten major biomes. |

|

| Why are mountain ranges and polar ice caps not classified

as biomes? |

|

Ecological Methods

What methods are used in ecological studies?

Some ecologists, like the one in Figure 3–3, use measuring

tools to assess changes in plant and wildlife communities. Others

use DNA studies to identify bacteria in marsh mud. Still others use

data gathered by satellites to track ocean surface temperatures.

Regardless of their tools, modern ecologists use three

methods in their work: observation, experimentation, and modeling.

Each of these approaches relies on scientific methodology to guide inquiry.

Observation

Observation is often the first step in asking ecological

questions. Some observations are simple: Which species live here?

How many individuals of each species are there? Other observations are

more complex: How does an animal protect its young from predators?

These types of questions may form the first step in designing experiments

and models.

| Experimentation

Experiments can be used to test hypotheses. An ecologist

may, for example, set up an artificial environment in a laboratory or greenhouse

to see how growing plants react to different conditions of temperature,

lighting, or carbon dioxide concentration. Other experiments carefully

alter conditions in selected parts of natural ecosystems. |

|

|

Modeling

Many ecological events, such as effects of global warming

on ecosystems, occur over such long periods of time or over such large

distances that they are difficult to study directly. Ecologists make

models to help them understand these phenomena. Many ecological models

consist of mathematical formulas based on data collected through observation

and experimentation. Further observations by ecologists can be used

to test predictions based on those models.

What methods are used in ecological

studies?

REVIEW & DO

NOW

Answer the following questions: |

| What are three of the methods used by ecologists to study

life on Earth? |

|

|

|