REFLECTIONS

Articles Archive --

Topical Index --

Textual Index

by Al Maxey

Issue #814 -- January 11, 2021

**************************

Creeds grow so thick along the

way, their boughs hide God.

Lizette Woodworth Reese {1856-1935}

**************************

The Apostles' Creed

Ancient Affirmation of Faith

Mankind, regardless of time, place, and culture, has always had a tendency to try and encapsulate its fundamental religious and spiritual beliefs

and convictions in brief forms easily remembered. These have been called creeds, confessions, and canons

of faith. The obvious shortcoming of any such creed, confession, or canon is that no single statement of belief will ever fully express the fulness

of faith of all mankind. Our understandings and convictions regarding our Creator and His will for His creation differ greatly from

person to person, nation to nation, and culture to culture. Thus, over the course of human history countless creeds have appeared. The

Oxford English Dictionary defines a "creed" (as it pertains to those who follow Jesus) as "a brief formal summary of the Christian faith."

Yet, it is quite clearly so much more, for in these statements "the element of personal trust in God is prominent. A creed is thus something more

than a symposium of accepted belief or even an epitome of divinely revealed truth. It involves the existential commitment of the confessor to God"

[The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 1, p. 805].

Mankind, regardless of time, place, and culture, has always had a tendency to try and encapsulate its fundamental religious and spiritual beliefs

and convictions in brief forms easily remembered. These have been called creeds, confessions, and canons

of faith. The obvious shortcoming of any such creed, confession, or canon is that no single statement of belief will ever fully express the fulness

of faith of all mankind. Our understandings and convictions regarding our Creator and His will for His creation differ greatly from

person to person, nation to nation, and culture to culture. Thus, over the course of human history countless creeds have appeared. The

Oxford English Dictionary defines a "creed" (as it pertains to those who follow Jesus) as "a brief formal summary of the Christian faith."

Yet, it is quite clearly so much more, for in these statements "the element of personal trust in God is prominent. A creed is thus something more

than a symposium of accepted belief or even an epitome of divinely revealed truth. It involves the existential commitment of the confessor to God"

[The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 1, p. 805].

In other words, creeds, confessions, and articles of faith are more than mere expressions of what we believe, they are also personal declarations

of who we are or perceive ourselves to be in relation to our God and our fellow believers, revealing our very purpose for being and our hope for

the future. As already noted, since the time of Christ Jesus a large number of formal creeds have been written and adopted by the various groups

within Christendom, each seeking to capture the fundamental convictions of the religious party that penned them. These creeds quickly took on a

life of their own, becoming far more regulative than reflective. Those who differed with the particulars of a group's creed or confession or articles

of faith were deemed to be unbelievers, and thus unfit for fellowship within that group. Creeds and confessions, therefore, became

a tool for separating the chaff from the wheat: they excluded rather than included. Barton W. Stone (1772-1844), one of

the leading figures in our own Stone-Campbell Movement, had nothing but disgust for creeds, which he regarded as "nuisances of

religious society, and the very bane of Christian unity" [The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement, p. 252]. Stone expressed

his contempt in quite some detail in his Apology of the Springfield Presbytery (written in 1804), stating that creeds were "instruments

of ecclesiastical tyranny, enslaving the free consciences of Christians and spawning sectarianism" [ibid]. Before he could be ordained

a Presbyterian pastor he was required to swear to The Westminster Confession, which was the doctrinal norm of English-speaking

Presbyterians. He finally agreed to do so (in order to be ordained), yet stated he would only adopt the creed "as far as I see it consistent with the

Word of God" [ibid].

During the Reformation period alone, one will find numerous creeds, each somewhat different, each reflecting, in its unique language, the

particular beliefs and practices of the Christian sect that produced it. There is The Augsburg Confession (1530), The Waldensian

Declaration of Faith (1532), The First Helvetic Confession (1536), The Geneva Confession (1537), The

Gallican Confession (1559), The Thirty-nine Articles (1571) of the Church of England, The Canons of the Synod of

Dort (1619), and on and on we could go. This doesn't even take into account the much earlier creeds of Christendom, such as The

Nicene Creed (325 A.D.), The Chalcedonian Creed (451 A.D.), The Athanasian Creed (500 A.D.), just to name a

few. Many of these creeds, and those that came afterward, were not only designed to list a group's beliefs, but also to expose and oppose some

doctrine or practice disapproved of by the group/sect. Thus, they quickly became a tool for dividing Christian brethren rather than

uniting them. The British poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892), who was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen

Victoria's reign, wrote, "There lives more faith in honest doubt, believe me, than in half the creeds." Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909), an

English poet, playwright, novelist, and critic, asked this haunting question, "What ailed us, O gods, to desert you for creeds that refuse and restrain?"

The American poet Lizette Woodworth Reese (1856-1935) observed, "Creeds grow so thick along the way, their boughs hide God." She most

definitely has a point!

Not a few biblical scholars, as well as many lesser-known disciples of Christ, have long insisted that we tend to become so distracted by all the

religious trappings, ceremonies, and creeds that we lose sight of the simplicity of our Lord's calling. Ella Wheeler Wilcox (1850-1919), an American

author and poet, wrote, "So many gods, so many creeds, so many paths that wind and wind, when just the act of being kind is all this sad world needs."

Cincinnatus Heine Miller (1837-1913), better known by his pen name Joaquin Miller, was a colorful American poet, author, and frontiersman. He is

nicknamed the "Poet of the Sierras" after the Sierra Nevada, about which he wrote in his Songs of the Sierras. In his work titled

The Tale of the Tall Alcalde he wrote, "I do not question school nor creed of Christian, Protestant, or Priest; I only know that creeds

to me are but new names for mystery, that good is good from east to east, and more I do not know nor need to know, to love my neighbor well."

We don't need a creed or confession to practice kindness and love. We need a change of heart! And yet, there is a place for such

creeds and confessions of faith in the church. "Christian believers formed the habit, when they met, of reciting their common faith, and this recitation

assumed a fixed rhythmical form. Its beginnings are visible in the NT - see Matthew 16:16; 28:19; Romans 10:9-10; 1 Corinthians 8:6; 12:3;

Ephesians 4:4-6; 1 Timothy 3:16; 1 John 4:2; and further back, for the OT and the Synagogue, in the Shema of Deuteronomy 6:4"

[Hastings' Dictionary of the Bible, e-Sword].

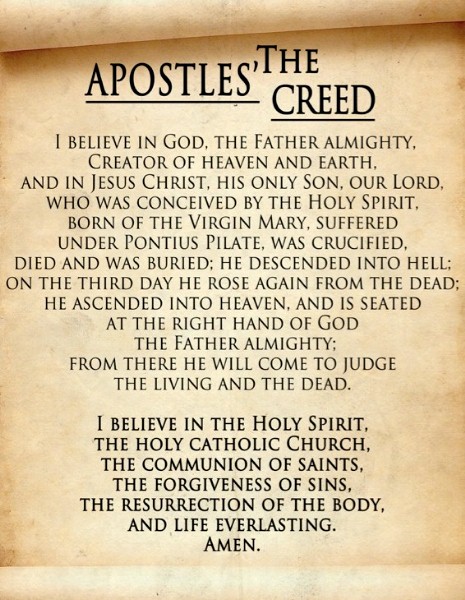

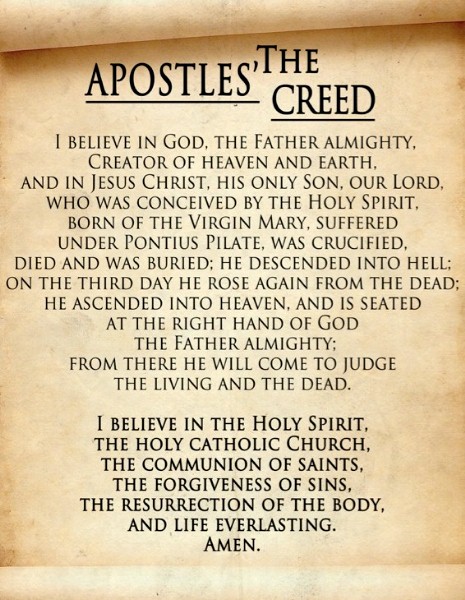

Oh, for a creed that all would find reflective of eternal Truth and genuine Faith. Something simple, yet profound in that simplicity. A

statement outside the Scriptures (more than just quoting a verse), yet entirely consistent with the Scriptures. A great many

Christians over the centuries believe that such a creed does exist; that it is the creed known as The Apostles' Creed. It has

indeed been adopted by believers of all Christian persuasions, both Catholic and Protestant, high church and low church, ancient and modern. The

reformer Martin Luther (1483-1546) said this about this ancient creed, "Christian truth could not possibly be put into a shorter and clearer statement."

John Calvin (1509-1564) agreed, saying that "it gives, in clear and succinct order, a full statement of our faith, and everything which it contains is

sanctioned by the sure testimony of Scripture" [The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 1, p. 809]. One online student of

the Scriptures and Church History said, "This creed is called the apostles' creed not because it was produced by the apostles themselves,

but because it contains a brief summary of their teachings. It sets forth their doctrine in sublime simplicity, in unsurpassable brevity, in beautiful order,

and with liturgical solemnity. More than any other Christian creed, it may justly be called an ecumenical symbol of faith."

This creed "itself is not, of course, of apostolic origin. Its title ('The Apostles' Creed') is first found around 390 A.D., and it

was soon after this that the legend appeared. The legend is a quaint one assuring that each of the twelve apostles contributed a special article"

[The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible, vol. 1, p. 220]. Some have broken the creed down into twelve distinct sections,

and have then assigned one of the Twelve (with Matthias replacing Judas Iscariot) to each section. Rufinus of Aquileia (345-411 A.D.) stated,

"So the apostles met together in one spot and, being filled with the Holy Spirit, compiled this brief token ... each making the contribution he thought

fit; and they decreed that it should be handed out as standard teaching to believers." Although this is an interesting aspect of one's study of this

creed, there is absolutely no evidence to support such a legend, and it pretty much faded away by the time of the Renaissance. As for the first

actual historical appearance of the title (The Apostles' Creed), that occurred in a letter which most scholars believe was written by

Ambrose, from the Council of Milan, to Pope Siricius about 390 A.D. Because this ancient creed has been used by so many different

Christian groups, it has understandably been slightly modified over the centuries to better reflect the beliefs of those churches and denominations

in which it is used. There is a Catholic version, a Lutheran version, a Presbyterian version, etc. The traditional

version of this creed follows:

As one reads and reflects upon the wording of this ancient creed (and in its earliest form it can be fairly confidently dated back to the second

century), which admittedly has undergone some revision over the centuries, several things stand out to the observant reader. First, as

Wikipedia rightly observes, "The Apostles' Creed is trinitarian in structure, with sections affirming belief in God the Father, God

the Son, and God the Holy Spirit." This obvious focus on the Trinity (which is a whole study in itself, and a difficult one at that) has bothered

a good many Christians over the years, for there is a growing number of believers who have some serious doubts about trinitarian theology.

It is not our purpose here to enter into that debate, but merely to mention that this debate does exist, and that it causes many

Christians to view this ancient creed less favorably. Further, "because of the early origin of its original form, the Apostles' Creed does not

address some Christological issues defined in the Nicene and other Christian creeds. It thus says nothing explicitly about the divinity of either

Jesus or the Holy Spirit. Nor does it address many other theological questions which became objects of dispute centuries later"

[Wikipedia]. This too has bothered some Christians, although it shouldn't, for it should be remembered that this is one of the very

first written creeds of the early church, thus it appeared long before many of the great theological debates with which we today are quite familiar.

If we fail to keep in mind its historical context, we can easily come to some false conclusions as to its worth as an historical and spiritual document

of the church.

For those who might wish to know my own personal feelings about this creed, and whether or not I would recite this creed as a true representation

of my own beliefs and convictions, my response is: In its traditional form (as in the graphic above), I agree with 99% of it, and

in its revised form, I agree with it 100%. My one objection, and this is the most highly contested line in this creed, is the

statement: "He descended into Hell." That is absolutely false. Nowhere in Scripture is this taught. The passage that serves as the

basis of this statement is 1 Peter 3:19 (although I should say that it is a misunderstanding of this verse that prompted this

false teaching). I have dealt with this in some depth in Reflections #83

("Preaching to the Prisoners: A Critical Analysis of 1 Peter 3:18-20"). R. C. Sproul (1939-2017), an American theologian and pastor,

wrote, "People are making a lot of assumptions when they consider that this (verse) is a reference to 'hell,' and that Jesus went there

between His death and His resurrection." In many of the revisions to The Apostles' Creed, this line has been replaced with: "He

descended to the dead," thus indicating that Jesus was placed in a grave/tomb. Also, I should probably point out that almost a decade ago I did a

Reflections article on The Apostles' Creed, with the majority of that study focusing on this one line in the creed (my current

issue of Reflections seeks to present a somewhat broader evaluation). For those who might like to go back and read the earlier study

I did, that issue is: Reflections #488 (dated June 9, 2011).

Another line in The Apostles' Creed that has caused some confusion is: "...the holy catholic Church." Specifically, it

is the word "catholic." Again, this confusion is caused by a simple misunderstanding of the term employed. The word "catholic" just means

"universal" - it is a reference to "the whole church," NOT a reference to the denomination known as the Roman

Catholic Church. To avoid this misunderstanding, some Protestant denominations have changed the wording of this line of the

creed to read: "...the holy Christian church." Dr. Timothy George (b. 1950), a Harvard educated Southern Baptist theologian,

wrote, "When we say that we 'believe in the holy catholic church,' we are confessing that Jesus Christ Himself is the church's one

foundation, that all who truly trust in Him as Savior and Lord are by God's grace members of this church, and that the gates of hell shall never prevail

against it." When we properly understand the meaning of "catholic" in this creed, none of us should have any problem at all with this particular line.

As another interesting tidbit: in the Roman Catholic versions of this creed, the word "Church" has an upper case "C", while in the Protestant

versions of the creed, the word "church" generally uses the lower case "c" instead. With this in mind, you might find my following two studies

to be of interest: "Sectarianism's C-ism Schism: Upper Case or Lower Case Church?"

(Reflections #520) and "True Church, True Name: Reflecting on Romans

16:16b" (Reflections #536).

Yet another "problem" line within this creed for some Christians is: "...the communion of saints." Once again, this is largely a Protestant vs. Catholic

matter: some in the former group being convinced that the phrase is promoting the view that the living can "commune" with departed "saints," even praying

to these "saints" (who have been elevated to "sainthood") for some kind of intervention or deliverance (a major teaching and practice of Roman

Catholicism). A few have even speculated that this is a reference to the Lord's Supper (which some call "Communion"). The phrase is not

referring to either, however. It simply speaks of that which all those who are redeemed (past, present, and future) share in common: a blessed

salvation by grace through faith that elevates us all spiritually from sinner to saint, and which, for those presently living, provides the additional blessing

of a loving fellowship with one another here on earth. I thought the website known as "CompellingTruth.Org" did an excellent job of explaining this:

"The Apostles' Creed refers to communion of the saints in reference to all believers, past and present, who share in salvation in Jesus

Christ. ... The idea of communion also emphasizes fellowship or community. In other words, communion of the saints includes the idea of living in

unity with other believers. One of the important aspects of the ancient creeds such as The Apostles' Creed is the unity that these early

statements of faith provided for believers from various locations and backgrounds. A Christian from any part of the world could affirm the same words,

enjoying a common unity found in the essentials of the Christian faith in the form of a creed. Still today, the words of The Apostles' Creed

are recited around the world by Christians of many backgrounds. Its words offer an early and important summary of Christian beliefs that has stood

the test of time." I think that sums it up quite nicely.

***************************

All of my materials (books, CDs, etc. - a full listing

of which can be found on my Web Site) may now

be ordered using PayPal. Just click the box above

and enter my account #: almaxey49@gmail.com

***************************

Readers' Reflections

From a Reader in California:

Al, I would like your thoughts on something. David, in Psalm 63:2, speaks of perceiving God's power and glory in His sanctuary. Then in Revelation

21:3 we find a voice from heaven declaring, "Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and He will dwell with them." My thinking is: God's power

and glory are "displayed" (shown) in His tabernacle, His sanctuary, which is our body. Since we are the "temple" of the Holy Spirit, then

wouldn't it be true that God's power and glory are manifested in us?! Am I on the right or wrong track here? Your thoughts on, and even

correction of, my interpretation would be appreciated. Thank you very much. Happy New Year to you and all your family, and may God continue to

bless all of you.

Although God made provision under prior covenants for the display of His power and glory, thereby

providing visible evidence of His presence with mankind (most notably through the tabernacle and then the temple - Acts 7:44-47), it was

never His intent that these would be the epitome of that manifest divine presence. Ultimately, that power and glory would be made manifest to

the world through His Son Jesus and then through a personal indwelling of His "called out ones." As Stephen declared, "The Most High

does not dwell in houses made by human hands" (Acts 7:48). In our present dispensation, God's "sanctuary" (Greek: "naos") is

within His people, both individually and corporately. It is important to note (as the apostle Paul does in 1st Corinthians 3:16-17; 6:19-20) that the

Lord indwells both (the individual disciple and the church as a whole) in a very unique way. He is in me personally, and He is also in

the universal Body of Christ (the church). Both of these intimate indwellings then become daily visible evidences of His power and glory. I dealt

with this concept more fully in my study titled "A Sanctuary of the Spirit: A Study of the Individual/Corporate Naos of the Indwelling

Holy Spirit" (Reflections #332). So, my answer to this beloved brother in

California, whom I have known for many years, is, "Yes, you are most definitely on the right track!" -- Al Maxey

[NOTE: After sending my above response to this reader, I received back the following

email from him: "Al, Thank you very much for your response, and for your very enlightening comments! One great thing I like about you is

that I am privileged to have personal access to you when I have questions. You have a whole world of very well-studied, well-written, and

well-catalogued resource materials that you yourself have written. Your work is a library of knowledge that you have made easily accessible

to all, and it should endure for a 'didactic eternity.' I love it that you have a Reflections article for nearly every subject under the

sun - well, at least those subjects from which any serious student of the Bible and truth-seeker can greatly profit. Again, thank you very much

for everything you do!"]

From a Reader in Georgia:

Happy New Year, Al. Our daughter posted a YouTube link to her Facebook page, along with some great comments, a few

days ago. The link is to the 47 minute presentation "Going to Hell in a Nutshell" by Greg

Boyd. Greg's views are almost exactly like yours on the nature of hell, and also on the destiny of those who are a "law unto themselves" (Romans

2:14). I think my daughter and her husband were happy to hear Greg agree with your teaching on these topics, which teaching I shared with them

some years ago. Al, you have been a tremendous help both to me and to my family. May God richly bless you and your family in 2021.

From a Reader in Nigeria, Africa:

I have a couple of questions. For what reason were Sodom and Gomorrah destroyed? I read your article "The Nature/Nurture Dilemma:

A Reflective, Respectful Response to Saints Struggling with Homosexuality"

(Reflections #305), and I agree that tendencies and actual practice aren't the

same thing. So, can someone say that homosexuality was among the sins that caused the destruction of these cities? Some have said that it was

only for "lack of hospitality" that they were destroyed. Also, what does "strange flesh" mean in the Jude 7 passage? Another question: A professor

told me that the reason Christians do good is because they hope for a reward. He says that such a motive is not selfless, but rather is

based on "what I can get," as well as a fear of punishment if I don't do good. How do I respond to this argument?

As for the sins of Sodom and Gomorrah (which are listed for us, by the way, in Ezekiel 16:49-50) and

the "strange flesh" reference in Jude 7, I have dealt with them in my study titled "The Sins Of Sodom: Their Five Greatest Failings as

Revealed in Ezekiel 16:49-50" (Reflections #65). As for the comment by

one of this reader's professors, I would tell that professor that he is partly right in his assessment. There are indeed a great many people who

"join up" because they see it as a way of achieving some personal gain. There are also, sadly, quite a few others who

profess to be followers of Christ who are "Christians" for almost no other reason than they fear the consequences of not

being so. It is not so much that they long for heaven as they fear hell. Such persons are truly "Christians" in name only. God is not looking for

self-serving or fearful followers; God desires faithful sons and daughters who love Him, and who serve Him not out of fear or a desire

for some reward, but out of love and

reverence. Those are the true Christ-followers, for they are "Christ-like" in nature and practice, and their motivation is love. --

Al Maxey

From a Reader in Oklahoma:

Greetings, Al. Long time, no see. I just happened upon a recent Reflections of yours, and you left me confused. It was titled

"Our Obligation to Our Oppressors: Jeremiah's Difficult Directive to the Dispersed"

(Reflections #810). I haven't read everything you've written about the topic of

church and politics, but I couldn't let this slide without responding, so that maybe you could clarify what you wrote. Also, I have no intention of

getting into petty arguments about Christians holding public office or serving in local/national governments. Here is what you wrote in paragraph

nine of the above article: "There are those who suggest that we, as Christians, should never involve ourselves in the political process of the nations

in which we live. I could not disagree more!!" Al, let me say this as clearly as I can: there is no place for politics in the pulpit or in the

meetings of the organized church! Or do I need to remind you of how "well" the church "served" the conflict of 1861-1865? And let me tell you, it's

not serving this current conflict in our nation well either, even though we are not stabbing one another with bayonets ... at least, not yet!

Let me make an important initial observation here: my statement and his subsequent declaration are NOT

in opposition to one another. He stated that "there is no place for politics in the pulpit or in the meetings of the organized church." Okay,

but that isn't what I was saying. I wasn't suggesting that we need to bring politics into our churches and pulpits; I was suggesting that Christians need

to insert themselves into the political processes of a nation so as to be a positive leavening influence. No, we should NOT bring the various workings

of the secular societies in which we live INTO the church, but we must not fail to insert ourselves into the world around us and let our

light shine in the darkness. It's hard for yeast to affect the dough if the yeast remains in the package. Same principle for the people of God

living on planet Earth. This doesn't mean that we forsake our responsibilities and duties as disciples of Christ, but neither should we refrain from

seeking to influence the various elements of our nation and its institutions with far more noble ideals and insights than the world will ever provide.

I agree that the church, and individual disciples, for the most part, did not have a very positive impact during the years of the so-called

"Civil War." On the other hand, they played an extremely important and very positive role during our American Revolution. I would refer this reader

to my study titled "The Black Robe Regiment: The Pastor-Patriots of the Revolution"

(Reflections #547). I do agree with this reader, however, that it is rarely wise for

pastors to turn their pulpits into political platforms for the purpose of promoting one party or the other, or one candidate or the other. Trying to be a

leavening force in our communities is one thing; seeking to "preach politics" is another. I have addressed this in my article "Pastors Politicking

from Pulpits: May Pastors Publicly Endorse Politicians?" (Reflections #546).

Part of the problem is that many simply don't understand the role of the church as it interacts with the countries and cultures in which its people are

dwelling. We hear the old cry of "separation of church and state," and yet that whole topic is woefully misunderstood by most people. I have sought

to provide a clearer analysis of that in my article "Church and State: May Disciples of Jesus Christ Participate in the Political Process?"

(Reflections #211). I hope these studies will help clarify my position for this

reader in Oklahoma.

-- Al Maxey

From a Reader in Canada:

Greetings, Al. What does "soul-damning fall from grace" mean?! If I sin grievously against God, I am not damned by Him, but I rest in

the assurance that I will be corrected by Him so as to bring me to repentance and return me to covenant faithfulness in serving and loving Him with

all my being. You used the above phrase in paragraph seven of Reflections #813

("Sad Saga of a Soused Sailor: Reflecting on the Strange Account of Noah Naked and Drunk Inside His Tent").

In Galatians 5:4 the apostle Paul warns disciples of Christ in very forceful language that if they seek

their justification and salvation through human effort, works of some legal code, and/or the traditions of mere men over eternal Truth, then they are

severed from Christ Jesus and are fallen from grace. A "fall from grace," however, is rarely some single sinful act (thank the Lord, for

we all sin daily in our lives: this is just part of the human condition). Rather, those who are truly fallen from grace, and thus severed

from Christ, are those who willfully and continually reject God's grace, and who knowingly choose

to walk in darkness rather than in the Light. In the epistle to the Hebrews we read, "For if we go on sinning willfully

after receiving the knowledge of the truth, there no longer remains a sacrifice for sins" (Hebrews 10:26), but rather a terrifying expectation of judgment

and punishment, for by such "willful" and "continual" attitudes and actions we "trample under foot the Son of God, and have regarded as unclean the

blood of the covenant by which we were sanctified, and insult the Spirit of grace" (vs. 29). Yes, this is "soul-damning," which the above inspired

writers make abundantly clear. Our sins of weakness are one thing (and Paul greatly lamented his own in the latter part of Romans 7), but one who

knowingly, continually, and willfully rejects God and His blessings is truly fallen from that grace and severed from Christ Jesus ... and

that is a deadly condition. Yes, one may not be so far gone that he/she cannot return in repentance to the Lord (as did the prodigal son),

and the Father will always welcome them back. But the danger is that one who chooses freely to LEAVE the Lord's embrace, so that he/she might

embrace the world, CAN and too often DOES reach a point where repentance is for them beyond reach (by their choice,

not by His). This is powerfully spelled out in Hebrews 6:4-6. When one reaches that point, that indeed is a "soul-damning fall from

grace." -- Al Maxey

From a Reader in California:

Love ya, brother, and am looking forward to your writings this new year! They bring fresh air to my spirit.

From a Reader in Unknown:

"Sad Saga of a Soused Sailor" was a very interesting study, Al, and a great handling of a difficult passage!

From a Reader in Korea:

Al, I ran across something on Facebook that has confused me a bit. Since you are a great scholar, you may already have done

some research on this topic. Would you expound on the meaning of "betrothed"? Sounds like "engaged" to me. But I've never heard a sermon

on how to live with your fiancée while you set the wedding date.

The Jewish concept of "betrothal," especially as it was understood and practiced among the Jews

during the time of Christ and before, is vastly different from the modern concept of an "engagement." One commentator wrote, "Betrothal in most

eras of Bible history involved two families in a formal contract, and that contract was as binding as marriage itself." Indeed, the word "divorce" was

used to indicate the breaking of this covenant/contract. If a woman were to become pregnant by another man during this time, the penalty for her

was death (see my article "The High Cost of Seduction" - Reflections

#812). This may help explain why Joseph, when he discovered Mary was pregnant, determined to "put her away" (divorce her) "secretly"

or "quietly." The consequences for Mary, otherwise, could have been severe. Although betrothals at that time were more legally binding than our

present-day engagements (at least in our culture), the couple nevertheless did not live together as husband and wife, nor did they engage in sexual

activity with one another, until after the wedding festivities, even though in the eyes of the Jewish community they were regarded as legally and

morally bound to one another. I deal with the Jewish concept of betrothal and marriage more fully in my following study: "In My

Father's House" (Reflections #267), especially as these concepts relate to

the church's present "betrothal" to her Bridegroom Jesus the Messiah. Paul wrote to the church in Corinth: "For I feel a divine jealousy for you, since

I betrothed you to one husband, to present you as a pure virgin to Christ" (2 Corinthians 11:2 - English Standard Version). --

Al Maxey

********************

If you would like to be added to or removed from this

mailing list, Contact Me and I'll immediately comply.

If you are challenged by these Reflections, then feel

free to send them on to others and encourage them

to write for a free subscription. These articles may

all be obtained on a special CD. Check the Archives

for details and all past issues of these Reflections at:

http://www.zianet.com/maxey/Reflect2.htm

Mankind, regardless of time, place, and culture, has always had a tendency to try and encapsulate its fundamental religious and spiritual beliefs

and convictions in brief forms easily remembered. These have been called creeds, confessions, and canons

of faith. The obvious shortcoming of any such creed, confession, or canon is that no single statement of belief will ever fully express the fulness

of faith of all mankind. Our understandings and convictions regarding our Creator and His will for His creation differ greatly from

person to person, nation to nation, and culture to culture. Thus, over the course of human history countless creeds have appeared. The

Oxford English Dictionary defines a "creed" (as it pertains to those who follow Jesus) as "a brief formal summary of the Christian faith."

Yet, it is quite clearly so much more, for in these statements "the element of personal trust in God is prominent. A creed is thus something more

than a symposium of accepted belief or even an epitome of divinely revealed truth. It involves the existential commitment of the confessor to God"

[The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 1, p. 805].

Mankind, regardless of time, place, and culture, has always had a tendency to try and encapsulate its fundamental religious and spiritual beliefs

and convictions in brief forms easily remembered. These have been called creeds, confessions, and canons

of faith. The obvious shortcoming of any such creed, confession, or canon is that no single statement of belief will ever fully express the fulness

of faith of all mankind. Our understandings and convictions regarding our Creator and His will for His creation differ greatly from

person to person, nation to nation, and culture to culture. Thus, over the course of human history countless creeds have appeared. The

Oxford English Dictionary defines a "creed" (as it pertains to those who follow Jesus) as "a brief formal summary of the Christian faith."

Yet, it is quite clearly so much more, for in these statements "the element of personal trust in God is prominent. A creed is thus something more

than a symposium of accepted belief or even an epitome of divinely revealed truth. It involves the existential commitment of the confessor to God"

[The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 1, p. 805].