The Giant Cities of Bashan and Syria’s Holy Places

Rev. J. L. Porter D. D.

LONDON: T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW;

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK

1877

Pages: 64 - 78IV.

BOZRAH.

"And judgment is come ... upon Bozrah." - Jer. 48:24.

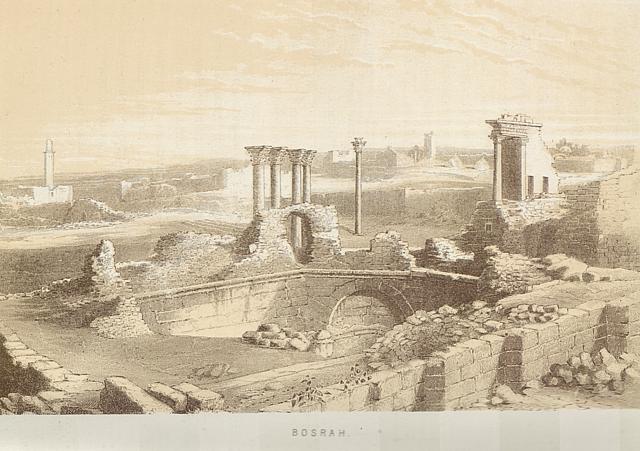

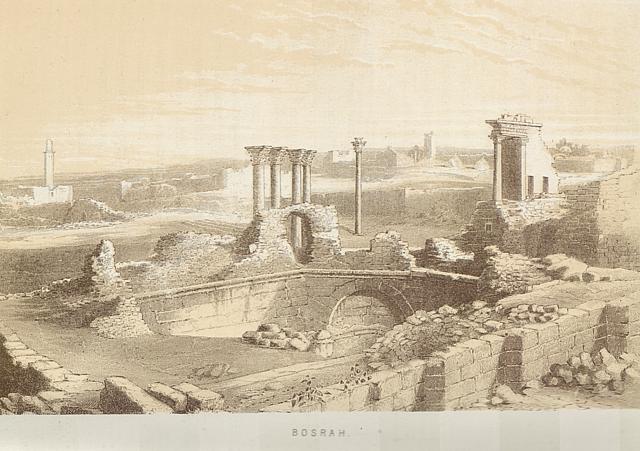

I spent three days at Bozrah. There is much to be

seen there, - much of Scriptural, and still more of historical and

antiquarian interest; and I tried to see it all. Bozrah was a strong

city, as its name implies - Bozrah, "fortress," - and a

magnificent city; and numerous vestiges of its ancient strength and

magnificence remain to this day. Its ruins are nearly five miles in

circuit; its walls are lofty and massive; and

its castle is one of the largest and strongest fortresses in Syria.

Among the ruins I saw two theatres, six temples, and ten or twelve

churches and mosques; besides palaces, baths, fountains, aqueducts,

triumphal arches, and other structures almost without number. The old

Bozrites must have been men of great taste and enterprise as well as

wealth. Some of the buildings I saw there would grace the proudest

capital of modern Europe.

It was a work of no little toil to explore

Bozrah. The streets are mostly covered, and in some places completely

blocked up, with fallen buildings and heaps of rubbish. Over these I

had to climb, risking my limbs among loose stones.

The principal structures, too, are so much encumbered with broken

columns and the piled-up ruins of roofs and pediments, that one has

great difficulty in getting at them, and discovering their points of

interest or beauty. In trying to copy a Greek inscription over the door

of a church, I clambered to the top of a wall. My weight caused it to

topple over, and it fell with a terrible crash. It was only by a sudden

and hazardous leap I escaped, and barely escaped, being buried beneath

it. And we were hourly exposed to danger of another and still more

pressing kind. Bozrah had once a population of a hundred thousand souls

and more; when I was there its whole inhabitants comprised just twenty families!

These live huddled together in the lower stories of some very ancient

houses near the castle. The rest of the city is completely desolate.

The fountains near the city, and the rich pastures which encircle them,

attract wandering BedawÓn, - outcasts from the larger tribes, and

notorious thieves and brigands. These come up from the desert with a

few goats, sheep, and donkeys, and perhaps a horse; and they lurk,

gipsy-like, about the fountains and among the ruins of the large

outlying towns of Bashan, watching every opportunity to plunder an unguarded caravan or strip

(Luke 10:30) an unwary traveller, or steal a stray camel. The whole

environs of Bozrah are infested with them, owing to the extent of the

ruins and the numbers of wells and springs in and around them. Our

arrival, numbers, and equipments had been carefully noted; and armed

men lay in wait, as we soon discovered, at various places, in the hope

of entrapping and plundering some straggler. Once, indeed, a bold

attempt was made by their combined forces to carry off our whole party.

We had fortunately taken the precaution on our arrival to engage the

brother of the sheikh as guide and guard during our stay; and to this

arrangement, joined to the fear of the Druse escort, we owed our

safety. So true has time made the words of Jeremiah: "The spoilers are come upon all high places through the wilderness ... no flesh shall have peace" (Jer. 12:12). The words of Ezekiel, too, are strikingly applicable to the present state of Bozrah: "Thus

saith the Lord God of the land of Israel, They shall eat their bread

with carefulness, and drink their water with astonishment, that her

land may be desolate from all that is therein, because of the violence

of all them that dwell therein. And the cities that are inhabited shall

be laid waste, and the land shall be desolate" (Ezek. 12:19, 20).

It was a work of no little toil to explore

Bozrah. The streets are mostly covered, and in some places completely

blocked up, with fallen buildings and heaps of rubbish. Over these I

had to climb, risking my limbs among loose stones.

The principal structures, too, are so much encumbered with broken

columns and the piled-up ruins of roofs and pediments, that one has

great difficulty in getting at them, and discovering their points of

interest or beauty. In trying to copy a Greek inscription over the door

of a church, I clambered to the top of a wall. My weight caused it to

topple over, and it fell with a terrible crash. It was only by a sudden

and hazardous leap I escaped, and barely escaped, being buried beneath

it. And we were hourly exposed to danger of another and still more

pressing kind. Bozrah had once a population of a hundred thousand souls

and more; when I was there its whole inhabitants comprised just twenty families!

These live huddled together in the lower stories of some very ancient

houses near the castle. The rest of the city is completely desolate.

The fountains near the city, and the rich pastures which encircle them,

attract wandering BedawÓn, - outcasts from the larger tribes, and

notorious thieves and brigands. These come up from the desert with a

few goats, sheep, and donkeys, and perhaps a horse; and they lurk,

gipsy-like, about the fountains and among the ruins of the large

outlying towns of Bashan, watching every opportunity to plunder an unguarded caravan or strip

(Luke 10:30) an unwary traveller, or steal a stray camel. The whole

environs of Bozrah are infested with them, owing to the extent of the

ruins and the numbers of wells and springs in and around them. Our

arrival, numbers, and equipments had been carefully noted; and armed

men lay in wait, as we soon discovered, at various places, in the hope

of entrapping and plundering some straggler. Once, indeed, a bold

attempt was made by their combined forces to carry off our whole party.

We had fortunately taken the precaution on our arrival to engage the

brother of the sheikh as guide and guard during our stay; and to this

arrangement, joined to the fear of the Druse escort, we owed our

safety. So true has time made the words of Jeremiah: "The spoilers are come upon all high places through the wilderness ... no flesh shall have peace" (Jer. 12:12). The words of Ezekiel, too, are strikingly applicable to the present state of Bozrah: "Thus

saith the Lord God of the land of Israel, They shall eat their bread

with carefulness, and drink their water with astonishment, that her

land may be desolate from all that is therein, because of the violence

of all them that dwell therein. And the cities that are inhabited shall

be laid waste, and the land shall be desolate" (Ezek. 12:19, 20).

The sheikh of Bozrah told me that his flocks would not be safe even in his own court-yard at night, and that armed sentinels had to patrol continually round their little fields at harvest-time. "If it were not for the castle," he said, "which has high walls, and a strong iron gate, we should be forced to leave Busrah altogether. We could not stay here a week. The BedawÓn swarm round the ruins. They steal everything they can lay hold of, - goat, sheep, cow, horse, or camel; and before we can get on their track they are far away in the desert."

Two or three incidents came under my own notice which proved the truth of the sheikh’s sad statement. One day when examining the ruins of a large mosque, the head of a Bedawy appeared over an adjoining wall, looking at us. The sheikh, who was by my side, cried out, on seeing him, "Dog, you stole my sheep!" and seizing a stone he hurled it at him with such force and precision as must have brained him had he not ducked behind the wall. The sheikh and his companions gave chase, but the fellow escaped. One cannot but compare such scenes, scenes of ordinary life, of everyday occurrence in Bashan, with the language of prophecy: "I will give it (the land of Israel) into the hands of the strangers for a prey, and to the wicked of the earth for a spoil; ... robbers shall enter into it and defile it ... The land is full of bloody crimes, and the city is full of violence" (Ezek. 7:2, 21-23).

Bozrah was one of the strongest cities of Bashan; it was, indeed, the most celebrated fortress east of the Jordan, during the Roman rule in Syria. Some parts of its wall are still almost perfect, a massive rampart of solid masonry, fifteen feet thick and nearly thirty high, with great square towers at intervals. The walled city was almost a rectangle, about a mile and a quarter long by a mile broad; and outside this were large straggling suburbs. A straight street intersects the city lengthwise, and has a beautiful gate at each end; and other straight streets run across it Roman Bozrah (or Bostra) was a beautiful city, with long straight avenues and spacious thoroughfares; but the Saracens built their miserable little shops and quaint irregular houses along the sides of the streets, out and in, here and there, as fancy or funds directed; and they thus converted the stately Roman capital, as they did Damascus and, Antioch, into a labyrinth of narrow, crooked, gloomy lanes. One sees the splendid, Roman palace, and gorgeous Greek temple, and shapeless Arab dukk‚n, side by side, alike in ruins, just as if the words of Isaiah had been written with special reference to this City of Moab: "He shall bring down their pride together with the spoil of their hands. And the fortress of the high fort of thy walls shall He bring down, lay low, and bring to the ground, even to the dust" (Isa. 15:11, 12).

It might perhaps be as trying to my reader’s patience as it was to my limbs, were I to retrace with him all my wanderings among the ruins of Bozrah; relating every little incident and adventure; and describing the wonders of art and architecture, and the curiosities of votive tablet, and dedicatory inscription on altar, tomb, church, and temple, which I examined and deciphered during these three days. Still I think many will wish to hear a few particulars about an old Bible city, and a city of so much historical importance in the latter days of Bashan’s glory. To me and to my companions it was intensely interesting to note the changes that old city has undergone. They are shown in the strata of its ruins just as geological periods are shown in the strata of the earth’s crust. Some of them are recorded, too, on monumental tablets, containing the legends of other centuries. In one spot, deep down beneath the accumulated remains of more recent buildings, I saw the simple, massive, primitive dwellings of the aborigines, with their stone doors and stone roofs. These were built and inhabited by the gigantic Emim and Rephaim long before the Chaldean shepherd migrated from Ur to Canaan (Gen. 14:5). High above them rose the classic portico of a Roman temple, shattered and tottering, but still grand in its ruins. Passing between the columns, I saw over its beautifully sculptured doorway a Greek inscription, telling how, in the fourth century, the temple became a church, and was dedicated to St. John. On entering the building, the record of still another change appeared on the cracked plaster of the walls. Upon it was traced in huge Arabic characters the well-known motto of Islamism: - "There is no God but God, and Mohammed is the prophet of God."

One of the first buildings I visited was the castle, and on my way to it I passed a triumphal arch, erected, as a Latin inscription tells us, in honour of Julius, prefect of the first Parthian Philippine legion. It was most likely built during the reign of the emperor Philip, who was a native of Bozrah. The castle stands on the south side of the city, without the walls; and forming a separate fortress, was fitted at once to defend and command the town. It is of great size and strength, and the outer walls, towers, gate, and moat are nearly perfect; but the interior is ruinous. On the basement are immense vaulted tanks, stores, and galleries; and over them were chambers sufficient to accommodate a small army. In the very centre of the structure, supported on massive piers and arches, are the remains of a theatre. This splendid monument of the luxury and magnificence of former days was so designed that the spectators commanded a view of the city and the whole plain beyond it to the base of Hermon. The building is a semicircle, 270 feet in diameter, and open above, like all Roman theatres. It was no doubt intended for the amusement of the Roman garrison, when Bostra was the capital of a province and the headquarters of a legion.*

The keep is a huge square tower, rising high above the battlements, and overlooking the plains of Bashan and Moab. From it I saw that Bozrah was in ancient times connected by a series of great highways with the leading cities and districts in Bashan and Arabia. They diverge from the city in straight lines; and my eye followed one after another till it disappeared in the far distance. One ran westward to the town of Ghusam, and then to Edrei; another northward to Suweideh and Damascus; another north-west, up among the mountains of Bashan; another to Kerioth; and another eastward, straight as an arrow, to the castle of Salcah, which crowned a conical hill on the horizon. Towns and villages appeared in every direction, thickly dotting the vast plain; a few of those to the north are inhabited, but all those southward have been deserted for centuries. I examined them long and carefully with my telescope, and their walls and houses appeared to be in even better preservation than those I had already visited. This has since been found to be the case, for my friend Mr. Cyril Graham visited them, penetrating this wild and dangerous country as far as Um el Jem‚l, the Beth-gamul of Scripture, which I saw from Bozrah, and to which I called his special attention. Beth-gamul is unquestionably one of the most remarkable places east of the Jordan. It is as large as Bozrah. It is surrounded by high walls, and contains many massive houses built of huge blocks of basalt; their roofs and doors, and even the gates of the city, being formed of the same material. Though deserted for many centuries, the houses, streets, walls, and gates are in as perfect preservation as if the city had been inhabited until within the last few years. It is curious to note the change that has taken place in the name. What the Hebrews called "The house of the camel," the Arabs now call "The mother of the camel."

I cannot tell how deeply I was impressed when looking out over that noble plain, rivalling in richness of soil the best of England’s counties, thickly studded with cities, towns, and villages, intersected with roads, having one of the finest climates in the world; and yet utterly deserted, literally "without man, without inhabitant, and without beast" (Isa. 33:10). I cannot tell with what mingled feelings of sorrow and of joy, of mourning and of thanksgiving, of fear and of faith, I reflected on the history of that land; and taking out my Bible compared its existing state, as seen with my own eyes, with the numerous predictions regarding it written by the Hebrew prophets. In their day it was populous and prosperous; the fields-waved with corn; the hill-sides were covered with flocks and herds; the highways were thronged with wayfarers; the cities resounded with the continuous din of a busy population. And yet they wrote as if they had seen the land as I saw it from the ramparts of Bozrah. The Spirit of the omniscient God alone could have guided the hand that penned such predictions as these: "Then said I, Lord, how long? And he answered, Until the cities be wasted without inhabitant, and the houses without man, and the land be utterly desolate, and the Lord hath removed men far away, and there be a great forsaking in the midst of the land" (Isa. 6:11, 12). "The destroyer of the Gentiles is on his way; he is gone forth from his place to make thy land desolate; and thy cities shall be laid waste without an inhabitant" (Jer. 4:7).

In former times a garrison was maintained in the castle of Bozrah by the Pasha of Damascus, for the purpose of defending the southern sections of Bashan from the periodical incursions of the BedawÓn. It has been withdrawn for many years. The "Destroyer of the Gentiles" can now come up unrestrained, "the spoilers" can now "come upon all high places through the wilderness," the sword now" devours from the one end of the land even to the other end of the land" (Jer. 12:12); the cities are "without inhabitant," the houses are "without man," the land is "utterly desolate," judgment has come upon it all far and near; in a word, THE WHOLE OF BASHAN AND MOAB IS ONE GREAT FULFILLED PROPHECY.

We were conducted by our intelligent guide to a large church, apparently the ancient cathedral of Bozrah. It is built in the form of a Greek cross, and on the walls of the chancel are some remains of rude frescos, representing saints and angels. Over the door is an inscription stating that the church was founded "by Julianus, archbishop of Bostra, in the year A.D. 513, in honour of the blessed martyrs Sergius, Bacchus, and Leontius." Our guide called the building "the church of the monk Bohira;" and a very old tradition represents this monk as playing an important part in the early history of Mohammedanism. It is said he was a native of this city, and that, being expelled from his convent, he joined the Arabian prophet, and aided in writing the Koran, supplying all those stories from the Bible, the Talmud, and the spurious Gospels, which make up so large a part of that remarkable book.

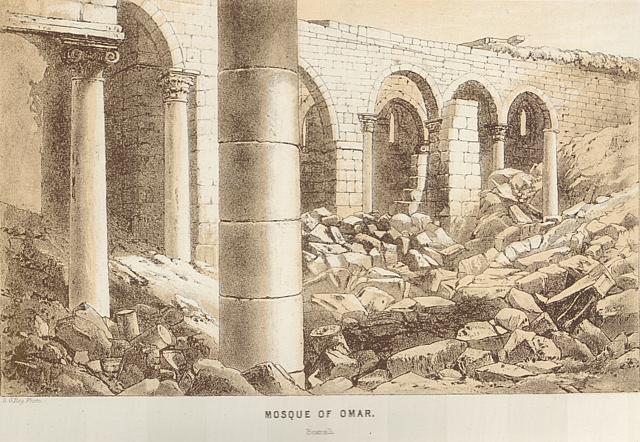

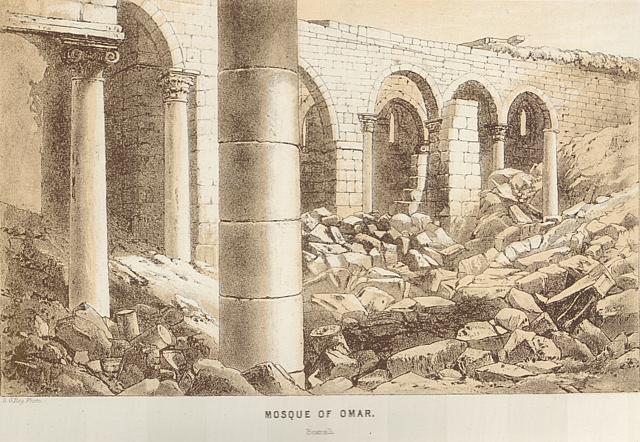

Not far from the church is the principal mosque, built, it is said, by the Khalif Omar. The roof was supported on colonnades, like the early basilicas; and seventeen of the columns are monoliths of white marble, of great beauty. Two of them have inscriptions showing that they formerly belonged to some church, but probably they were originally intended to ornament a Greek temple.

We extended our walk one day to the suburbs on the north and west, where there are remains of some large and splendid buildings. We then proceeded to the west gate, at the end of the main street. The ancient pavement of the street, and of the road which runs across the plain to Ghusam, is quite perfect, - not a stone out of place. The gate has a single but spacious Roman arch, ornamented with pilasters and niches. Outside is a guard-house of the same style and period. Sitting down on the broken wall of this little building, I gazed long on the ruins of the city, and on the vast deserted plain. My companions had taken shelter from a shower in a vacant niche; and now there was not a human being, there was not a sign of life, within the range of vision. The open gate revealed heaps of rubbish, and piles of stones, and shattered walls. In the distance a solitary column stood here. and there, and the triumphal arch which rose over all around it, appeared as if built to celebrate the triumph of DESOLATION. The desolation of the plain without was as complete as that of the city within. Never before had I seen such a picture of utter, terrible desolation, except at Palmyra; and even there it was not so remarkable. That "city of the desert" might rise and flourish for a season, while the tide of commerce was rolling past it, and while it stood a solitary oasis on the desert highway uniting the eastern and western worlds; but on the opening up of some other channel of communication, it might naturally decline and fall. Bozrah is altogether different. It was situated in the midst of a fertile plain, in the centre of a populous province. It had abundant resources, fountains of water, an impregnable fortress. Why should Bozrah become desolate? Who would have ventured to predict its ruin 1 It surely was no city to grow up in a day and fade in a night! It surely did not depend for prosperity on the changeable channel of commerce! Something above and beyond mere natural causes and influences must have operated here. We can only understand its strange history when we read it in the light of prophecy. Then we can see the impress of a mightier than: human hand. We can see that the curse of an angry God for the sin of a rebellious people has fallen upon Bozrah, "and upon all the cities of the land of Moab far and near" (Jer. 48:24).

Two Bozrahs are mentioned in the Bible. One was

in Edom, and is referred to in the well-known passage, "Who is this

that cometh from Edom, with dyed garments from Bozrah?" (Isa.

63:1). Upon this ancient city judgments are pronounced in connection

with Edom and Teman, whose inhabitants dwelt "in the clefts of the

rocks," and the "heights of the hills," and made their houses "like the

nests of the eagles" (Jer. 49:7-22.) When pronouncing judgment upon Moab, the same prophet says, "Judgment is come upon the plain country," and he names the cities which stood in the plain, and among them are Beth-gamul, Kerioth, and Bozrah

(Jer. 48:21-24). Evidently these predictions cannot refer to the same

place. Another fact still more conclusively establishes the point.

After completing the sentence of Moab, including one Bozrah, the Spirit of God adds, "Yet will I bring again the captivity of Moab

in the latter days" (Jer. 48:47); whereas in Edom’s doom we have these

terrible words, "For I have sworn by myself, saith the Lord, that

Bozrah shall become a desolation, a reproach, a waste, and a curse; and

all the cities thereof shall be perpetual wastes" (Jer. 49:13).**

Two Bozrahs are mentioned in the Bible. One was

in Edom, and is referred to in the well-known passage, "Who is this

that cometh from Edom, with dyed garments from Bozrah?" (Isa.

63:1). Upon this ancient city judgments are pronounced in connection

with Edom and Teman, whose inhabitants dwelt "in the clefts of the

rocks," and the "heights of the hills," and made their houses "like the

nests of the eagles" (Jer. 49:7-22.) When pronouncing judgment upon Moab, the same prophet says, "Judgment is come upon the plain country," and he names the cities which stood in the plain, and among them are Beth-gamul, Kerioth, and Bozrah

(Jer. 48:21-24). Evidently these predictions cannot refer to the same

place. Another fact still more conclusively establishes the point.

After completing the sentence of Moab, including one Bozrah, the Spirit of God adds, "Yet will I bring again the captivity of Moab

in the latter days" (Jer. 48:47); whereas in Edom’s doom we have these

terrible words, "For I have sworn by myself, saith the Lord, that

Bozrah shall become a desolation, a reproach, a waste, and a curse; and

all the cities thereof shall be perpetual wastes" (Jer. 49:13).**

The plain of Moab embraced a large part of the plateau east of the Dead Sea and the Jordan. A short time before the exodus the Amorites conquered the northern part of that plain; and from them it was taken by the tribes of Reuben and Gad. It is doubtful whether the Moabites were ever completely expelled. They probably retired for a time to the desert, and when Israel’s power declined, returned to their old possessions. The predictions of Jeremiah refer to cities once held by the Israelites, yet in his days belonging to Moab; hence he includes Bozrah in the land of Moab. Subsequently, Bozrah became the capital of a large Roman province; then the metropolitan city of Eastern Palestine, when its primate had thirty-three bishops under him; then it was captured by the Mohammedans, and gradually fell to ruin. Now we can see that the prophet’s words are fulfilled, "Judgment has come upon Bozrah."

We had not gone more than four miles from Bozrah when an alarm was raised. The people of Bozrah had told us, and we had known ourselves, that though the country on our proposed route is thickly studded with towns and villages, yet not a single human being dwells in them. When approaching the village of Burd we saw figures moving about. At first we thought some shepherds had taken refuge there. with their flocks; but it very soon became apparent that the figures were not shepherds. Considerable numbers collected on the flat house-tops, and we could see horses led out and held beneath the walls. They evidently saw us, and were preparing for an attack. We held a council of war, - and resolved unanimously to go forward, and if attacked to meet the enemy, boldly. Mahmood, after examining his gun and pistols, and loosening his sword in its seaboard, galloped off to reconnoiter. A horseman came out to meet him. I confess it was rather an anxious moment, but it did not last long. A few words were spoken, and Mahmood came back with the welcome intelligence that a little colony of Druses had migrated to the village two days previously. They were as much alarmed at us as we were at them. So it is always now in this unfortunate land, where the Ishmaelite roams free - "His hand against every man and every man’s hand against him." Every stranger is looked upon as an enemy until he is proved to be a friend. The time and events so graphically depicted by Jeremiah have come: "O inhabitant of Aroer, stand by the way and espy: ask him that fleeth, and her that escapeth, and say, What is done?" (Jer. 48:19)

We rode on along the Roman road, stopping occasionally to examine with our glasses the deserted towns away to the right and left, and once or twice galloping to those near the road, so as to inspect their strange massive houses, standing complete, but tenantless. Often and often did our eyes sweep the open plain, and scan suspicious ruins, and peer into valleys, in the fear or hope of discovering roving Ishmaelites. We were almost disappointed that none appeared.

Soon after leaving Burd, we entered a rocky district; and here, among the rocks, we found some fields where a few Druses were ploughing, each man having his gun slung over his shoulders, and pistols in his belt. This is surely cultivation under difficulties. From this place until we reached Salcah, we did not see a living creature, except a flock of partridges and a herd of gazelles. The desert of Arabia is not more desolate than this rich and once populous plain of Moab.

Salcah is one of the most remarkable cities in Palestine. It has been long deserted; and yet, as nearly as I could estimate, five hundred of its houses are still standing, and from three to four hundred families might settle in it at any moment without laying a stone, or expending an hour’s labour on repairs. The circumference of the town and castle together is about three miles. Besides the castle, a number of square towers, like the belfries of churches, and a few mosques, appear to be the only public buildings.

On approaching Salcah, we rode through an old cemetery, and then, passing the ruins of an ancient gate, entered the streets of the deserted city. The open doors, the empty houses, the rank grass and weeds, the long straggling brambles in the door-ways and windows, formed a strange, impressive picture which can never leave my memory. Street after street we traversed, the tread of our horses awakening mournful echoes, and startling the foxes from their dens in the palaces of Salcah. Reaching an open paved area, in front of the principal mosque, we committed our horses to the keeping of Mahmood, who tied them up, unstrung his gun, and sat down to act the part of sentry, while we explored the city.

The castle occupies the summit of a steep conical hill, which rises to the height of some three hundred feet, and is the southern point of the mountain range of Bashan. Round the base of the hill is a deep moat, and, another still deeper encircles the walls of the fortress. The building is a patch-work of various periods and nations. The foundations are Jewish, if not earlier; Roman rustic masonry appears above them; and over all is lighter Saracenic work, with beautifully interlaced inscriptions. The exterior walls are not much defaced, but the interior is one confused mass of ruins.

The view from the top is wide and wonderfully interesting. It embraces the whole southern slopes of the mountains, which, though rocky, are covered from bottom to top with artificial terraces, and fields divided by stone fences. From their base the plain of Bashan stretches out on the west to Hermon; the plain of Moab on the south, to the horizon; and the plain of Arabia on the east, beyond the range of vision. For more than an hour I sat gazing on that vast panorama. Wherever I turned my eyes towns and villages were seen. Bozrah was there on its plain, twelve miles distant. The towers of Beth-gamul were faintly visible far away on the horizon. In the vale immediately to the south of Salcah are several deserted towns, whose names I could not ascertain. Three miles off, in the same direction, is a hill called Abd el-Maaz, with a large deserted town on its eastern side. To the south-east an ancient road runs straight across the plain far as the eye can see. About six miles along it, on the top of a hill, is the deserted town of Maleh. On the section of the plain between south and east I counted fourteen towns, all of them, so far as I could see with my telescope, habitable like Salcah, but entirely deserted! From this one spot I saw upwards of thirty deserted towns! Well might I exclaim with the prophet, as I sat on the ruins of this great fortress, and looked over that mournful scene of utter desolation, "Moab is spoiled, and gone up out if her cities ... Moab is confounded; for it is broken down: howl and cry; tell ye it in Arnon that Moab is spoiled, and judgment is come upon the plain country ... Upon Kiriathaim, and upon Beth-gamul, and upon Beth-meon, and upon Kerioth, upon Bozrah, and upon all the cities of the land of Moab, far and near" (Jer. 48:15-24).

Another feature of the landscape impressed me still more deeply. Not only is the country-plain and hill-side alike - chequered with fenced fields, but groves of fig-trees are here and there seen, and terraced vineyards still clothe the sides of some of the hills. These are neglected and wild, but not fruitless. Mahmood told us that they produce great quantities of figs and grapes, which are rifled year after year by the BedawÓn in their periodical raids. How literal and how true have the words of Jeremiah become! "O vine if Sibmah, I will weep for thee with the weeping of Jazer: ... the spoiler is fallen upon thy summer fruits, and upon thy vintage. And joy and gladness is taken from the plentiful field, and from the land of Moab; and I have caused wine to fail from the wine-presses; none shall tread with shouting" (Jer. 48:32, 33). Nowhere on earth is there such a melancholy example of tyranny, rapacity, and misrule, as here. Fields, pastures, vineyards, houses, villages, cities - all alike deserted and waste. Even the few inhabitants that have hid themselves among the rocky fastnesses and mountain defiles drag out a miserable existence, oppressed by robbers of the desert on the one hand, and robbers of the government on the other. It would seem as if the people of Moab had heard the injunction of Jeremiah: "O ye that dwell in Moab, leave the cities and dwell in the rock, and be like the dove that maketh her nest in the side of the hole’s mouth." And even thus they cannot escape, for "He that fleeth shall fall into the pit; and he that getteth up out of the pit shall be taken in the snare: for I will bring upon it, even upon Moab, the year of their visitation, saith the Lord" (Jer. 48:28, 44).

The sheikh of Bozrah told me that his flocks would not be safe even in his own court-yard at night, and that armed sentinels had to patrol continually round their little fields at harvest-time. "If it were not for the castle," he said, "which has high walls, and a strong iron gate, we should be forced to leave Busrah altogether. We could not stay here a week. The BedawÓn swarm round the ruins. They steal everything they can lay hold of, - goat, sheep, cow, horse, or camel; and before we can get on their track they are far away in the desert."

Two or three incidents came under my own notice which proved the truth of the sheikh’s sad statement. One day when examining the ruins of a large mosque, the head of a Bedawy appeared over an adjoining wall, looking at us. The sheikh, who was by my side, cried out, on seeing him, "Dog, you stole my sheep!" and seizing a stone he hurled it at him with such force and precision as must have brained him had he not ducked behind the wall. The sheikh and his companions gave chase, but the fellow escaped. One cannot but compare such scenes, scenes of ordinary life, of everyday occurrence in Bashan, with the language of prophecy: "I will give it (the land of Israel) into the hands of the strangers for a prey, and to the wicked of the earth for a spoil; ... robbers shall enter into it and defile it ... The land is full of bloody crimes, and the city is full of violence" (Ezek. 7:2, 21-23).

Bozrah was one of the strongest cities of Bashan; it was, indeed, the most celebrated fortress east of the Jordan, during the Roman rule in Syria. Some parts of its wall are still almost perfect, a massive rampart of solid masonry, fifteen feet thick and nearly thirty high, with great square towers at intervals. The walled city was almost a rectangle, about a mile and a quarter long by a mile broad; and outside this were large straggling suburbs. A straight street intersects the city lengthwise, and has a beautiful gate at each end; and other straight streets run across it Roman Bozrah (or Bostra) was a beautiful city, with long straight avenues and spacious thoroughfares; but the Saracens built their miserable little shops and quaint irregular houses along the sides of the streets, out and in, here and there, as fancy or funds directed; and they thus converted the stately Roman capital, as they did Damascus and, Antioch, into a labyrinth of narrow, crooked, gloomy lanes. One sees the splendid, Roman palace, and gorgeous Greek temple, and shapeless Arab dukk‚n, side by side, alike in ruins, just as if the words of Isaiah had been written with special reference to this City of Moab: "He shall bring down their pride together with the spoil of their hands. And the fortress of the high fort of thy walls shall He bring down, lay low, and bring to the ground, even to the dust" (Isa. 15:11, 12).

It might perhaps be as trying to my reader’s patience as it was to my limbs, were I to retrace with him all my wanderings among the ruins of Bozrah; relating every little incident and adventure; and describing the wonders of art and architecture, and the curiosities of votive tablet, and dedicatory inscription on altar, tomb, church, and temple, which I examined and deciphered during these three days. Still I think many will wish to hear a few particulars about an old Bible city, and a city of so much historical importance in the latter days of Bashan’s glory. To me and to my companions it was intensely interesting to note the changes that old city has undergone. They are shown in the strata of its ruins just as geological periods are shown in the strata of the earth’s crust. Some of them are recorded, too, on monumental tablets, containing the legends of other centuries. In one spot, deep down beneath the accumulated remains of more recent buildings, I saw the simple, massive, primitive dwellings of the aborigines, with their stone doors and stone roofs. These were built and inhabited by the gigantic Emim and Rephaim long before the Chaldean shepherd migrated from Ur to Canaan (Gen. 14:5). High above them rose the classic portico of a Roman temple, shattered and tottering, but still grand in its ruins. Passing between the columns, I saw over its beautifully sculptured doorway a Greek inscription, telling how, in the fourth century, the temple became a church, and was dedicated to St. John. On entering the building, the record of still another change appeared on the cracked plaster of the walls. Upon it was traced in huge Arabic characters the well-known motto of Islamism: - "There is no God but God, and Mohammed is the prophet of God."

One of the first buildings I visited was the castle, and on my way to it I passed a triumphal arch, erected, as a Latin inscription tells us, in honour of Julius, prefect of the first Parthian Philippine legion. It was most likely built during the reign of the emperor Philip, who was a native of Bozrah. The castle stands on the south side of the city, without the walls; and forming a separate fortress, was fitted at once to defend and command the town. It is of great size and strength, and the outer walls, towers, gate, and moat are nearly perfect; but the interior is ruinous. On the basement are immense vaulted tanks, stores, and galleries; and over them were chambers sufficient to accommodate a small army. In the very centre of the structure, supported on massive piers and arches, are the remains of a theatre. This splendid monument of the luxury and magnificence of former days was so designed that the spectators commanded a view of the city and the whole plain beyond it to the base of Hermon. The building is a semicircle, 270 feet in diameter, and open above, like all Roman theatres. It was no doubt intended for the amusement of the Roman garrison, when Bostra was the capital of a province and the headquarters of a legion.*

The keep is a huge square tower, rising high above the battlements, and overlooking the plains of Bashan and Moab. From it I saw that Bozrah was in ancient times connected by a series of great highways with the leading cities and districts in Bashan and Arabia. They diverge from the city in straight lines; and my eye followed one after another till it disappeared in the far distance. One ran westward to the town of Ghusam, and then to Edrei; another northward to Suweideh and Damascus; another north-west, up among the mountains of Bashan; another to Kerioth; and another eastward, straight as an arrow, to the castle of Salcah, which crowned a conical hill on the horizon. Towns and villages appeared in every direction, thickly dotting the vast plain; a few of those to the north are inhabited, but all those southward have been deserted for centuries. I examined them long and carefully with my telescope, and their walls and houses appeared to be in even better preservation than those I had already visited. This has since been found to be the case, for my friend Mr. Cyril Graham visited them, penetrating this wild and dangerous country as far as Um el Jem‚l, the Beth-gamul of Scripture, which I saw from Bozrah, and to which I called his special attention. Beth-gamul is unquestionably one of the most remarkable places east of the Jordan. It is as large as Bozrah. It is surrounded by high walls, and contains many massive houses built of huge blocks of basalt; their roofs and doors, and even the gates of the city, being formed of the same material. Though deserted for many centuries, the houses, streets, walls, and gates are in as perfect preservation as if the city had been inhabited until within the last few years. It is curious to note the change that has taken place in the name. What the Hebrews called "The house of the camel," the Arabs now call "The mother of the camel."

I cannot tell how deeply I was impressed when looking out over that noble plain, rivalling in richness of soil the best of England’s counties, thickly studded with cities, towns, and villages, intersected with roads, having one of the finest climates in the world; and yet utterly deserted, literally "without man, without inhabitant, and without beast" (Isa. 33:10). I cannot tell with what mingled feelings of sorrow and of joy, of mourning and of thanksgiving, of fear and of faith, I reflected on the history of that land; and taking out my Bible compared its existing state, as seen with my own eyes, with the numerous predictions regarding it written by the Hebrew prophets. In their day it was populous and prosperous; the fields-waved with corn; the hill-sides were covered with flocks and herds; the highways were thronged with wayfarers; the cities resounded with the continuous din of a busy population. And yet they wrote as if they had seen the land as I saw it from the ramparts of Bozrah. The Spirit of the omniscient God alone could have guided the hand that penned such predictions as these: "Then said I, Lord, how long? And he answered, Until the cities be wasted without inhabitant, and the houses without man, and the land be utterly desolate, and the Lord hath removed men far away, and there be a great forsaking in the midst of the land" (Isa. 6:11, 12). "The destroyer of the Gentiles is on his way; he is gone forth from his place to make thy land desolate; and thy cities shall be laid waste without an inhabitant" (Jer. 4:7).

In former times a garrison was maintained in the castle of Bozrah by the Pasha of Damascus, for the purpose of defending the southern sections of Bashan from the periodical incursions of the BedawÓn. It has been withdrawn for many years. The "Destroyer of the Gentiles" can now come up unrestrained, "the spoilers" can now "come upon all high places through the wilderness," the sword now" devours from the one end of the land even to the other end of the land" (Jer. 12:12); the cities are "without inhabitant," the houses are "without man," the land is "utterly desolate," judgment has come upon it all far and near; in a word, THE WHOLE OF BASHAN AND MOAB IS ONE GREAT FULFILLED PROPHECY.

We were conducted by our intelligent guide to a large church, apparently the ancient cathedral of Bozrah. It is built in the form of a Greek cross, and on the walls of the chancel are some remains of rude frescos, representing saints and angels. Over the door is an inscription stating that the church was founded "by Julianus, archbishop of Bostra, in the year A.D. 513, in honour of the blessed martyrs Sergius, Bacchus, and Leontius." Our guide called the building "the church of the monk Bohira;" and a very old tradition represents this monk as playing an important part in the early history of Mohammedanism. It is said he was a native of this city, and that, being expelled from his convent, he joined the Arabian prophet, and aided in writing the Koran, supplying all those stories from the Bible, the Talmud, and the spurious Gospels, which make up so large a part of that remarkable book.

Not far from the church is the principal mosque, built, it is said, by the Khalif Omar. The roof was supported on colonnades, like the early basilicas; and seventeen of the columns are monoliths of white marble, of great beauty. Two of them have inscriptions showing that they formerly belonged to some church, but probably they were originally intended to ornament a Greek temple.

We extended our walk one day to the suburbs on the north and west, where there are remains of some large and splendid buildings. We then proceeded to the west gate, at the end of the main street. The ancient pavement of the street, and of the road which runs across the plain to Ghusam, is quite perfect, - not a stone out of place. The gate has a single but spacious Roman arch, ornamented with pilasters and niches. Outside is a guard-house of the same style and period. Sitting down on the broken wall of this little building, I gazed long on the ruins of the city, and on the vast deserted plain. My companions had taken shelter from a shower in a vacant niche; and now there was not a human being, there was not a sign of life, within the range of vision. The open gate revealed heaps of rubbish, and piles of stones, and shattered walls. In the distance a solitary column stood here. and there, and the triumphal arch which rose over all around it, appeared as if built to celebrate the triumph of DESOLATION. The desolation of the plain without was as complete as that of the city within. Never before had I seen such a picture of utter, terrible desolation, except at Palmyra; and even there it was not so remarkable. That "city of the desert" might rise and flourish for a season, while the tide of commerce was rolling past it, and while it stood a solitary oasis on the desert highway uniting the eastern and western worlds; but on the opening up of some other channel of communication, it might naturally decline and fall. Bozrah is altogether different. It was situated in the midst of a fertile plain, in the centre of a populous province. It had abundant resources, fountains of water, an impregnable fortress. Why should Bozrah become desolate? Who would have ventured to predict its ruin 1 It surely was no city to grow up in a day and fade in a night! It surely did not depend for prosperity on the changeable channel of commerce! Something above and beyond mere natural causes and influences must have operated here. We can only understand its strange history when we read it in the light of prophecy. Then we can see the impress of a mightier than: human hand. We can see that the curse of an angry God for the sin of a rebellious people has fallen upon Bozrah, "and upon all the cities of the land of Moab far and near" (Jer. 48:24).

The plain of Moab embraced a large part of the plateau east of the Dead Sea and the Jordan. A short time before the exodus the Amorites conquered the northern part of that plain; and from them it was taken by the tribes of Reuben and Gad. It is doubtful whether the Moabites were ever completely expelled. They probably retired for a time to the desert, and when Israel’s power declined, returned to their old possessions. The predictions of Jeremiah refer to cities once held by the Israelites, yet in his days belonging to Moab; hence he includes Bozrah in the land of Moab. Subsequently, Bozrah became the capital of a large Roman province; then the metropolitan city of Eastern Palestine, when its primate had thirty-three bishops under him; then it was captured by the Mohammedans, and gradually fell to ruin. Now we can see that the prophet’s words are fulfilled, "Judgment has come upon Bozrah."

We had not gone more than four miles from Bozrah when an alarm was raised. The people of Bozrah had told us, and we had known ourselves, that though the country on our proposed route is thickly studded with towns and villages, yet not a single human being dwells in them. When approaching the village of Burd we saw figures moving about. At first we thought some shepherds had taken refuge there. with their flocks; but it very soon became apparent that the figures were not shepherds. Considerable numbers collected on the flat house-tops, and we could see horses led out and held beneath the walls. They evidently saw us, and were preparing for an attack. We held a council of war, - and resolved unanimously to go forward, and if attacked to meet the enemy, boldly. Mahmood, after examining his gun and pistols, and loosening his sword in its seaboard, galloped off to reconnoiter. A horseman came out to meet him. I confess it was rather an anxious moment, but it did not last long. A few words were spoken, and Mahmood came back with the welcome intelligence that a little colony of Druses had migrated to the village two days previously. They were as much alarmed at us as we were at them. So it is always now in this unfortunate land, where the Ishmaelite roams free - "His hand against every man and every man’s hand against him." Every stranger is looked upon as an enemy until he is proved to be a friend. The time and events so graphically depicted by Jeremiah have come: "O inhabitant of Aroer, stand by the way and espy: ask him that fleeth, and her that escapeth, and say, What is done?" (Jer. 48:19)

We rode on along the Roman road, stopping occasionally to examine with our glasses the deserted towns away to the right and left, and once or twice galloping to those near the road, so as to inspect their strange massive houses, standing complete, but tenantless. Often and often did our eyes sweep the open plain, and scan suspicious ruins, and peer into valleys, in the fear or hope of discovering roving Ishmaelites. We were almost disappointed that none appeared.

Soon after leaving Burd, we entered a rocky district; and here, among the rocks, we found some fields where a few Druses were ploughing, each man having his gun slung over his shoulders, and pistols in his belt. This is surely cultivation under difficulties. From this place until we reached Salcah, we did not see a living creature, except a flock of partridges and a herd of gazelles. The desert of Arabia is not more desolate than this rich and once populous plain of Moab.

SALCAH.

Joshua tells us that the kingdom of Og the giant included "all Bashan unto Salcah" (Josh. 13:11, 12); and the Israelites took and occupied the whole region from Mount Hermon "unto Salcah." Salcah, the eastern frontier city of Bashan, was now before me; its great old castle perched on the top of a conical hill, overlooking a boundless plain, and the city itself spread along its sloping sides, and reaching out into the valley below. I felt glad and thankful that I was privileged to reach the utmost eastern border of Palestine. I had previously explored its northern border away on the plain of Hamath and on the heights of Lebanon, and its western border from Tripoli to Joppa; and since that time I have traversed the southern border from Gaza eastward.Salcah is one of the most remarkable cities in Palestine. It has been long deserted; and yet, as nearly as I could estimate, five hundred of its houses are still standing, and from three to four hundred families might settle in it at any moment without laying a stone, or expending an hour’s labour on repairs. The circumference of the town and castle together is about three miles. Besides the castle, a number of square towers, like the belfries of churches, and a few mosques, appear to be the only public buildings.

On approaching Salcah, we rode through an old cemetery, and then, passing the ruins of an ancient gate, entered the streets of the deserted city. The open doors, the empty houses, the rank grass and weeds, the long straggling brambles in the door-ways and windows, formed a strange, impressive picture which can never leave my memory. Street after street we traversed, the tread of our horses awakening mournful echoes, and startling the foxes from their dens in the palaces of Salcah. Reaching an open paved area, in front of the principal mosque, we committed our horses to the keeping of Mahmood, who tied them up, unstrung his gun, and sat down to act the part of sentry, while we explored the city.

The castle occupies the summit of a steep conical hill, which rises to the height of some three hundred feet, and is the southern point of the mountain range of Bashan. Round the base of the hill is a deep moat, and, another still deeper encircles the walls of the fortress. The building is a patch-work of various periods and nations. The foundations are Jewish, if not earlier; Roman rustic masonry appears above them; and over all is lighter Saracenic work, with beautifully interlaced inscriptions. The exterior walls are not much defaced, but the interior is one confused mass of ruins.

The view from the top is wide and wonderfully interesting. It embraces the whole southern slopes of the mountains, which, though rocky, are covered from bottom to top with artificial terraces, and fields divided by stone fences. From their base the plain of Bashan stretches out on the west to Hermon; the plain of Moab on the south, to the horizon; and the plain of Arabia on the east, beyond the range of vision. For more than an hour I sat gazing on that vast panorama. Wherever I turned my eyes towns and villages were seen. Bozrah was there on its plain, twelve miles distant. The towers of Beth-gamul were faintly visible far away on the horizon. In the vale immediately to the south of Salcah are several deserted towns, whose names I could not ascertain. Three miles off, in the same direction, is a hill called Abd el-Maaz, with a large deserted town on its eastern side. To the south-east an ancient road runs straight across the plain far as the eye can see. About six miles along it, on the top of a hill, is the deserted town of Maleh. On the section of the plain between south and east I counted fourteen towns, all of them, so far as I could see with my telescope, habitable like Salcah, but entirely deserted! From this one spot I saw upwards of thirty deserted towns! Well might I exclaim with the prophet, as I sat on the ruins of this great fortress, and looked over that mournful scene of utter desolation, "Moab is spoiled, and gone up out if her cities ... Moab is confounded; for it is broken down: howl and cry; tell ye it in Arnon that Moab is spoiled, and judgment is come upon the plain country ... Upon Kiriathaim, and upon Beth-gamul, and upon Beth-meon, and upon Kerioth, upon Bozrah, and upon all the cities of the land of Moab, far and near" (Jer. 48:15-24).

Another feature of the landscape impressed me still more deeply. Not only is the country-plain and hill-side alike - chequered with fenced fields, but groves of fig-trees are here and there seen, and terraced vineyards still clothe the sides of some of the hills. These are neglected and wild, but not fruitless. Mahmood told us that they produce great quantities of figs and grapes, which are rifled year after year by the BedawÓn in their periodical raids. How literal and how true have the words of Jeremiah become! "O vine if Sibmah, I will weep for thee with the weeping of Jazer: ... the spoiler is fallen upon thy summer fruits, and upon thy vintage. And joy and gladness is taken from the plentiful field, and from the land of Moab; and I have caused wine to fail from the wine-presses; none shall tread with shouting" (Jer. 48:32, 33). Nowhere on earth is there such a melancholy example of tyranny, rapacity, and misrule, as here. Fields, pastures, vineyards, houses, villages, cities - all alike deserted and waste. Even the few inhabitants that have hid themselves among the rocky fastnesses and mountain defiles drag out a miserable existence, oppressed by robbers of the desert on the one hand, and robbers of the government on the other. It would seem as if the people of Moab had heard the injunction of Jeremiah: "O ye that dwell in Moab, leave the cities and dwell in the rock, and be like the dove that maketh her nest in the side of the hole’s mouth." And even thus they cannot escape, for "He that fleeth shall fall into the pit; and he that getteth up out of the pit shall be taken in the snare: for I will bring upon it, even upon Moab, the year of their visitation, saith the Lord" (Jer. 48:28, 44).

*Modern research in this, as in many other cases, has confirmed the accuracy of Biblical topography. The Bozrah of Edom has been identified with the village of Buseireh, among the mountains north of Petra; and here, in the plain, we have the Bozrah of Moab. I was somewhat surprised recently to find that the writer of the article BOZRAH, in "Fairbairn’s Dictionary of the Bible," charges me with holding the opinion of Kitto and others, that Bozrah of Edom, Bozrah of Moab, and modern Busrah, are identical. I never held such an opinion. I have always affirmed, that Bozrah of Edom and Bozrah of Moab were distinct cities; and had the writer of the article mentioned turned to my "Five Years in Damascus," vol. 2 p. 160, or to my "Handbook," or to the article BOZRAH in the last edition of "Kitto’s Cyclopedia," he would have seen this.

**This opinion has been questioned by M. Rey, an accomplished French savant, who in the year 1858 retraced my footsteps through Bashan, and reviewed my "Five Years in Damascus" as he went along. I had the pleasure of meeting M. Rey on several occasions, and was impressed alike with his gentlemanly deportment and accomplished scholarship; but being an intimate friend of M. De Saulcy, whose pretended discoveries in and around Damascus I had criticized perhaps a little too severely, I am not surprised that he should make an occasional attempt at retaliation.

The Giant Cities of Bashan V